Anglo saxon facts 10: Top 10 Facts about The Anglo-Saxons — Fun Kids

Posted onAnglo-Saxons: facts for kids | National Geographic Kids

Prepare for battle kids, because we’re about to take a trip back in time in our Anglo-Saxon facts, to a time 1,600 years ago when fierce warriors ruled Great Britain!

Ever wondered what it might be like stepping foot in Anglo-Saxon England? Find everything you’ll ever need to know about these fierce people in our mighty fact file, below…

Did you know that we have a FREE downloadable Anglo-Saxons primary resource? Great for teachers, homeschoolers and parents alike!

Anglo-Saxon facts: Who were they?

The Anglo-Saxons were a group of farmer-warriors who lived in Britain over a thousand years ago.

Made up of three tribes who came over from Europe, they were called the Angle, Saxon, and Jute tribes. The two largest were the Angle and Saxon, which is how we’ve come to know them as the Anglo-Saxons today.

They were fierce people, who fought many battles during their rule of Britain – often fighting each other! Each tribe was ruled by its own strong warrior who settled their people in different parts of the country.

When did the Anglo-Saxons invade Britain?

The Anglo-Saxons first tried invading in the 4th century, but the Roman army were quick to send them home again! Years later – around 450AD – the Ancient Romans left Britain, the Anglo-Saxons seized their chance and this time they were successful!

They left their homes in Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark and sailed over to Britain on wooden boats. Many of them were farmers before they came to Britain and it’s thought they were on the look-out for new land as floodwaters back home had made it almost impossible to farm.

Anglo-Saxon houses

The Anglo-Saxons didn’t like the stone houses and streets left by the Romans, so they built their own villages. They looked for land which had lots of natural resources like food, water and wood to build and heat their homes, and Britain’s forests had everything they needed.

We know what Anglo-Saxon houses were like from excavations of Anglo-Saxon villages. They were small wooden huts with a straw roof, and inside was just one room in which the whole family lived, ate, slept and socialised together – much like an ancient version of open-plan living!

The biggest house in the village belonged to the chief, which was large enough to house him and all his warriors – and sometimes even the oxen, too! It was a long hall with a stone fire in the middle, and hunting trophies and battle armour hung from its walls. There were tiny windows and a hole in the roof to allow smoke to escape.

Anglo-Saxon place names

Many towns and villages still carry their Anglo-Saxon names today, including “England” which comes from the Saxon word “Angle-Land”.

Early Anglo-Saxon villages were named after the leader of the tribe so everyone knew who was in charge.

The Anglo-Saxons settled in many different parts of the country – the Jutes ended up in Kent, the Angles in East Anglia, and the Saxons in parts of Essex, Wessex, Sussex and Middlesex (according to whether they lived East, West, South or in the middle!)

Not all Roman towns were abandoned, though. Some chiefs realised that a walled city made for a great fortress, so they built their wooden houses inside the walls of Roman towns like London.

Anglo-Saxon food

Perhaps one of our favourite Anglo-Saxon facts is how much they liked to party! They loved a good meal and would often host huge feasts in the chief’s hall. Meat was cooked on the fire and they ate bread, drank beer and sang songs long into the night!

They grew wheat, barley and oats for making bread and porridge, grew fruit and vegetables like carrots, parsnips and apples, and kept pigs, sheep and cattle for meat, wool and milk.

They were a very resourceful people – everything had its use and nothing went to waste. Animal fat could be used as oil for lamps, knife handles could be made out of deer antlers and even glue could be made from cows.

Anglo-Saxon clothes

Anglo-Saxons made their own clothes out of natural materials. The men wore long-sleeved tunics made of wool or linen, often decorated with a pattern. Their trousers were woollen and held up by a leather belt from which they could hang their tools such as knives and pouches. Shoes were usually made out of leather and fastened with laces or toggles.

The women would wear an under-dress of linen or wool and an outer-dress like a pinafore called a “peplos” which was held onto the underlayer by two brooches on the shoulders. Anglo-Saxon women loved a bit of bling and often wore beaded necklaces, bracelets and rings, too!

Anglo-Saxon gods

Grand stone buildings, such as Westminster Abbey, replaced the wooden Anglo-Saxon structures after the Normans invaded in 1066.

Many of today’s Christian traditions came from the Anglo-Saxons, but they weren’t always Christians. When they first came over from Europe they were Pagans, worshipping lots of different gods who they believed looked different parts of their life, such as family, crop growing, weather and even war.

The Anglo-Saxons would pray to the Pagan gods to give them good health, a plentiful harvest or success in battle.

It wasn’t until the Pope in Rome sent over a missionary – a monk called Augustine – to England in 597AD, that the Anglo-Saxons became Christians. Augustine convinced the Anglo-Saxon King Ethelbert of Kent to convert to Christianity and slowly the rest of the country followed suit. Pagan temples were turned into churches and more churches (built of wood) started popping up all over Britain.

Who invaded after the Anglo-Saxons?

From 793AD, the Vikings invaded Anglo-Saxon Britain several times, plundering and raiding towns and villages along the British coastline.

A descendant of Viking raiders, William brought his army of Normans to Britain to take on the new king, and on 14 October 1066, the two armies fought at the Battle of Hastings. The Normans were victorious and Harold was killed. This signalled the end of Anglo-Saxon rule in Britain.

Check out our vicious Viking facts, here!

The Anglo-Saxon period of history shaped many parts of England as we know it today – the words we use for the days of the week for example. Have a go at saying them out loud, below!

Monandæg

Tiwesdæg

Wodnesdæg

Ðunresdæg

Frigedæg

Sæternesdæg

Sunnandæg

What did you think of our Anglo-Saxon facts, gang? Let us know by leaving a comment, below.

Likes

The Anglo-Saxons | TheSchoolRun

Who were the Anglo-Saxons?

The Anglo-Saxons came to England after the Romans left in the year 410. Nobody was really ruling all of England at the time – there were a lot of little kingdoms ruled by Anglo-Saxons that eventually came together as one country.

The earliest English kings were Anglo-Saxons, starting with Egbert in the year 802. Anglo-Saxons ruled for about three centuries, and during this time they formed the basis for the English monarchy and laws.

The two most famous Anglo-Saxon kings are Alfred the Great and Canute the Great.

Top 10 facts

- The Anglo-Saxons are made up of three tribes who came to England from across the North Sea around the middle of the 5th century: the Angles, Saxons and Jutes.

- For a long time, England wasn’t really one country – Anglo-Saxon kings ruled lots of little kingdoms across the land.

- Egbert was the first Anglo-Saxon king to rule England. The last Anglo-Saxon king was Harold II in 1066.

- The two most famous Anglo-Saxon kings are Alfred the Great and Canute the Great.

- The Anglo-Saxon period covers about 600 years, and Anglo-Saxon kings ruled England for about 300 years.

- We know how the Anglo Saxons lived because archaeologists have found old settlements and excavated artefacts like belt buckles, swords, bowls and even children’s toys.

- We can also read about what happened during Anglo-Saxon times in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles.

- Anglo-Saxons once worshipped lots of different gods that they believed controlled all areas of life, but around the 7th century many converted to Christianity after the arrival of the missionary St. Augustine from Rome.

- Some of our modern English words, such as the days of the week, come from the Anglo-Saxon language (sometimes called Old English).

- Anglo-Saxons lived in small villages near rivers, forests and other important resources that gave them everything they needed to care for farm animals, grow crops and make things to sell.

Anglo-Saxon Timeline

-

410

The Romans left Britain, leaving it unguarded by armies and open to invasion by others

-

455

The kingdom of Kent was formed

-

477

The kingdom of Sussex was formed

-

495

The kingdom of Wessex was formed

-

527

The kingdom of Essex was formed

-

547

The kingdom of Northumberland was formed

-

575

The kingdom of East Anglia was formed

-

586

The kingdom of Mercia was formed

-

597

St.

Augustine came to England and introduced people to Christianity

-

757-796

Offa was King of the kingdom of Mercia and declared himself King of all England

-

802

Egbert was the first Anglo-Saxon king of all England

-

871-899

Alfred the Great ruled

-

1016-1035

Canute the Great ruled as the first Viking king

-

1066

The Battle of Hastings took place, resulting in the Normans defeating the Anglo-Saxons

Boost Your Child’s Learning Today!

- Start your child on a tailored learning programme

- Maths & English resources delivered each week to your dashboard

- Keep your child’s learning on track

Trial it for FREE today

Did you know?

- We know how the Anglo-Saxons lived because we’ve found items that they once used buried in the ground – archaeologists excavate spots where Anglo-Saxons houses used to stand – and we’ve been able to figure out a lot about what their lives were like.

