Anglo saxon fun facts: Top 10 Facts about The Anglo-Saxons — Fun Kids

Posted onThe Anglo-Saxons: Facts & Information for Kids

Who Were the Anglo-Saxons?

The Anglo-Saxons were invaders, particularly of Germanic origins, that began to take over and control England beginning in 449 A.D. and ending during the Norman Conquest in 1066 A.D. The Anglo-Saxons primarily consisted of the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Frisians, and Franks.

In the early 5th century, the Roman Empire was falling so troops were withdrawn from the British Isles. The Romans left Britain with roads, buildings, some forms of Christianity, and political disarray. Native tribes lacked unity and were weak to attacks by other tribes or outsiders.

When Roman left Britain, northern inhabitants (Picts and Scots) of the isle began attacking those in the south. At the same time, Angles, Saxons, and Jutes began invading British towns. Unable to defeat the northern Picts and Scots, some southern towns reached out to the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes for assistance.

The Germanic invaders did push back the Picts and Scots, but the Anglo-Saxons began to fight for land to establish their own kingdoms.

Harold Godwinson was King of the Anglo-Saxons. He was killed in the Battle of Hastings when the Normans invaded.

Where Did They Come From?

The Anglo-Saxons are primarily considered Germanic, and came from the areas of continental Europe, such as modern Germany and Denmark.

The Angles came from Denmark. They came from Angulus, a district in Schlewswig. They primarily settled in Mercia, Northumbria, and Anglia during Germanic invasions of England.

The Saxons migrated to Britain from Northern Germany. Today, the area would be considered near the North Sea coast spanning the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark.

Historians are unsure as to the origin of the Jutes, because there is really no record of the Jutes in continental Europe. Their language suggests that they came from the Jutland peninsula.

The Frisians came from regions near the Rhine at Katwijk. Primarily, they were from coastal regions of the Netherlands.

When Did the Anglo-Saxons Exist?

The Anglo-Saxons primarily existed between 410 A.D. and 1066 A.D.

What is the Difference Between the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings?

There are several differences between the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings, and the two groups of people adamantly fought each other for the control of Britain.

While the Anglo-Saxon’s homeland was primarily situated in the Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium, and Germany, The Vikings came from Scandinavia. This means the Vikings had their homelands in Norway, Sweden, and some parts of Denmark.

Britons during this period referred to the Vikings as the “Northmen” because they primarily came from northern homelands.

The Vikings were also considered pagans, while the Anglo-Saxons had further developed a form of Christianity. Vikings raided monasteries and attacked towns.

What is the Difference Between Saxons and the Normans?

While the Normans came from Northern France, specifically Normandy, to overthrow the Anglo-Saxons and any Viking rule, the Normans were originally Vikings from areas of Scandinavia.

The French king at the time, Charles II, gave land to a Viking chief (named Rollo) as a sign of peace between the French and the Vikings. The Vikings in Normandy lost their Viking customs, farmed the land in Normandy, became Christian, and assimilated into French society. Later, in 1066, the Norman-French army began the Norman Conquest, defeating the Anglo-Saxon army in Britain.

The Normans were Vikings that adopted French culture and then assisted with the Norman Conquest.

Read more about the Norman Conquest

- They differentiated between two people with the same name by adding either the place the person came from of the job the person did: therefore, Baker, Fisher, and Weaver are all originate from Anglo-Saxon naming systems.

- Anglo-Saxons believed in fighting to avenge deaths and to end feuds

- The only way to end a feud without fighting was to either pay money or arrange a marriage.

- Kings are known as “ring-givers,” which means the king gives out spoils of war to his warriors.

- The worst fate for an Anglo-Saxon warror was to be exiled, outlive his warrior friends, or live longer than the king.

- Anglo-Saxons primarily had an oral culture

- Anglo-Saxons used “kennings” which are phrases consisting of compound metaphors. For instance, “whale-road” refers to the sea.

- East Anglian kings were called Wuffings

Cite this article as: «The Anglo-Saxons: Facts & Information for Kids,» in History for Kids, September 29, 2022, https://historyforkids.org/the-anglo-saxons-facts-information-for-kids/.

References

- Delahoyde, Michael.

“Anglo-Saxon Culture.” Washington State University. https://www.uta.edu/english/tim/courses/4301f98/oct12.html

- Morris, Tim. “Anglo-Saxon England.” University of Texas at Arlington. https://www.uta.edu/english/tim/courses/4301f98/oct12.html

Everything You Need To Know About The Anglo-Saxons

Here, Martin Wall brings you 10 facts about the Anglo-Saxons…

1

Where did the Anglo-Saxons come from?

