Baby names from the 30s: Most popular baby names in 1930 for boys and girls

Posted on50 Unique Baby Names You’ve Never Heard Of

Looking down the list, there’s a very good chance that you’ve never heard of most of these names. They are definitely unique, but not absurd. Plus, there’s a mix of names for boys and girls, but also plenty of gender-neutral names as well.

Updated: January 8, 2023

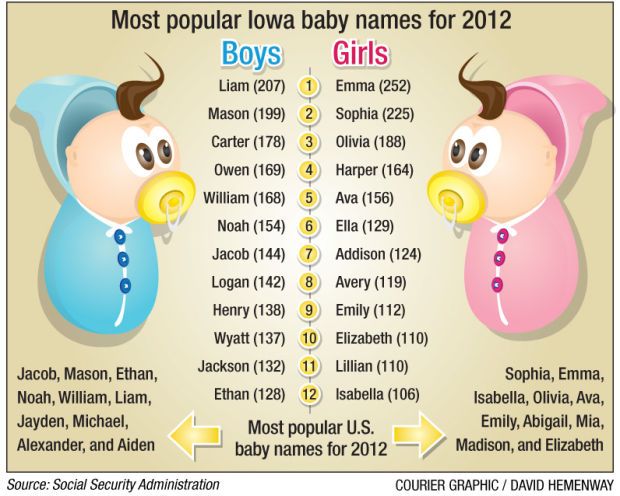

When it’s time to pick out a baby name, it’s beginning to feel like you’ve heard them all. There’s a reason certain names, like Sophie or Emma are considered popular — because there are so many people with those names. Obviously there is nothing wrong with popular names, but some parents to be are looking for names that may be a little less common. Because, as much you may love the name, you don’t really want your kiddo to be one of five Jacksons in his class. We want to give our kids names that may help them stand out a little.

More: 50 Music-Inspired Baby Names by Genre

Often, we turn to baby name websites, or our friend Google. Sometimes those searches can offer great results. But it seems that more often than not, trying to find a name no one’s heard before is practically impossible. Lists are obviously going to push more popular names towards the top of their lists, no matter what.

One of the biggest challenges is finding a name that you’ve really never heard before. Or rather, a name no one else has heard before. Sure, you may go out of your way to find a harder to find name, but then someone finds it to be entirely common. For example, the name Leighton comes up frequently if you do a search for names you’ve never heard of. But many women in their 30s and beyond will likely know the name because of actress Leighton Meester, one of the stars of Gossip Girl.

Making this list was an exercise in what is truly a name you may have never heard of. Upon extensive looking, some names were truly unheard of names, and others were just borderline zany and unique. There were a lot of names that were just alternate spellings of popular (or more well known) names.

- Tallon

- Zariah

- Harlyn

- Alucard

- Farren

- Jaelyn

- Rowan

- Yehuda

- Anwen

- Gage

- Dion

- Torryn

- Enoch

- Britta

- Sveah

- Rhea

- Thaddeus

- Neva

- Bronwy

- Makenna

- Imre

- Greer

- Elora

- Josiah

- Caspian

- Roderick

- Ainsley

- Kyan

- Embry

- Ina

- Augustin

- Bodhi

- Ulani

- Corbin

- Kaia

- Gracen

- Malachi

- Thea

- Delaney

- Yael

- Elora

- Hartley

- Lachla

- Oriana

- Vaughn

- Zuri

- Royce

- Kimya

- Hensle

- Damiah

How many have you heard of?

For more baby name inspiration check out these popular baby name lists:

- Top 1000 Most Popular Baby Girl Names in the U.

S.

- Top 1000 Most Popular Baby Boy Names in the U.S.

- The 100 Coolest Baby Names in the World

Was this article helpful?

Not usefulUseful

Thank you for your feedback.

About the author

Sa’iyda Shabazz

Sa’iyda Shabazz is a writer and mother to one. She can often be found in her apartment writing into the wee hours and trying to read a book in peace. She is a staff writer for Scary Mommy, and writes for several other parenting sites.

View more articles from this author

16 Jewish Baby Names That Were Popular in the 1930s – St Annes Hebrew Congregation

By Glen Berd1 Comment

Boys

1. Joseph. Joseph is a Hebrew boy’s name that means “increase.

2. David. David is a Hebrew boy’s name that means “beloved.” David was the second king of Israel.

3. Harold. Harold is a non-Jewish name that was popular among Jewish people. It is Scandinavian and means “army ruler.” Hal or Harry are fun nicknames.

4. Michael. Michael is a Hebrew name meaning “who is like God.” Michael is also the name of an angel in Jewish tradition.