- A famous Anglo-Saxon archaeological site is Sutton Hoo, where a whole ship was used as a grave! An Anglo-Saxon king was buried inside the ship along with some of his possessions, such as his helmet and sword.

- We know what the Anglo-Saxons did because of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, a collection of events that people back then wrote every year – kind-of like a yearly summary of important events.

- An instrument that people in Anglo-Saxon times would play is the lyre, which is like a small harp.

- The names of days of the week are similar to the words that the Anglo-Saxons used – for instance, ‘Monandoeg’ is where we get Monday from, and ‘Wodnesdoeg’ is where we get Wednesday from. Some of the names of the days of the week were named after Anglo-Saxon gods. ‘Wodnesdoeg’ is named for the god Woden – it mean’s ‘Woden’s day’.

- Anglo-Saxon uses many of the letters found in Modern English (though j, q, and v are not included and the letters k and z are very rarely used) as well as three extra letters: þ ð æ

- Anglo-Saxons mostly lived in one-room houses made from wood, with thatched roofs.

Important people in the village would live in a larger building with their advisors and soldiers – this was called the hall.

Anglo-Saxon gallery

- A map of Anglo-Saxon Britain

- Anglo-Saxon coins

- A replica of an Anglo-Saxon hall (At West Stow Anglo-Saxon Village)

- The helmet found in the ship burial site at Sutton Hoo

- The plaited belt buckle with a dragon design found at Sutton Hoo (Photo Credit: Jononmac46 via Wikipedia)

- How Anglo-Saxon warriors would have dressed

- Anglo-Saxon runes

- Shoes worn in Anglo-Saxon times

- A statute of Alfred the Great in Winchester

- Canute the Great

Gallery

About

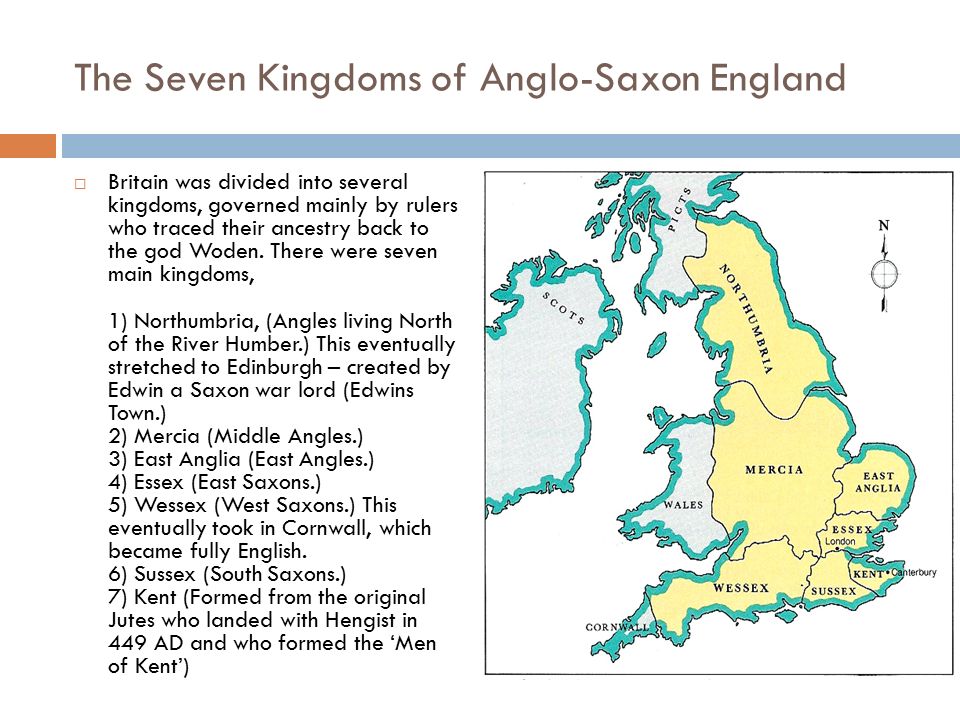

When the Romans left Britain, the country was divided up into a lot of smaller kingdoms and sub-kingdoms that often fought with each other and against any invaders who tried to take over.

By the 800s, there were four main kingdoms in England: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia and Wessex.

One of the most well-known kings from Merica was Offa. He declared himself the first ‘king of the English’ because he won battles involving kings in the surrounding kingdoms, but their dominance didn’t really last after Offa died. Offa is most remembered for Offa’s Dyke along the border between England and Wales – it was a 150-mile barrier that gave the Mericans some protection if they were about to be invaded.

Religion changed quite a bit in Anglo-Saxon times. Many people were pagans and worshipped different gods who oversaw different things people did – for instance, Wade was the god of the sea, and Tiw was the god of war.

In 597, a monk named St. Augustine came to England to tell people about Christianity. The Pope in Rome sent him there, and he built a church in Canterbury. Many people became Christians during this time.

Everyone in Anglo-Saxons villages had to work very hard to grow their food, make their clothes, and care for their animals.

There are nine versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles still around today – this is because copies of the original were given to monks in different monasteries around England to keep up-to-date with information about the area where they lived. Nobody has ever seen the original Anglo-Saxon Chronicles that the copies were made from.

Beowulf is an Anglo-Saxon heroic poem (3182 lines long!) which tells us a lot about life in Anglo-Saxon times (though it is not set in England but in Scandinavia). Beowulf is probably the oldest surviving long poem in Old English. We don’t know the name of the Anglo-Saxon poet who wrote it, but it was written in England some time between the 8th and the early 11th century.

The Anglo-Saxons minted their own coins – they made different designs that were pressed onto the face of a coin, so archaeologists who find those coins today know when they were used.

Vikings from the east were still invading England during the time of the Anglo-Saxons. Sometimes, instead of fighting the Vikings, people would pay them money to leave them in peace. This payment was called Danegeld.

Alfred the Great was based in the kingdom of Wessex, and his palace was in Winchester. He won battles against invasion by the Danes, and he improved England’s defences and armies. Alfred established a strong legal code, and began the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles as a way of recording annual events. He also thought education was very important and had books translated from Latin into Anglo-Saxon so more people could read them and learn.

Canute the Great was the first Viking king of England. A famous story about Canute is that he proved to his courtiers that he wasn’t all-powerful just because he was King. They would flatter him by telling him that he was “so great, he could command the tides of the sea to go back”.

Names to know (Anglo-Saxon kings of England, listed in order)

Egbert (King from 802-839) – Egbert was the first king to rule all of England.

Ethelwulf (King from 839-856)

Ethelbald (King from 856-860)

Ethelbert (King from 860-866)

Ethelred (King from 866-871)

Alfred the Great (King from 871-899) – Alfred the Great is remembered for his victories against Danish invasion, his belief in the importance of education, and his social and judicial reform.

Edward I, the Elder (King from 899-924)

Athelstan (King from 924-939)

Edmund I (King from 939-946)

Edred (King from 946-955)

Edwy (King from 955-959)

Edgar (King from 959-975)

Edward II, the Martyr (King from 975-979)

Ethelred II, the Unready (979-1013, 1014-1016)

Sweyn (King from 1013-1014)

Edmund II, Ironside (King in 1016)

Canute the Great (King from 1016-1035) – Canute was a Viking warrior, and the first Viking king of England. He won a battle against Edmund II that divided their kingdoms, but when Edmund died Canute ruled both kingdoms.

Harold Harefoot (King from 1035-1040)

Hardicanute (King from 1035-1042)

Edward III, The Confessor (King from 1042-1066) – Edward the Confessor had Westminster Abbey built.

Harold II (King in 1066) – Harold II was the last Anglo-Saxon king of England. He died during the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

Edgar Atheling (King in 1066) – Edgar Atheling was declared King after King Harold II died during the Battle of Hastings, but never took the throne. The next king was William the Conqueror, a Norman.