The people we call Anglo-Saxons were actually immigrants from northern Germany and southern Scandinavia. Bede, a monk from Northumbria writing some centuries later, says that they were from some of the most powerful and warlike tribes in Germany.

Bede names three of these tribes: the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. There were probably many other peoples who set out for Britain in the early fifth century, however. Batavians, Franks and Frisians are known to have made the sea crossing to the stricken province of ‘Britannia’.

The collapse of the Roman empire was one of the greatest catastrophes in history. Britain, or ‘Britannia’, had never been entirely subdued by the Romans. In the far north – what they called Caledonia (modern Scotland) – there were tribes who defied the Romans, especially the Picts. The Romans built a great barrier, Hadrian’s Wall, to keep them out of the civilised and prosperous part of Britain.

As soon as Roman power began to wane, these defences were degraded, and in AD 367 the Picts smashed through them. Gildas, a British historian, says that Saxon war-bands were hired to defend Britain when the Roman army had left. So the Anglo-Saxons were invited immigrants, according to this theory, a bit like the immigrants from the former colonies of the British empire in the period after 1945.

Listen: Susan Oosthuizen explains why we should be reassessing what we think about the Anglo-Saxons

2

The Anglo-Saxons murdered their hosts at a conference

Britain was under sustained attack from the Picts in the north and the Irish in the west.

More like this

It is possible that Vortigern was the son-in-law of Magnus Maximus, a usurper emperor who had operated from Britain before the Romans left. Vortigern’s recruitment of the Saxons ended in disaster for Britain. At a conference between the nobles of the Britons and Anglo-Saxons, [likely in AD 472, although some sources say AD 463] the latter suddenly produced concealed knives and stabbed their opposite numbers from Britain in the back.

Treaty of Hengist and Horsa with Vortigern. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

Vortigern was deliberately spared in this ‘treachery of the long-knives’, but was forced to cede large parts of south-eastern Britain to them. Vortigern was now a powerless puppet of the Saxons.

3

The Britons rallied under a mysterious leader

The Angles, Saxons, Jutes and other incomers burst out of their enclave in the south-east in the mid-fifth century and set all southern Britain ablaze.

It has been postulated that Ambrosius was from the rich villa economy around Gloucestershire, but we simply do not know for sure. Amesbury in Wiltshire is named after him and may have been his campaign headquarters.

A great battle took place, supposedly sometime around AD 500, at a place called Mons Badonicus or Mount Badon, probably somewhere in the south-west of modern England. The Saxons were resoundingly defeated by the Britons, but frustratingly we don’t know much more than that. A later Welsh source says that the victor was ‘Arthur’ but it was written down hundreds of years after the event, when it may have become contaminated by later folk-myths of such a person.

Gildas does not mention Arthur, and this seems strange, but there are many theories about this seeming anomaly. One is that Gildas did refer to him in a sort of acrostic code, which reveals him to be a chieftain from Gwent called Cuneglas.

- Read more | Hereward the Wake: the Anglo-Saxon rebel who became William the Conqueror’s nemesis

4

Where did the Anglo-Saxons settle?