5. Daniel. Daniel means “God is my judge” in Hebrew.

6. Samuel. Samuel is a Hebrew name meaning “God has heard.” Samuel the prophet anointed the first two kings of Israel.

7.

Girls

8. Barbara. Barbara is a girl’s name that means “stranger.” While it’s not a Hebrew name, it was popular among Jewish immigrants who came to the U.S.

9. Ruth. Ruth is a Hebrew name that means “friendship.” Ruth is the heroine of the Book of Ruth, who cares for Naomi, marries Boaz, and becomes an ancestor of King David.

10. Elizabeth. Elizabeth means “God is my oath” in Hebrew.

11. Martha/Matya. Martha is an Aramaic name that means “the lady.” Matya is a similar sounding name in Hebrew that means “God’s gift.”

12. Judith. Judith is a Hebrew name meaning “praised.

13. Edna. Edna is Hebrew meaning “pleasure.” The Garden of Eden is the setting for the creation story.

14. Sarah/Sara. Sarah is a Hebrew name meaning “princess.” In the Bible, Sarah, the first matriarch, was the wife of Abraham and mother of Isaac.

15. Sharon. Sharon is a Hebrew girl’s name meaning “the coastal plain of Israel.”

16. Alma. Alma is a Hebrew name meaning “young woman.”

NEWS

Search for:

Recent Posts

how did they choose names for children in Rus’?

Author Alexander Bikuzin To read 5 min Views 1.2k. Published

Popular wisdom says: «With a name — Ivan, and without a name — a blockhead.» It’s in the vernacular.

But where did the names come from in Russia and whether they were always a «sweet gift» we will try to find out now.

Contents:

- How were the names chosen for the children of the ancient Slavs?

- Names in Christianity

- What has changed after the revolution?

- Children’s names after the Second World War

- Conclusion

How were the names chosen for children among the ancient Slavs?

Before the adoption of Christianity among the Slavs, the names were chosen by the parents. They had a certain semantic meaning, they were « speaking names «. For example, the third son was called Tretiak, the beloved and long-awaited daughter — Lyubava, and if they wanted the boy to grow up obedient and kind, they called him Dobrynya.

Children were also named Svetlana, Krasava, Zabava, Milusha, Dobromysl, Mstislav, Svyatoslav, Yaropolk, Svyatopolk, etc. Our ancestors were people extremely superstitious , and therefore one should not be surprised that many names resembled nicknames: Wolf Tail, Nelyub, Zhdan, Ghoul, Kruchina, Gloomy, Love, etc.

In the traditions of the Slavic peoples, associated with naming, there have always been rules (more often prohibitions). A newborn should not be given a “name for a name”, i.e. it was not possible to use a name that already has one of the people living in the same house .

Otherwise, one of the people with the same name may die. The signs are based on the belief that each name has its own guardian angel , who is not able to keep track of two people at once in the same house.

In addition, in Rus’ it was often customary to hide the real name (given at baptism), exposing a false name.

Names in Christianity

After the adoption of Christianity, the name for the child began to be chosen according to calendar .

Parents or a priest made a choice from names corresponding to the eighth day after birth, on this day the child was baptized. In the holy calendar there were names of various origins: Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Persian. Many of these names Russified and began to be perceived by the Russian people as their own, Slavic.

So Stefan became Stepan, Theodor became Fedor. The name Ivan (John) is found in the complete calendar 170 times (!) , i.e. almost every other day, that’s why there were so many Ivanovs in Rus’! True, sometimes the priest made concessions and , at the request of the parents, gave a different name , which on this day was not listed in the calendar.

Slavic names Vera, Nadezhda, Lyubov in pre-revolutionary times were often given to children, despite the fact that Vera is found in the calendar only twice a year, and Nadezhda and Lyubov only once.

The most common names in the calendar are: Peter, Pavel, Alexander, Andrey, Mikhail, Maria, Anna and Elena. But Olga, Tatyana, Alla, Lyudmila and Ekaterina have only one birthday.

There were, however, names that carried an unpleasant semantic load , for example, Ardalion — filthy, Claudia — lame-footed, Varvara — rude, Vassa — desert, Foka — seal, and some sounded very dissonant and even comical: Dog, Dul, Proskudnya, Pavsikaky, Agathonus.

But, in any case, the child was given the name that was in the calendar, no «freethinking» was allowed here.

What has changed since the revolution?

Parents found themselves in a different position after the Great October Socialist Revolution. Registration of newborns began to be carried out by civil registry offices (ZAGS), and parents could now choose any name and even could invent a new .

A lot of names were formed from revolutionary slogans , for example, Ikki (Executive Committee of the Communist International), Roblen (born to be a Leninist), Revdit (revolutionary child), the names became popular: Oktyabrina (October Revolution), Vladlen (VLADIMIR LENIN) .