Related Videos

Just for fun…

- Make Anglo-Saxon Collector Cards and play some games with them

- Take an Anglo-Saxons quiz to see what you know about Anglo-Saxon kings, kingdoms and culture in Britain

- Play a Grid Club Anglo-Saxons game

- Write in Anglo-Saxon runes

- Print out some Anglo-Saxon Highlight Cards

- Turn the pages of the Lindisfarne Gospels, a famous Christian manuscript

- Cook like the Anglo-Saxons with this recipe for Anglo-Saxon Oat Cakes

- Colour in Anglo-Saxon people

- Learn to sing songs about Anglo-Saxon history, including Alfred the Great, Athelstan, the story of Beowulf and the end of Anglo-Saxon rule in 1066 at The Battle of Hastings

Books about Anglo-Saxons for children

Find out more about Anglo-Saxons:

- Who were the Anglo-Saxons? Find out in a KS2 guide from BBC Bitesize and watch video clips and animations about the Anglo-Saxon world

- An introduction to the Anglo-Saxon world from the British Library

- Amazing facts about the Anglo-Saxons from National Geographic Kids

- Britons, Saxons, Scots and Picts: loads of information to explore

- Find out about the Anglo-Saxon kings

- Read kids’ historical fiction set in Anglo-Saxon times

- Learn about Anglo-Saxon religion

- Find out about all aspects of Anglo-Saxon life, from manuscripts to weapons, in a kids’ encyclopedia

- About the Anglo-Saxon language, Old English

- Early Anglo-Saxon Britain maps and information

- Learn to read Anglo-Saxon runes

- Anglo-Saxon coinage and the Danegeld and minting coins

- Find out about the Odda Stone

- The two most famous Anglo-Saxon kings were Canute (or Cnut the Great) and Alfred the Great

- See a diagram of a Saxon village

- Find out about food and in Anglo-Saxon times and their grand feasts

- Learn about Beowulf and his battles against the monster Grendel (and Grendel’s mother)

- Download an information booklet about Anglo-Saxon Teeside

- Examine some of the beautiful objects found at Sutton Hoo and see what the excavation site looked like

- An introduction to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

See for yourself

- See the ship burial site at Sutton Hoo

- Visit the reconstructed Anglo-Saxon settlement of Jarrow Hall to find out what life would have been like in Anglo-Saxon times

- Walk along some of the Offa’s Dyke path

- See the largest collection of Anglo-Saxon gold that’s ever been found

- Visit Winchester to see Anglo-Saxon artefacts

- Step into a virtual Prittlewell Burial Chamber and explore the Ango-Saxon objects found in 2003

- See Prittlewell princely burial objects in person, including a gold belt buckle, a flagon and drinking horn and coloured glass vessels and bowls, at Southend Central Museum in Essex

- Look at pictures of sites which tell the story of early Saxon England on the Historic England Blog

- Look at the Anglo-Saxon Mappa Mundi online: created between 1025 and 1050, it contains the earliest known depiction of the British Isles

- Step into a reconstructed Saxon workshop at the Ancient Technology Outdoor Education Centre

- Butser Ancient Farm features archaeological reconstructions of buildings from the Anglo-Saxon period

Also see

10 Fascinating Facts About Anglo-Saxon England that Will Impress Your Friends

10 Fascinating Facts About Anglo-Saxon England that Will Impress Your Friends

The Anglo-Saxons established themselves in England in the 5th century, and gave their name to the country and to an era that stretched from roughly 449 to 1066.

Following are ten of the most interesting things from the history of Anglo-Saxon England.

The Anglo-Saxon Era Saw the Development of the English Language and the Creation of England

The Anglo-Saxons were a Germanic people formed from three different tribes: the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Their settlements gave rise to future kingdoms: the Saxons peopled Essex, Wessex, and Sussex; the Angles East Anglia, Middle Anglia, Nurthumbria, and Mercia; and the Jutes established themselves in Kent. The Angles and Saxons got their names preserved in history. The Jutes, however, were treated like an unwanted stepchild or a third wheel, and their name did not get enshrined in history like that of their partners. Perhaps “Anglo-Saxon-Jutes” was just too much of a mouthful.

In the 300s, the Anglo-Saxons began raiding the Roman province of Britain.

Anglo-Saxon clothing throughout the Medieval era. Wikimedia

The Anglo-Saxon period, from the mid 5th century to the Norman conquest in 1066, saw the creation of England. The Anglo-Saxons arrived as pagans, and reintroduced paganism to what had been a Christian Roman Britain. They began converting to Christianity in the 6th century, after which they experienced a flowering of language and literature, and developed one of Europe’s most vibrant and advanced cultures.

Starting in the late 8th century, it was the turn of the now-Christian, settled, and civilized Anglo-Saxons, to experience at the hands of the Vikings what their ancestors had subjected the Britons to. History seemed to be repeating itself, as the Vikings suddenly erupted with terrifying raids that devastated England, followed by a campaign of conquest and displacement.

By the 870s, the Anglo-Saxons seemed to be on the verge of following the Britons into near oblivion. They were saved by a strong leader, Alfred the Great, who rallied a resistance that halted the Vikings, then pushed them back in a reconquesta that eventually united the Anglo-Saxons lands under a single king. It was in that crucible of resistance to the Vikings that England was forged. The Anglo-Saxons would lose their independence following the Norman conquest in 1066. However, by then the outline of England as a country had already been formed, and would continue on as a going concern, under new management.

The end of Roman rule in Britain, 383 to 410 AD. Wikimedia

The Anglo-Saxons Wrested England From the Romano-British

After the Roman conquest of Britain in the 1st century AD, they formed a province comprised of England, Wales, and parts of eastern Scotland, which experienced centuries of peace, stability, and prosperity. Roman troops from across the Empire were garrisoned in the towns, and many married local Britons.

There were also thousands of Roman officials, businessmen, artisans, and other professionals, who descended upon the province, often bringing their families with them. Together with the Roman military, they formed a sizeable Roman core that transformed Britain and Romanized the native Britons. Hitherto Celtic in language and customs, the indigenous population melded with their conquerors to form a Romano-British culture.

While the bulk of Roman Britain’s population was rural, there was a sizeable urban population numbering in the hundreds of thousands, and the province’s capital, Londinium, had a population of about 60,000. Londinium was a cosmopolitan and ethnically diverse city, inhabited by Britons, as well as people from North Africa, the Middle East, the Rhineland, and the rest of the Roman and Mediterranean world.

Christianity arrived in the 3rd century.

Roman citizenship was granted to a steadily growing number of native Britons, and in 212, Roman citizenship was granted to all free men throughout the Roman Empire, and all free Britons became Romans. By the 4th century, Britain had been transformed into one of the most loyal provinces of the Roman Empire. Then the bottom fell out, when the Romans abruptly left the island, and told the natives to take care of and look out for themselves.

Saxon warriors. Realm of History

The Saxons Were Brought to England as Mercenaries

As the Roman Empire came under mounting pressure from barbarians, the authorities had a correspondingly greater need for all the soldiers they could get to protect the Roman heartland.

In 383, the Western Roman Emperor, Magnus Maximus, began withdrawing Roman troops from western and northern Britain, and left local warlords in charge. This occurred at a time when the province was experiencing raids from Picts to the north, Scoti from Ireland, and Saxons from the continental mainland. The troop drawdown, which continued at a steady pace over subsequent years, led to a massive increase in the frequency and intensity of those raids.

By 410, the Romano-British had grown exasperated with the Roman authorities’ failure to protect Britain from attacks by increasingly bold barbarians. So that year, they expelled the officials of a Roman usurper, then wrote the emperor Honorius, seeking aid. Honorius, however, was hard pressed at the time by the Visigoths – who would soon sack Rome. His reply to the Romano-British, known as the Rescript of Honorius, told them he had no troops to spare, and advised them to see to their own defense.

Unfortunately for the locals, they proved incapable of uniting to govern themselves or organize a common defense. Of the barbarian raiders, the ones wreaking the most havoc and causing the most alarm were the Picts and Scoti, from Scotland and Ireland, respectively. So somebody had the idea of using one group of barbarians to fight off other barbarians, and a bargain was accordingly struck with some Saxon chieftains from the continental mainland.

It was an arrangement common in the Late Roman Empire and known as foederati, whereby barbarians were settled in imperial territory in exchange for military service. The Saxons were thus brought to Britain and settled in the eastern parts, in exchange for fighting off the Picts and Scoti. It did not work out well for the Romano-Britons, however. The Saxons, once they got themselves settled, liked their new land, and viewing their Briton hosts and patrons as soft weaklings who needed other men to fight for them, decided to help themselves to everything.

Anglo-Saxon migration. Wikimedia

Saxon Mercenaries Seized England From the Native Britons

The Saxons had been raiding the Roman province of Britain throughout much of the 4th century. Then, in one of history’s worst “it takes a thief to catch a thief” brainstorms, the locals struck a deal to settle the Saxons on British soil, in exchange for Saxon promises to defend the rest of the province from other barbarians. It did not take the Saxons long to turn on the locals.

Much of what we know about the Saxons’ displacement of the Romano-Britons comes from De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (“On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain”), penned circa 510 – 530 by a British cleric, Saint Gildas. Another valuable source on the subject is the Venerable Bedes’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written about 731.

According to Gildas, the Saxons began by complaining that the Romano-Britons had skimped on the monthly supplies they had been promised.