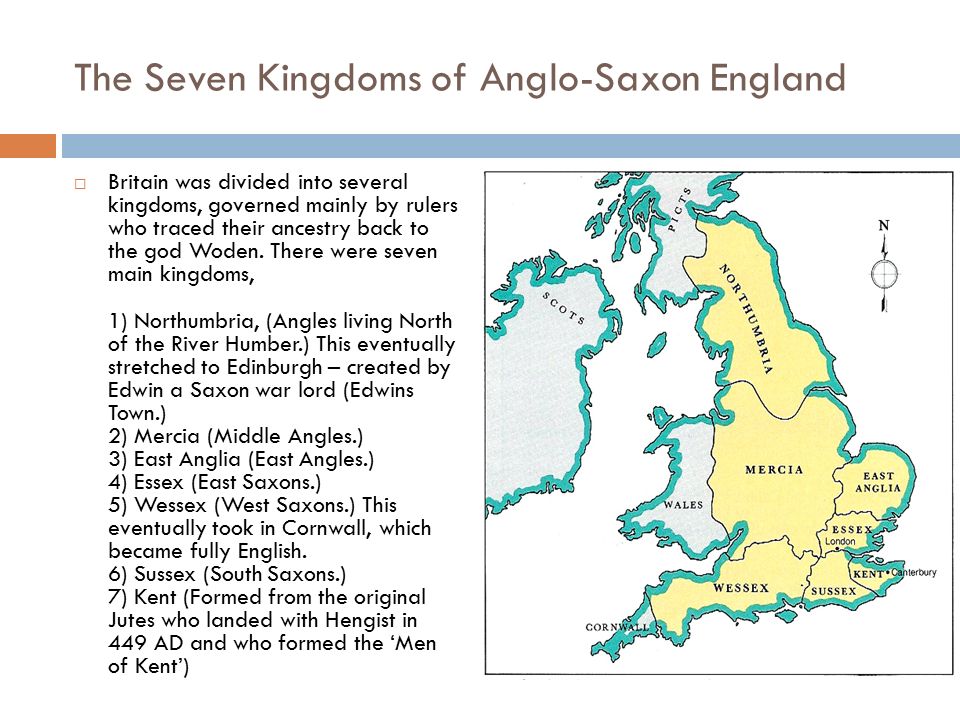

‘England’ as a country did not come into existence for hundreds of years after the Anglo-Saxons arrived. Instead, seven major Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were carved out of the conquered areas: Northumbria, East Anglia, Essex, Sussex, Kent, Wessex and Mercia. All these nations were fiercely independent, and although they shared similar languages, pagan religions, and socio-economic and cultural ties, they were absolutely loyal to their own kings and very competitive, especially in their favourite pastime – war.

- Read more | A brief history of England

Shield of Mercia, from the Heptarchy; a collective name applied to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of south, east, and central England during late antiquity and the early Middle Ages.

At first they were pre-occupied fighting the Britons (or ‘Welsh’, as they called them), but as soon as they had consolidated their power-centres they immediately commenced armed conflict with each other.

Woden, one of their chief gods, was especially associated with war, and this military fanaticism was the chief diversion of the kings and nobles. Indeed, tales of the deeds of warriors, or their boasts of what heroics they would perform in battle, was the main form of entertainment, and obsessed the entire community – much like football today.

Listen: Professor Stephen Rippon explores the changing nature of England’s landscape, from the Iron Age until the Anglo-Saxon period

5

Who was in charge?

The ‘heptarchy’, or seven kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons, all aspired to dominate the others.

Eventually a leader from Mercia in the English Midlands became the most feared of all these warrior-kings: Penda, who ruled from AD 626 until 655. He personally killed many of his rivals in battle, and as one of the last pagan Anglo-Saxon kings he offered up the body of one of them, King Oswald of Northumbria, to Woden. Penda ransacked many of the other Anglo-Saxon realms, amassing vast and exquisite treasures as tribute and the discarded war-gear of fallen warriors on the battlefields.

This is just the sort of elite military kit that comprises the Staffordshire Hoard, discovered in 2009. Although a definite connection is elusive, the hoard typifies the warlike atmosphere of the mid-seventh century, and the unique importance in Anglo-Saxon society of male warrior elites.

- Read more | A closer look at the Staffordshire Hoard

6

Which religion did Anglo-Saxons follow?

The Britons were Christians, but were now cut off from Rome, but the Anglo-Saxons remained pagan.

St Augustine of Canterbury, who was sent by Pope Gregory to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. St Augustine is seen here preaching before Ethelbert, Anglo-Saxon King of Kent. Augustine was the first Archbishop of Canterbury. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

One reason why they converted was because the church said that the Christian God would deliver them victory in battles. When this failed to materialise, some Anglo-Saxon kings became apostate, and a different approach was required. The man chosen for the task was an elderly Greek named Theodore of Tarsus, but he was not the pope’s first choice. Instead he had offered the job to a younger man, Hadrian ‘the African’, a Berber refugee from north Africa, but Hadrian objected that he was too young.

- Read more | Prehistoric religion: a pagan riddle we will never solve?

The truth was that people in the civilised south of Europe dreaded the idea of going to England, which was considered barbaric and had a terrible reputation. The pope decided to send both men, to keep each other company on the long journey. After more than a year (and many adventures) they arrived, and set to work to reform the English church.

Theodore lived to be 88, a grand old age for those days, and Hadrian, the young man who had fled from his home in north Africa, outlived him, and continued to devote himself to his task until his death in AD 710.

7

Alfred the Great had a crippling disability

When we look up at the statue of King Alfred of Wessex in Winchester, we are confronted by an image of our national ‘superhero’: the valiant defender of a Christian realm against the heathen Viking marauders. There is no doubt that Alfred fully deserves this accolade as ‘England’s darling’, but there was another side to him that is less well known.

Alfred never expected to be king – he had three older brothers – but when he was four years old on a visit to Rome the pope seemed to have granted him special favour when his father presented him to the pontiff. As he grew up, Alfred was constantly troubled by illness, including irritating and painful piles – a real problem in an age where a prince was constantly in the saddle. Asser, the Welshman who became his biographer, relates that Alfred suffered from another painful, draining malady that is not specified. Some people believe it was Crohn’s Disease, others that it may have been a sexually transmitted disease, or even severe depression.