Taking advantage of the freedom of choice, parents gave their children sometimes very strange and unusual names . Geographical names — Altai, Amur, Kazbek, technical names — Hypotenuse, Algebrina, Tractor, Turbine, etc.

At the same time, the influx of foreign names is increasing : Robert, Eduard, Eric, Zhanna, Josephine. By the middle of the 19th century. for every twelve purely Russian names worn, there were at least a thousand «imported» ones — of foreign origin.

Baby names after WWII

«Fashionable» names of the 20-30s did not stand the test of time, and after the Great Patriotic War, children began to be called the usual names , although some of them continued to live in the names of their fathers and grandfathers.

In the 1950s and 1960s, many Lyudmil, Tatyan, Galin, Vladimirov, Valeriev, Viktorov were born. In the 70s, Oksana, Marina, Irina, Elena, Olga appeared, among the boys — Denis, Sergey, Alexandra, Alexei, Andrey. In the 80-90s, Alina, Victoria, Arina, Karina, Nikita, Maxima, Artyoma came into fashion.

Conclusion

The name is directly related to nationality. Receiving the name of his people, the child involuntarily begins to reckon himself with his history and character.

At present, it can be noted that gradually lost traditions come to life . Now many, choosing a name for a newborn, prefer national traditions of naming. Which, of course, speaks of the awakening of interest in the history of their country, of showing respect for their roots and ancestors.

A name is part of a person, part of our history.

Russians in Hollywood in the 1930s

Archival project «Radio Liberty this week 20 years ago». The most interesting and significant of the Radio Liberty broadcast twenty years ago.

Difficulties, successes, failures of Russian silent film stars in the West in the 1930-40s, the fashion for Russian and the influence of Russian style on European and American cinema. First aired 6 Feb 1997.

Ivan Tolstoy : My interlocutor is Natalya Nusinova, a Moscow film historian, who is familiar to our listeners from a number of programs on the history of Russian cinema. The topic of today’s conversation is Russians in Hollywood. On our waves, Natalya Nusinova has already talked about Russian actors and filmmakers in pre-war Europe, mostly in the 1920s. Now the scene will move across the ocean and will be devoted to the next decade, the years of the 1930s. Many of the Russian filmmakers who first emigrated to Europe then moved to America. And when did this process begin and what pulled them across the ocean?

com/player/?url=//soundcloud.com/radio-svoboda/30-3ee»>

Natalya Nusinova : In most cases, America was like a second stage of emigration for filmmakers. You can even say that it was re-emigration from Europe. Like a new search for happiness. For Mozzhukhin, for example, this happened in 1925. He just starred in the film «Casanova» by Alexander Volkov and immediately went to America to try his hand there. True, he starred in only one film, in 1927, directed by Edward Sloman, the film was called «Hostage», was not very successful. Mozzhukhin tried in every possible way to adapt to Hollywood stereotypes, he underwent plastic surgery, his famous long nose was cut off, but he did not become a Hollywood hero. They also shortened his last name, from Mozzhukhin he became Moskin. True, by the way it is spelled (I found his brother’s letters in the archive), I realized that, rather, he called himself Moskvin, because this surname is spelled through «u», but no one there understood it.

Mozzhukhin tried to adapt to Hollywood stereotypes, he underwent plastic surgery, his famous long nose was cut off, but he did not become a Hollywood hero

Maybe even in this name change there was a desire to encode the idea of victory — Victor. Dmitry Bukhovetsky came from Germany. Fedor Otsup, who in general was such a cinematic cosmopolitan, our Soviet Max Ophuls, he made films all over the world, in the late 40s he came to America. But the basis of the American film emigration was Olga Baklanova, Alona Azimova, Vladimir Sokolov, Maria Uspenskaya, Richard Boleslavsky, Akim Tamirov, the famous actor, Mikhail Arshansky and many others. Mikhail Chekhov already belongs to the second wave — he came to America at 1943 year.

Ivan Tolstoy : Was the position of filmmakers in America different from their position in Europe?

Natalya Nusinova : In this regard, it is best to recall the words of Nina Berberova.

Ivan Tolstoy : Well, well, the Hollywood myth is usually a fairy tale about success and fabulous enrichment, but in relation to Russian filmmakers of the first wave, did this myth justify itself in general?

Natalya Nusinova : The fates were, of course, different, and one cannot generalize, but it seems to me that, in general, the story of the Evreinov family’s trip to Hollywood is quite typical. The wife of Nikolai Nikolaevich Evreinov, playwright, director, theorist and theater historian, Anna Alexandrovna Kashina-Evreinova, recalled in her memoirs how, at the very beginning of their life in exile, in a difficult period for them financially, on May 1925 years in Paris, she posed for a portrait of the artist Sorin.