The Saxon declared that the locals had rendered the treaty void by failing to live up to its terms, and launched a massive onslaught that engulfed Roman Britain “from sea to sea”. Eventually, Hengist and Horsa forced Vortigern, whom they had reduced to a puppet, to enter into a treaty that ceded large swaths of southeastern England to the Saxons.

The Saxons were not content with those gains, however, and continued attacking the Britons. They launched a war of conquest that sought to seize the entire province, displace the local inhabitants, and replace them with Germanic settlers. The Saxons were joined by the Angles, from today’s Schleswig-Holstein, between Germany and Denmark, and Jutes, from today’s Jutland in Denmark, and Lower Saxony in Germany.

The onslaught lasted for 20 or 30 years, until the hard-pressed Britons won a crucial victory at the Battle of Mons Badonicus, sometime around 500. For some time at least, that stopped the invaders, who by then had overrun about half of what had been the Roman province. It was this period of warfare that gave rise to the stories of King Arthur, the heroic leader of legend who led the Britons against the Saxons.

While King Arthur is a figure of myth, archaeology does support a Saxon setback around 500. The pattern of Saxon settlement steadily expanding westward and replacing the Britons, suddenly reversed, and Briton settlements began expanding eastwards, displacing the Saxons and reclaiming previously lost lands. Thus, accounts of a major Briton victory sometime around 500 are probably true.

That stabilized the border between the Britons and Saxons, and their allied Angles and Jutes. For decades afterwards, the Britons held on to a region west of a crescent running roughly from Dorset on the English Channel to the Derwent River in Yorkshire, with salients jutting north and west of London, and south of St.

The Britons’ reprieve proved only temporary, however. The Anglo-Saxons recovered, and resumed their expansion at the expense of the Britons, eventually conquering and settling nearly all of what is now England. The indigenous Britons lost their most productive lands, and their last independent remnants were pushed into the peripheral regions of Cornwall and Wales.

Stained glass window in Worcester Cathedral depicting Penda of Mercia’s death in battle. Wikimedia

The Anglo-Saxons Divided Their Conquest Into Seven Kingdoms

The Anglo-Saxons created England and gave her their language, but England did not come into being as a country until several hundred years after the Anglo-Saxons’ arrival. In the meantime, they divided their conquered territory amongst themselves into small statelets, which eventually coalesced into seven major kingdoms that came to be known collectively as the “Heptarchy”.

The peoples of those kingdoms – Kent, Sussex, Essex, Wessex, Mercia, East Anglia, and Northumbria – shared a common language, culture, socio-economic conditions, and a pagan religion. However, the similarities did not keep those kingdoms from being fiercely independent, jealously guarding their own prerogatives, and seeking gains at their neighbors’ expense.

At first, the Anglo-Saxons were focused upon their common enemy, the indigenous Britons, and exerted their energies towards further conquests and expansion at the natives’ expense. Once the initial wave of conquests slowed down, and the borders with the Britons had stabilized, the kingdoms of the Heptarchy began vying amongst themselves for dominance.

Warring against each other became something of a national pastime amongst the Anglo-Saxons, until a king Penda of Mercia (reigned 626 – 655) emerged as the fiercest and of the competing warrior kings. One of the last pagan Anglo-Saxon kings, Penda defeated and personally killed some of his rival kings, and sacrificed the Christian king Oswald of Northumbria to the pagan god Woden.

Penda gave rise to a period known as “The Mercian Supremacy”, during which Mercia dominated the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, without uniting the various kingdoms into a single entity, however. That unification would not arrive until more than a century later, when the catastrophe of the Viking descent upon the Anglo-Saxons, and the resistance it engendered, forged what would become “England”.

Augustine before Ethelbert and Bertha. Educational Technology Clearing House, University of South Florida

Saint Augustine of Canterbury Converted the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity

The Roman province of Britain had been largely Christian before it was overrun by the pagan Anglo-Saxons, whose conquered lands reverted to paganism. It was one of the few examples in history of a monotheistic faith getting rolled back from a territory in which it had gained a foothold, to be replaced by paganism. For more than a century after the Anglo-Saxon descent, the only predominately Christian areas in Britain were the lands still controlled by the indigenous Britons.

The re-Christianization of what had once been Roman Britain commenced in 565, when an Irish monk named Columba founded a monastery in the island of Iona, off the western coast of Scotland. That monastery began exerting a spiritual influence over the surrounding pagans, and Christianity gradually spread down the western coast of Scotland, and into northern Britain.

In 595, Pope Gregory the Great selected a Benedictine monk named Augustine, the prior of a monastery in Rome, to lead a mission of Christianization into the lands of the Anglo-Saxons. Augustine was sent to the kingdom of Kent, which dominated southwestern Britain and was ruled by a king Ethelbert, whose wife Bertha was a Christian. It was expected that she would aid the efforts to convert her husband and his people.

Bertha was the daughter of a Frankish king of Paris, and as one of the conditions of her marriage, had brought a bishop to Kent with her.

King Ethelbert allowed Augustine to preach in his capital of Canterbury, and within the year, Augustine had succeeded in converting the king. That led to the establishment of churches throughout Kent, and large scale conversions to Christianity. From Kent, Christianity spread to the neighboring Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in southern Britain. Augustine, considered an “Apostle to the English”, was later canonized as Saint Augustine of Canterbury, and is deemed to be the founder of the Catholic Church in England.

Farther to the north, a king Oswald of Northumbria asked the monastery of Iona in 635 to send a mission to Christianize his kingdom. Oswald had once been forced to flee Northumbria, and found refuge in the Christian enclaves of southwest Scotland.

Oswald would eventually fall to king Penda of Mercia, when the latter rose to dominate the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. After defeating and capturing the proselytizer king, Penda sacrificed Oswald to the pagan god, Woden. However, Christianity had already taken hold in Northumbria by then, thanks to Oswald, who ended up getting canonized as a saint.

Viking raiders. Learning History

The Vikings Nearly Brought the Anglo-Saxon Era to a Premature End

Anglo-Saxon England breathed a collective sigh of relief upon Penda’s death in 655. The era of widespread warfare ushered in by the Mercian king, was followed by one of relative peace, that came to be seen as an Anglo-Saxon golden age. It was a period of economic expansion, which produced a surplus that helped fund a growing number of monasteries – centers of learning in the early Medieval period.

In 669, the Archbishop of Canterbury founded a school in his city – the first school in England. The Venerable Bede would describe it about 60 years later as having “attracted a crowd of students into whose minds they daily poured the streams of wholesome knowledge“. Some of them, who survived into Bede’s own day, were as fluent in Greek and Latin as they were in their native English.

That and other learning institutions produced scholars and poets who wrote in Latin, and one of them, Aldhelm, pioneered a grandiloquent style that became the dominant Latin style for centuries to come. Anglo-Saxon scholars were the most highly respected throughout Europe during this period, and Bede himself was one of the foremost scholars and men of letters in Christendom.

The peoples of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had initially spoke distinctive dialects. However, those different strains melded into each other over time, and evolved to form a common language, known as Old English, which lent itself to an exceptionally rich vernacular literature.

Unfortunately for the Anglo-Saxons, the very prosperity and plenty that fueled their golden age would result in its sudden ending. Anglo-Saxon England’s wealth, and especially the wealth of its monasteries, would attract the covetous attention of Viking raiders. Erupting from Scandinavia in the late 8th century to terrorize Europe and the Mediterranean world, those seaborne raiders nearly brought the Anglo-Saxon era to a premature end.

What came to be known as the Viking Age began in 793, when raiders struck the great monastery at Lindisfarne, massacring the monks and seizing the riches. After generations of peace, the destruction of Lindisfarne was a shock probably equivalent to Pearl Harbor and 9/11 rolled into one. And unlike the US, the Anglo-Saxons lacked the means to strike back, and were unable to even defend their shores from further raids.

Anglo-Saxon England was wholly unprepared for the Viking onslaught, which, ironicallyy, was quite similar to the Anglo-Saxon onslaught upon Roman Britain centuries earlier. In the decades after destroying Lindisfarne, the Vikings continued raiding England, in assaults marked by a wanton savagery, and gratuitous destructiveness that terrorized all and sundry.

For decades, the raiders had always retreated after striking, wintering in their homeland before returning the following spring. By 850, however, they had had grown sufficiently disdainful of Anglo-Saxon resistance to overwinter in England for the first time, in the island of Thanet off Kent. They would repeat that in subsequent years until, in 865, they switched from raiding to outright conquest.

That year, Vikings gathered into what came to be known as “The Great Heathen Army”, landed in East Anglia, then marched northward into Northumbria. There, they established the Viking community of Jorvik – the first Viking settlement in England.

Viking raiders vs Anglo-Saxons. AliExpress

Alfred the Great and His Son Defeated the Vikings and Unified England

For centuries after settling in Britain, the Anglo-Saxons had divided their lands into disparate kingdoms, often competing and warring against each other. It took the invading Vikings, who extinguished some of those kingdoms outright and brought the rest to the brink of extinction, to unify the Anglo-Saxons into the single country of England.

That unification was conducted by Alfred the Great (849 – 899) and his successors. Alfred was the youngest son of king Aethelwulf of Wessex, who set up a succession whereby the throne would get inherited by each of his sons, from oldest to youngest.

Accordingly, Aethelwulf was succeeded in turn by Alfred’s elder brothers Aethelbard, then Aethelbert, then Aethelred. In 868, king Aethelred of Wessex and his younger brother Alfred tried, and failed, to keep the Vikings’ “Great Heathen Army” from overrunning the neighboring kingdom of Mercia. By 870, Wessex was the last independent Anglo-Saxon kingdom, when it was attacked by the largest Viking army assembled to date.

King Aethelred and his brother, Alfred led the defending forces in a series of battles with varying outcomes. Victory in an opening skirmish was followed by a severe defeat a few days later, which in turn was followed by a brilliant victory in the Battle of Ashdown, January 8th, 871, in which Alfred played a leading role.

The new king’s reign commenced inauspiciously, with two defeats. The second defeat in particular, at Milton in May of 871, was a bad one, and it smashed all hopes of driving the Vikings from Wessex by force of arms. Alfred was thus forced to make peace with the invaders, paying them a hefty sum to withdraw from his kingdom – which they did, by the autumn of 871.

The Vikings returned in 876, and Alfred was forced to make a new peace with them, whose terms the invaders soon violated. In 878, the Vikings launched a sudden attack which overran Wessex, and forced Alfred to flee to the marshes of Somerset. He led a guerrilla resistance, before emerging in May of 878 to rally the surviving Wessex forces and lead them to a decisive victory at the Battle of Edington. Alfred then pursued and besieged the Vikings at Chippenham, starved them into surrender, and forced their leader, Guthrum, to convert to Christianity.

In 885, Vikings from East Anglia attacked Kent, but Alfred beat them back, then went on a counteroffensive that captured London. That victory led all Anglo-Saxons not then under Viking rule to accept Alfred as their king – a major step towards the unification of England. London acted as a springboard and base of operations for Alfred’s successor, his son Edward the Elder (reigned 899 – 924). By the end of his reign, Edward had decisively defeated the Vikings, and extended his authority over nearly all of today’s England.

Edmund Ironside. Wikimedia

Edmund Ironside Led a Fierce Resistance Against Danish Invaders

One of the last heroic kings of the Anglo-Saxon era was Edmund II, AKA Edmund Ironside (circa 993 – 1016), England’s king from April 23 to November 30, 1016. He was the son of one of England’s worst kings: the weak and vacillating Ethelred the Unready. The son was a vast improvement over his father, and Edmund proved himself made of sterner stuff than his predecessor.

Starting in 991, Edmund’s father, Ethelred the Unready had unwisely sought to buy off the Danes, who were then occupying northern England. To get them to stop their nonstop raids into his kingdom, Ethelred decided to pay them a tribute known as the Danegeld, or “Danish gold”. Unsurprisingly, all that did was embolden the Danes. Seeing that they were dealing with a pushover, they starting upping their demands, insisting on ever greater tribute payments.

Worse for Anglo-Saxon England, Ethelred had set himself up for extortion without getting anything out of his people’s gold. They Danes collected the tribute, and continued raiding and plundering England, secure in the knowledge that they had little to fear from its weak king. Finally, after over a decade of bankrupting his kingdom and beggaring its people with the high taxes needed to pay the Danegeld, Ethelred snapped.

Understandably, that massacre upset the Danish settlers’ kin and countrymen. The result was an invasion by the Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard, who conquered England in 1013 and forced Ethelred to flee to Normandy. However, Sweyn died the following year, at which point Ethelred returned, and with his son Edmund playing a leading role, chased Sweyn’s son, Canute, out of England in 1014.

Canute returned the following year at the head of a large Danish army, and proceeded to pillage and devastate much of England. However, crown prince Edmund mounted a fierce Anglo-Saxon resistance, which stymied the Danish invaders. When Ethelred died in 1016, Edmund, who by now had earned the nickname “Ironside” because of his toughness and tenacity, succeeded him on the English throne as Edmund II.

Unfortunately for Anglo-Saxon England, their heroic king’s reign proved short lived, as Edmund died not long thereafter, in weird circumstances that demonstrated that even if the king’s sides were iron, his bottom was not.

Norman mounted knights attacking the Saxon shield wall at the Battle of Hastings. Ancient Origins

The Anglo-Saxon Era Ended in 1066, at the Battle of Hastings

Edmund Ironside’s assassination left the path open for the Danish king Canute to become king of England and inaugurate a short lived Scandinavian dynasty. Canute ruled until his death in 1035. He was then followed on the throne of England by his sons Harold Harefoot (reigned 1035 – 1040), and Hartachanut (reigned 1040 – 1042).

Harthacanut’s death in 1042 triggered a succession crisis, and a struggle for the English throne between King Magnus the Good of Norway, and Edward the Confessor, Edmund Ironside’s half brother.

Edward had grown up an exile in the court of the Dukes of Normandy, and was half Norman himself, his mother being the daughter of a Duke of Normandy. He thus had strong Norman ties and attachments, which would cause serious problems down the road and bring the Anglo-Saxon era to an end. Trouble began in 1051, when Edward’s reliance on Norman advisors led to a falling out with Godwin, Earl of Wessex. Godwin was banished and stripped of his lands, but he returned with an army and forced Edward to restore him to power.

After Godwin’s death in 1053, he was succeeded by his son Harold Godwinson as England’s most powerful figure. When Edward the Confessor died childless in 1066, Harold was crowned as king of England. The new king’s title was disputed, however, by his younger brother, Tostig, and by Duke William of Normandy.

King Harold gathered his forces in readiness for a seaborne invasion from Normandy by Duke William, but contrary winds kept the Normans on the other side of the English Channel. It would be Harold’s brother, Tostig, who would strike first. Allied with the Norwegian king Harald Hardrada, Tostig landed with a largely Scandinavian army near York, in the north of England.

Harold, who had had been encamped in the south of England, waiting for an invasion from Normandy, led a forced march north to York, and surprised his brother and the Norwegian king by his unexpected arrival. In a hard fought battle at Stamford Bridge on September 25th, 1066, Harold won a decisive victory that claimed the lives of most of the invaders, including those of Tostig and Harald Hardrada. Of the 300 ships that had landed the invading army, only 24 were needed to carry the survivors back to Norway.

King Harold did not get to savor the victory for long, however: two days later, the Channel winds finally changed, allowing Duke William to finally land his army in southern England. So Harold assembled his weary troops, and retracing his steps, led them on another forced march back to the south of England, gathering reinforcements along the way as he rushed to meet the new invasion.

Harold approached Duke Williams at Hastings with about 7000 men – a force representing only half of England’s trained soldiers. Harold was advised to wait for reinforcements, but chose instead to offer battle immediately, in order to stop Williams from devastating the countryside. Thus, the Anglo-Saxons met the Norman invaders at the Battle of Hastings on October 14th, 1066.

The Anglo-Saxons assembled atop a protected ridge, where they formed a shield wall, with king Harold occupying the center of the line. However, their tactics and military doctrine, derived from their own Germanic tribal history and reinforced by generations of warfare against the Vikings who fought in similar fashion, were outdated.

The battle commenced with mounted charges by Norman knights, which were beaten back by the Anglo-Saxon shield wall. However, a pair of feigned retreats drew sizeable numbers of Harold’s men from their battle lines into disastrous pursuits, that ended with the pursuers getting surrounded and destroyed. That thinned the Anglo-Saxon lines, and by late afternoon, Harold was hard pressed, when a random arrow struck him in the eye, killing him.

The leaderless Anglo-Saxons fought until dusk, then broke and scattered. The victorious William secured the countryside, then advanced upon and seized London. Now known as William the Conqueror, he was crowned as King William I on December 25th, 1066, bringing the Anglo-Saxon era to an end. The new king established the Norman Dynasty, and inaugurated a new era that reoriented England from the Scandinavian world to that of Continental Europe.