Advertising representing Russian silent film actors in America. 1917

This, of course, is such an extremely sad story of the American experience of the Evreinovs, but it cannot be said that America turned out to be manna from heaven for Russian emigrants in general.

Ivan Tolstoy : Tell me, please, by the beginning of the 1930s, when the main wave of Russian emigrants moved to America, cinema was already sound. How did this affect the position of Russian filmmakers? And, first of all, the actors?

Natalya Nusinova : You are absolutely right when you link these two topics, because the problems of Russians in America, of course, were to a very large extent connected with the arrival of sound in cinema, with the problem of language.

…the problems of Russians in America, of course, were connected to a very large extent with the arrival of sound in cinema, with the problem of language. It was not only an American problem, it was a problem for Russian actors all over the world

In Hollywood it was a problem for all foreign stars, the rare exception was a foreign star who fit into the Hollywood sky. Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Ingrid Bergman — these are perhaps a few names that can be listed in this regard.

Ivan Tolstoy : Have Russian filmmakers in America ever tried to set up their own Russian studio?

Natalya Nusinova : Vladimir Ivanovich Nemirovich-Danchenko had such an idea, who visited Hollywood in 1926 and proposed the creation of a Russian film studio, where, as he wrote, «Russian art, those techniques, the spirit that constitutes the features of the Russian theater, Russian music, Russian literature, which has worldwide success.

Photo by Nemirovich-Danchenko with a dedication to Evgeny Vakhtangov, 1922

Ivan Tolstoy : Please tell me, is the idea of creating a Russian studio in America, was it up in the air or was it based on some American interest in Russia?

Natalya Nusinova : Of course, there was interest, and even very great. Somewhere since the late 1920s, many Russian émigré publications in Europe have noted the fascination of American filmmakers with the realities of Russian life.

Ivan Tolstoy : Has Hollywood’s interest in this «land of ice and polar bears» changed over time? Has it turned into an interest in the Soviet Union?

Natalia Nusinova : I would rather say that the Soviet myth replaced the Russian myth. There was an attempt to mythologize Soviet Russia in the same way as pre-revolutionary Russia was mythologised. It’s just that the «land of ice and polar bears» was replaced by the country of the Kremlin and Lenin’s portraits. There were such films as «Moscow mission» by Curtis or «Song about Russia» by Grigory Ratov with Mikhail Chekhov as the father of the heroine. The most famous film about the Soviet Union was made by non-immigrants. It was «Ninochka» by Lyubich. But the difference is that «Ninochka», which in our USSR for a long time was considered an anti-Soviet evil film, is a deliberate satire, and «Song of Russia» is a spontaneous parody, conceived as a love melodrama. The closest thing in terms of genre to «Song of Russia» and similar films is the operetta.

In «Ninochka» Greta Garbo in a pioneer tie is marching on Red Square on the day of the parade, and this is a parody. And in the «Song of Russia» the heroine-collective farmer performs a concerto for pianoforte by Tchaikovsky at the conservatory, and after that drives around the village on her tractor , are made with sympathy for an ally, and therefore this is an awkward attempt to adopt a formation that looks like a parody. The representation of Soviet life in a film that glorifies the USSR and parodies the Soviet of Deputies is no different from each other. In Ninotchka, Greta Garbo, wearing a pioneer tie, marches through Red Square on the day of the parade, and this is a parody. And in The Song of Russia, the heroine-collective farmer performs Tchaikovsky’s piano concerto at the conservatory, and after that she drives around the village on her tractor, which she herself drives, and this is without ridicule. Most likely, the genre of such films as «Song of Russia» can be defined as pro-Soviet kitsch.

Ivan Tolstoy : What did the idea of creating émigré cinema in America degenerate into, or I will formulate my question this way: what is the fate of Russian filmmakers in the West as a whole?

Natalya Nusinova : Perhaps, summing up our conversation with you both in that part of it that concerned Europe and that part of it that concerned Hollywood, we can say that gradually the idea of creating Russian cinema in the West resulted in what was quite naturally, into the assimilation of Russian filmmakers in Western cinema. In Europe, this process was slower, America subjugated filmmakers almost immediately. But in both cases, the unexpected result was that a Russian myth was created, which the filmmakers brought with them, a myth was created about Russia in cinema, whether it be a myth about pre-revolutionary Russia, or a myth about Soviet Russia. And the Russian style, in addition to the will of the filmmakers themselves, began to influence the development of Western cinema.

S.

S.