____________

Where Did We Find This Stuff? Sources & Further Reading

BBC History – Alfred the Great

Britain Express – Edward the Elder

Encyclopedia Britannica – Alfred, King of Wessex

Encyclopedia Britannica – Saint Augustine of Canterbury

English Heritage – What Happened at the Battle of Hastings

History Extra – 10 Things You (Probably) Didn’t Know About the Anglo-Saxons

History Today Magazine, Vol. 49, Issue 10, November 1999 – Alfred the Great: the Most Perfect Man in History?

Realm of History – 10 Things You Should Know About the Anglo-Saxon Warriors

St. Columba Heritage Trail – Who Was Saint Columba?

Wikipedia – Anglo-Saxons

Wikipedia Anglo-Saxon Settlement of Britain

Wikipedia – Augustine of Canterbury

10 Important Facts You Should Know About The Anglo-Saxons

28th September 2016

2nd June 2021

By Victor Rouă

In History

BritainMiddle AgesNorsemenVikings

Below you can read a list of 10 important historical facts on the Anglo-Saxons, one of the most significant Germanic peoples of the Middle Ages.

10. The origins of the Anglo-Saxons and the Anglo-Saxon period

The Anglo-Saxons were a confederation of Germanic peoples who initially lived in contemporary northern Germany, southern Denmark, and the northern Netherlands, and sailed across the North Sea to Britain during the Dark Ages.

In British historiography, the Anglo-Saxon period is commonly referred to as the timeline between the mid 5th century (when they built the first settlements in the Albion) to the mid-late 11th century. The end of this historical period coincides as such with the Norman conquest of England which took place in 1066 at the Battle of Hastings.

According to ‘Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum’ (‘The Ecclesiastical History of the English people’) written by Saint Bede the Venerable, an important early medieval historian, the Anglo-Saxons were largely descended from the Angles (who came from Schleswig), the Saxons (who also lived in ancient times in Schleswig and around the Baltic coast), and the Jutes (from Jutland, modern day Denmark).

9. The language of the Anglo-Saxons

It is still debatable among historians whether or not the Angles and Saxons spoke the same language when they came to Britain during the mid 5th century. However, the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ commonly refers to the language spoken by them in England as well as eastern Scotland, from the 5th century to the 12th century. Scholarly, Old English is the preferred denomination for the language though. The Old English language was written in insular (Gaelic) script or in Anglo-Saxon (Futhorc) runes from the 5th century to the 12th century.

Excerpt from the Lindisfarne Gospels, a fine work of Insular (Hiberno-Saxon) Art. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

8. The correct usage of the term Anglo-Saxon

When referring in a historical context the term Anglo-Saxon, one must bear in mind the fact that ethnically it may denote equally Angles and Saxons, but the Anglo-Saxons didn’t call themselves as such.

Furthermore, it was only during the 8th century that the term Anglo-Saxon was firstly attested, but only to make a clear discrepancy between the Saxons who settled in Britain and those from continental Europe. Thus, in the works of Saint Bede the Venerable, the latter were called ‘Antiqui Saxones’ (i.e. ‘Old Saxons’). This denomination was actually part of an important hierarchic title, namely ‘rex Angul-Saxonum’ (i.e. ‘King of the Anglo-Saxons’).

7. Early Anglo-Saxon Age

The early Anglo-Saxon Age in Britain started right after the end of the Roman rule. In the wake of the ever prolonged decadence of the Roman Empire at the round of the 5th century, Britain was relatively long regarded as a peripheral province. It is generally agreed that by the mid 500’s the Romans lost any sort of authority in Britannia.

So it is that during the Migration Era — which took place during the early Middle Ages in Europe and was mainly triggered by the expansion of migratory peoples, among which were also various Germanic tribes — the Romano-Britons initially harshly opposed the territorial expansion of the Germanic invaders, being led by prominent legendary figures as Arthur or Vortigern (whose real identities are hardly documented), but were ultimately defeated and subdued by the beginning of the 7th century.

6. Anglo-Saxon kingdoms

After successfully settling Britain, the Anglo-Saxons founded four important kingdoms which will eventually form the basis for the Kingdom of England. These were East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria, and Wessex. There were also three additional noteworthy ones known as Essex, Kent, and Sussex. The latter were conquered by the neighbouring kingdoms at some point in history.

Detailed map depicting the seven Saxon kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England by John Speed in ‘Theatre of the Empire of Great Britanie’ (17th century). Image source: Wikimedia Commons

In addition, other Anglo-Saxon polities also existed, but were to a smaller extent worthy to play an important part in early medieval Britain. Some of them were Isle of Wight, Lindsey or Surrey. Most importantly, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex were identified as forming the heptarchy (a term to have first appeared in the work ‘Historia Anglorum’ by Henry of Huntingdon during the 12th century).

5. Anglo-Saxon helmets

Only four Anglo-Saxon helmets have been unearthed to date. Among these artefacts, the most notable ones are the Coopergate helmet (which was discovered in York), and the one excavated at Sutton Hoo, an archaeological site situated near Woodbridge, East Anglia. The first dates from the 8th century, while the second possibly belonged to a 7th century Anglo-Saxon nobleman.

Sutton Hoo helmet replica on display at the British Museum in London, UK. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

4. The Norse invasions of Anglo-Saxon England

Due a to a number of debated reasons, the Norsemen started to raid the eastern and southern coastlines of Britain as early as 789, when a group of Norwegian Vikings from Hordaland landed on the Isle of Portland, in the English Channel.

However, the date often given as the start of the Viking Age in England is 793, when another convoy of Norwegian Vikings plundered the Catholic abbey of Lindisfarne, located less than one mile off the north-eastern coast of the Kingdom of Northumbria, now northern England.

During the Viking Age, both Danish and Norwegian Vikings attacked much of the British archipelago, and eventually established kingdoms as well. The Danes established the Danelaw, while the Norwegians controlled the Kingdom of the Isles.

3. The Anglo-Saxons were related to the Vikings

Both the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes were genetically related to the Norsemen, having as such a common Germanic ethnic origin. Since their homelands were northern modern day Germany and the Netherlands, as well as southern modern day Denmark, it goes without saying that their languages also retained a mutual degree of intelligibility over the years that passed their exodus towards Britain.

As in the case of the Vikings, one of the important causes which explains the migration of the Anglo-Saxons to the west is the fact that they needed good farming soils. In Britain, they initially engaged in agriculture after pushing the Celtic-speaking populations northward and westward.

Map depicting the homelands of the Anglo-Saxons coloured in blue (for Jutes), orange (for Angles), red (for Saxons), and yellow (for Frisians).

2. Anglo-Saxon architecture

Generally, the houses built by the Anglo-Saxons were quite simplistic in design. They were constructed using timber with thatch for roofing. When they initially landed in Britain, they preferred to live in small rural communities. Nonetheless, some of them opted to build wooden houses within the walls of the former towns erected by the Romans.

Buildings with thatched-roofs from West Stow Anglo-Saxon village in West Suffolk, England. Image source: Wikimedia Commons by Midnightblueowl

1. Anglo-Saxon coins

It is also quite interesting to note the fact that between 991 and 1018, the Anglo-Saxon kings of England paid an important economic tribute to the Viking invaders worth circa 2.8 million troy oz in silver coins. This explains why today there are still more Anglo-Saxon silver coins in Denmark than in England.

Additional small note: Artistic licence was used for the horns designed on the helmets worn by these Vikings.

Documentation sources and external links:

- End of Roman rule in Britain on www.wikipedia.org (in English)

- Anglo-Saxons on www.wikipedia.org (in English)

- Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain on www.wikipedia.org (in English)

- Heptarchy on www.wikipedia.org (in English)

- Lindisfarne Gospels on www.wikipedia.org (in English)

- Anglo-Saxon architecture on www.wikipedia.org (in English)

- Vortigern on www.kingarthursknights.com

- The Anglo-Saxons on www.bbc.co.uk

- Anglo-Saxons: a brief history on www.history.org.uk

- Anglo-Saxon on www.britannica.com

- Saint Bede the Venerable on www.britannica.com

- Ecclesiastical History of the English people on www.britannica.com

- Angle on www.britannica.com

- Saxon on www.britannica.com

- England c.450-1066 in a Nutshell on www.anglo-saxons.

net

- The Sutton Hoo Helmet on www.britishmuseum.org

- The York Helmet on www.historyofyork.org.uk

- 10 things you (probably) didn’t know about the Anglo-Saxons on www.historyextra.com

- 10 Little-Known Facts About The Anglo-Saxons on www.listverse.com

Liked it? Take a second to support Victor Rouă on Patreon!

Top Ten Fascinating Facts about the Anglo-Saxons

Settlement in England

The Anglo-Saxons were Germanic invaders who came from what is now the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. They were from the tribes known today as the Angles, Saxons, Frisians and Jutes and set up their own kingdoms in England. The Angles established themselves in the north and east, founding the kingdoms of Northumbria and East Anglia, the Jutes settled in Kent in the far southeast of England, the Saxons took the south of the country, naming their nations Wessex and Sussex. The Frisians made a home throughout the kingdoms of the other tribes, often working as traders.

Language

The Anglo-Saxons spoke various Germanic dialects which eventually evolved into the language Old English, which is the direct ancestor of modern English. A quarter of all English words come from Old English, although these words are very commonly used for everyday objects for example day, night, light, yes, he, she, god, cold and rain. Even today the closest language to modern English is still Frisian, the language spoken in the north of the Netherlands by the descendants of the people who became the Anglo-Saxons in Britain.

Weekdays

The Anglo-Saxons gave us the names for our days of the week. Names like Monday meaning “Moon-Day”. Tuesday was Tiw, the one-armed war-God’s Day and Wednesday, the day in honour of their chief God Woden, who was known as Odin to the Vikings. However the Viking God Thor was called Thunor in Old English, so Thursday is the only Viking based day of the week in the English language today. They also had names for the remaining days of the week, Friday was “Frigeday” for Frigg, the Anglo-Saxon name for Venus, Saturday was “Saternusdag” and Sunday was “Sunnandag”

Bad Neighbors

Archaeologists still don’t know what happened to the people the Anglo-Saxons replaced.

However scholars don’t know what happened to the millions of people living in the land the Anglo-Saxons took over in what is now England and southern Scotland. Gildas suggested that the Britons were slaughtered in their hundreds of thousands by the invaders. New DNA evidence shows that males from Central England are genetically very distinct from those living a few miles west in Wales, whereas compared with the modern Frisians, they are almost inseparable suggesting a complete wipe-out of the pre-Anglo-Saxon population.

Metal Workers

As well as being bloodthirsty warriors, the Anglo-Saxons were skilled craftsmen and metal workers. Using gold and jewels from as far away as Persia, the Anglo-Saxons created beautiful artifacts such as this, the helmet found at Sutton Hoo in Surrey and the items found in the Staffordshire Hoard which was valued at £3.285 million after it was discovered in 2009.

King Arthur

Knights, round tables and damsels in distress may in fact be thanks to the Anglo-Saxons. The legend of King Arthur can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxon invasion when the Celtic Britons were being driven out of their ancient lands by the new invaders. The early form of the legend tells of a vision concerning a white and red dragon each representing the Saxons and the Britons. This red dragon is still on the Welsh flag today. Others tell us that Arthur was a British prince who stopped the Saxons at the siege of Mount Badon, near modern-day Bath. Whatever the truth behind it all, the stories of King Arthur and his knights are now timeless classics throughout the world.

Missionaries

When the Anglo-Saxons came to Britain they worshipped the old Germanic Gods like Woden, Thunor and Frigg, celebrating the harvests and the spring and summer solstices while conducting human and animal sacrifices. However this would change with the exiled Northumbrian King Oswald who sought refuge on Iona where he became a Christian. When he retook his kingdom from the Britons, the people there were forced to accept their ruler’s new religion, converting to Celtic Christianity which was brought to them by monks from Scotland and Ireland.

Soon all of England was Christian, but they did not stop there, instead choosing to return to Europe, the place their ancestors had come from. Many missionaries, especially from the northern kingdom of Northumbria travelled to the kingdoms of Frisia and Saxony to spread the gospel. While some were allowed to build churches and tend to congregations, others were less lucky like the monk Boniface who met his end at the hands of zealous pagans in the Frisian town of Dokkum where he was clubbed to death.

Creation of England

Empty fifteenth-century tomb of King Æthelstan at Malmesbury Abbey

The Anglo-Saxons created the English nation. The word England is a compound of “Angle” and “land”, meaning “land of the Angles.” Before the arrival of the Vikings from Scandinavia, the Anglo-Saxons had lived in small kingdoms like Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex, without having a single king to rule over them all. However in AD. 865 the Vikings amassed a “Great Heathen Army” and took over the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms one by one, until only Wessex remained. A king Alfred fought against the invaders for decades, at one point even being forced to flee his capital at Winchester, and was forced to take refuge in the marshes of Somerset in the far west of England.

While fighting against the Vikings Alfred saw how weak the separate kingdoms had been and came up with the idea of one nation of “Englaland”, one nation with one king and under one god. Alfred’s kingdom remained free for the rest of his life, although it would be up to his grandson Athelstan who finally became king of England in AD.

Mercenaries

After being defeated by the Normans in 1066, many Anglo-Saxons left Britain and sailed to modern-day Constantinople to fight for the Byzantium Empire. The Varangian Guard was an elite military unit set up by the Byzantine Empire in 874 AD as a personal guard for Emperor Michael III. Initially the unit had been made up of Swedish Vikings who’d sailed down the rivers of Russia and Ukraine, but after the Norman Conquest increasing numbers of Anglo-Saxon Englishmen joined the elite unit to fight against the enemies of the Last Roman Empire in the east. In 1088, 235 English and Danish ships sailed to Byzantium to join the Varangian Guard, which soon changed its name to “Englinbarrangoi” or “Anglo-Varangian”.

The Last Anglo-Saxon King was Buried in 1984

The last Anglo-Saxon king was buried in 1984. In AD. 975, a 15 year old named Edward was crowned king of England upon the death of his father Edgar.

Other Articles you Might Like

23 Fascinating Anglo-Saxon Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About!

The Old English or the Anglo-Saxon period of history begins the long journey of a nation which we now know as England.

The term England came from the Anglo-Saxons as they were the Angles and subsequently the place where they resided was named ‘the land of the Angles.’ The reign of the Anglo-Saxons continued for almost 600 years from 450 AD to October 14, 1066.

The Anglo-Saxons remained in England between the Romans went away and the Normans invaded the country. People from Scandinavia migrated to Britain, taking up their own areas to look after.

A number of tribes arrived from various parts of Europe after the Roman army left Britain. These tribes formed the Anglo-Saxons. Most of the people were farmers who were searching for some new land to grow crops as floodwater had made it impossible to farm in their homeland. They built a new empire, rich in culture. The map of Britain was changed permanently during the Anglo-Saxon period. Many of the names of the places are still in use today such as Sussex and Essex. The people were fond of merriment and they spent a major part of the night in the celebration by drinking and feasting.

If you like this article and enjoy going through it, do not forget to check out similar articles on Anglo-Saxon coins facts and Anglo-Saxon church facts.

Why did the Anglo-Saxons invade Britain?

A number of factors led to the Anglo-Saxons invading Britain in the fifth century. The first invasion was attempted during the fourth century but was halted by the Roman army.

About a hundred years later in 450 AD, Britain was left by the Ancient Romans, creating an opportunity for outsiders to invade the nation. The outsiders came from various parts of Europe belonging to the tribes of Anglo, Saxon, and Jute. Anglo and Saxon were the largest of the three and this is how the name ‘Anglo-Saxons’ came to be. The tribes were full of fierce people and often fought one another. A strong warrior ruled over each tribe and look after their people.

A sixth-century monk, Gildas, is of the opinion that Saxon tribes were employed to protect Britain after the Roman army left. Hence, the Anglo-Saxons were invited as immigrants. Some centuries later, another monk, Bede, writes that these immigrants were quite powerful. The British were ruled over by someone named Vortigern. During a conference between British nobles and Anglo-Saxons in 472 AD, hidden knives were used by the Anglo-Saxons to murder the British. Vortigern did not lose his life but he had to give away some huge parts of Britain to the tribals. He was now a ruler in name, only working as a puppet for the Anglo-Saxons.

What was Anglo-Saxon life like?

The Anglo-Saxon era was a culturally rich period with its own religion, beliefs, and language.

The Old English people made their houses out of wood having thatched roofs. The excavation of the houses shows that the people practiced some prehistoric version of open plan living. Maximum houses consisted of only a single room. There was no need for more rooms as the people ate, slept, and did their job in one location. The chief of the village lived in the largest house which housed his warriors beside him. It included a long hall having a stone fire near the middle portion. From the walls hung battle armor and hunting trophies. The walls had tiny windows with a hole near the roof that allowed the smoke to escape.

The Romans had left behind stone houses and roads but it was not liked by the Anglo Saxons. They were searching for a place with plenty of natural resources such as water, food, and wood. The forests of Britain were like providence to them. Agriculture was the most important source of livelihood for the people.

In the early parts of the Old English age, the people were pagans and different gods were worshipped by them, the chief being Woden. They had various gods for different things including weather, war, family, and agriculture. The people were superstitious in nature. They had faith in lucky charms and magic spells. Even the thought of dragons was real for them. A number of Christian traditions that are in practice today have come from the Old English period, although they were not part of Christianity.

St. Augustine was sent to Britain by the Pope in AD 597. The aim of St. Augustine was to convert the Anglo-Saxons living in the nation into Christians. The first Old English king who turned to Christianity was King Ethelbert of Kent.

The chief of the tribe gave their name to the early villages to let everyone know about the person who is in charge. The immigrants settled in various corners of the nation – the Angles in East Anglia, the Jutes in Kent, and the Saxons in Middlesex, Sussex, Wessex, and Essex (whether they lived in the middle, the south, the west, or the east. Some of the chiefs understood the advantage of walled cities and they erected their wooden houses enclosed in the stone walls left by Romans.

The people loved to eat and make merry. The chief would often host large feasts in his hall for the villagers. The Anglo-Saxon society liked to party. They cooked their meat on the fire, drank beer, ate bread, and sang songs late into the night. Barley, oats, and wheat were grown along with vegetables like carrots and parsnips.

The clothes worn by the Anglo-Saxons were made by themselves out of natural items. The males used linen or wool to make long-sleeved tunics which were often decorated with patterns. Woolen trousers were worn under the tunic which was held in place by leather belts. The belts had utility as they could be used to hang the tools required such as pouches and knives. The shoes were created of leather and tied up with toggles and laces. The Anglo-Saxon women used to wear an under-dress made of wool or linen as well as an outer dress such as a pinafore named ‘peplos’. This was attached with the underlayer with the help of two brooches at the shoulders. The women were fond of jewelry and they sometimes wore beaded necklaces, rings, and bracelets.

What language did the Anglo-Saxons speak?

The modern English language has come from the evolution of the Anglo-Saxon language or the Old English language.

To the people who know Modern English, the Old English language might seem like a totally different language. The epic poem Beowulf was written in the Anglo-Saxon language and remains one of the most well-known epics of the world. The language spoken by the inhabitants of England during this time was Welsh, which is a Celtic language.

The names of various places in modern England have come from their original Anglo-Saxon ones. The name provides hints regarding the original settlement of the people. Such as — ‘wich’ meaning farm and ‘ingham’ meaning village. From this clue, you can understand that an Anglo-Saxon village existed where Birmingham now stands and Norwich was supposed to be a farm in the Old English age.

Some of the names of days we use in a week have their origin in the Anglo-Saxon period. Monday comes from ‘Monandoeg’ while Wednesday is derived from ‘Wodnesdoeg’. The Anglo-Saxon gods inspired some of the names such as ‘Wodnesdoeg’ that is named after the god Woden.

The Anglo-Saxons used most of the letters that can be found in the Modern English alphabet. The exceptions being j, q, and v not a part while the letters z and k were used very rarely. Three extra letters were used by the Anglo-Saxons.

When was the Anglo-Saxon period?

The Anglo-Saxon period extended for 600 years from the fifth century to the 11th century.

The Old English age began when Romans left Britain in 410 AD. The Picts smashed Hadrian’s wall in 367 AD. The warlike tribes coming from Germany settled in Britain after some battles. The various tribes ignited a fire in southern Britain near the middle of the fifth century. From this onslaught, Britain gained a new leader in the form of Ambrosius Aurelianus.

Around 500 AD, a battle took place at Mount Badon or Mons Badonicus that was probably located somewhere near the southwest region of modern England. The Britons handed a huge loss to the Saxons.

The Vikings made several attempts to invade Britain beginning from 793 AD. They looted and destroyed villages and towns along the coastline of Britain. They settled in parts of the nation and renamed York to Jorvik. The Anglo-Saxon King of Wessex, Alfred the Great, was successful in stopping the Viking invasion. He is one of the most important kings of England who wanted the best for his subjects. The armies of Britain became stronger under him. Alfred the Great started the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to record annual events. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is the most significant source of the history of England. He knew the importance of good education and was responsible for the translation of Latin texts into Old English so that the local people could understand them.

King Edgar was among the most powerful kings of the nation as of yet. His son Edward was murdered by the grooms of his half-brother Aethelred in AD 978. His body was exhumed and subject to rebury in 979 AD. It was rediscovered in 1931 and finally, in 1984 he got a proper burial.

The Battle of Hastings in 1066 AD was a turning point in the history of England. The Anglo-Saxon King Edward passed away without an heir. King Harold II was chosen as the ruler but this was opposed by William the Conqueror hailing from Normandy and the Norwegian King Harald Hardrada. William brought his army to Britain and thus began the Battle of Hastings. Harold was executed and William became the first Norwegian to rule Britain as King William I. When Harold died, Edgar Atheling was officially declared as the king but he never wore the crown.

Which were Anglo-Saxon countries?

The country that is known as England, came much later after the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in Britain.

A total of seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms existed among the conquered areas of Britain. These were Northumbria, Essex, East Anglia, Mercia, Wessex, Kent, and Sussex. Each of these countries was ruled by an Anglo-Saxon king and asserted their independence fiercely. The nations had similar features in the form of pagan religions, cultural and socioeconomic ties, and similar languages. But the people were highly loyal to their Anglo-Saxon kings and did not trust anyone coming from another nation of Anglo-Saxon Britain. The seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were collectively called Heptarchy and all of them wanted to dominate the remaining six. The first Anglo-Saxon king to rule over all of Anglo-Saxon England was Egbert in AD 802.

Here at Kidadl, we have carefully created lots of interesting family-friendly facts for everyone to enjoy! If you liked our suggestions for 23 fascinating Anglo-Saxon facts you probably didn’t know about!, then why not take a look at Anglo-Saxon food or Vikings and Anglo-Saxons facts?

10 little-known facts about the Anglo-Saxons |

10 They May Have Built An ‘Apartheid’ Society

Photo Source: EttuBruta

there are so many Germanic men in England today.

Two years after the study hit the British press, it was challenged by John Pattison of the University of South Australia at Mawson Lakes. According to Dr. Pattison, the idea that a small number of elite Germanic warriors managed to defeat their British rivals downplays the fact that Germanic tribes and native Britons intermarried for generations prior to fifth-century invasions.

9 Anglo-Saxon Culture Was Nearly Eradicated

Before they were defeated by the Normans after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, another group of Vikings (Danes) nearly destroyed Anglo-Saxon culture. Beginning in the ninth century, after years of raiding the coast, the Danish Vikings began to settle in Britain and establish small but powerful communities. In 851 the Danish army spent the winter at their seat at Thanet, and later a force of about 350 ships attacked Canterbury and London before being defeated by the West Saxon army.

This early defeat did not stop. Danes because they kept pouring into the island. They became farmers and fearsome warriors, which in turn brought them political power.

For their part, the Anglo-Saxons, who by this point were fully Christian, regarded the pagan Danes as basically pagans. a separate race of demons controlled by Satan himself. Although both groups were culturally and genetically similar to each other, these religious differences helped perpetuate a cycle of violence that would last well into the 11th century.

8 Anglo-Saxon Rulers Oversaw A Pogrom

Although the term is most closely associated with 20th century European horrors, pogroms, organized massacres of certain ethnic or religious groups were not uncommon in the ancient world . In fact, on November 13, 1002, Anglo-Saxon England itself became the scene of a brutal campaign of ethnic terror.

On that day the English king Ethelred the Incapable, whose brother had been killed many years ago at Corfe Castle, issued an order to kill all Danish settlers in England.

King Æthelred’s actions earned him the eternal hatred of the Danish crown. By 1013 King Sweyn I of Denmark was named King of England after Æthelred fled to Normandy. Swain died less than a year later, and Æthelred’s advisors sought his return as king. However, due to the evil blood and feud caused by King Æthelred, Canute, son of King Sweyn, was busy destroying the Anglo-Saxon village in his own pogrom.

7 Anglo-Saxon Christianity Was Nearly Destroyed By A Pagan King

Photo source: Violetriga

During the first decades of the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain, the Anglo-Saxons, who were pagans, massacred the native Christian population.

In 628, King Penda established his political supremacy after defeating the Saxon kingdom of Khvichche at the Battle of Cirencester. After the victory, Penda not only annexed the territory of the Khwichche, but also, together with the Welsh leader Cadwallon of Gwynedd, invaded the powerful kingdom of Northumbria and killed the Christian king Edwin in 632. This victory not only made the Kingdom of Mercia the most powerful. throughout England, but it also helped paganism briefly supplant Christianity as the religion of choice among the Anglo-Saxons.

Although King Penda was known for his barbarism and cruelty, he did not completely abolish Christianity in his kingdom.

6th Blood Month