The truth is we don’t know exactly what Alfred’s mystery ailment was. Whatever it was, it is incredible to think that Alfred’s extraordinary achievements were accomplished in the face of a daily struggle with debilitating and chronic illness.

- Read more | Are we whitewashing the truth about Alfred the Great?

8

An Anglo-Saxon king was finally buried in 1984

In July 975 the eldest son of King Edgar, Edward, was crowned king.

Edward the Martyr, Anglo-Saxon king of England and the elder son of King Edgar, c975 AD. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

One day in 978, Edward decided to pay Elfrida and Aethelred a visit in their residence at Corfe in Dorset. It was too good an opportunity to miss: Elfrida allegedly awaited him at the threshold to the hall with grooms to tend the horses, and proffered him a goblet of mulled wine (or ‘mead’), as was traditional. As Edward stooped to accept this, the grooms grabbed his bridle and stabbed him repeatedly in the stomach.

Edward managed to ride away but bled to death, and was hastily buried by the conspirators.

Edward’s body was exhumed and reburied at Shaftesbury Abbey in AD 979. During the dissolution of the monasteries the grave was lost, but in 1931 it was rediscovered. Edward’s bones were kept in a bank vault until 1984, when at last he was laid to rest.

Listen: Historian Marc Morris tackles some of the most common misconceptions about the Anglo-Saxon era

9

England was ‘ethnically cleansed’

One of the most notorious of Aethelred’s misdeeds was a shameful act of mass-murder. Aethelred is known as ‘the Unready’, but this is actually a pun on his forename. Aethelred means ‘noble counsel’, but people started to call him ‘unraed’ which means ‘no counsel’. He was constantly vacillating, frequently cowardly, and always seemed to pick the worst men possible to advise him.

One of these men, Eadric ‘Streona’ (‘the Aquisitor’), became a notorious English traitor who was to seal England’s downfall. It is a recurring theme in history that powerful men in trouble look for others to take the blame. Aethelred was convinced that the woes of the English kingdom were all the fault of the Danes, who had settled in the country for many generations and who were by now respectable Christian citizens.

On 13 November 1002, secret orders went out from the king to slaughter all Danes, and massacres occurred all over southern England. The north of England was so heavily settled by the Danes that it is probable that it escaped the brutal plot.

One of the Danes killed in this wicked pogrom was the sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, the mighty king of Denmark. From that time on the Danish armies were resolved to conquer England and eliminate Ethelred. Eadric Streona defected to the Danes and fought alongside them in the war of succession that followed Ethelred’s death.

10

Neither William of Normandy or Harold Godwinson were rightful English kings

We all know something about the 1066 battle of Hastings, but the man who probably should have been king is almost forgotten to history.

Edward ‘the Confessor’, the saintly English king, had died childless in 1066, leaving the English ruling council of leading nobles and spiritual leaders (the Witan) with a big problem. They knew that Edward’s cousin Duke William of Normandy had a powerful claim to the throne, which he would certainly back with armed force.

William was a ruthless and skilled soldier, but the young man who had the best claim to the English throne, Edgar the ‘Aetheling’ (meaning ‘of noble or royal’ status), was only 14 and had no experience of fighting or commanding an army. Edgar was the grandson of Edmund Ironside, a famous English hero, but this would not be enough in these dangerous times.

So Edgar was passed over, and Harold Godwinson, the most famous English soldier of the day, was chosen instead, even though he was not, strictly speaking, ‘royal’.

- Read more | Why is Harold Godwinson a hero of the Bayeux Tapestry?

A huge Viking army landed and destroyed an English army outside York. Harold skilfully marched his army all the way from the south to Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire in a mere five days. He annihilated the Vikings, but a few days later William’s Normans landed in the south. Harold lost no time in marching his army all the way back to meet them in battle, at a ridge of high ground just outside… Hastings.

Martin Wall is the author of The Anglo-Saxon Age: The Birth of England (Amberley Publishing, 2015). In his book, Martin challenges our notions of the Anglo-Saxon period as barbaric and backward, to reveal a civilisation he argues is as complex, sophisticated and diverse as our own.

This article was first published by HistoryExtra in 2015

Anglo-Saxon KS2 Facts for Kids — PlanBee

Who was in Britain after the Romans left? Who did the Vikings raid and battle within Britain?

The Anglo-Saxons inhabited Britain for almost 600 years! Read on to find out more about them and what life was like in the Dark Ages!

Where did the Anglo-Saxons come from?

Anglo-Saxons came from many places all over Europe including Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands. They were known at the time as Jutes, Angles and Saxons. They lived in Britain between 410 AD and 1066 AD settling in the country after the Romans left following the collapse of the Roman Empire.

A map of Anglo-Saxon origins

Where did Anglo-Saxons live?

Upon their arrival in Britain, the Anglo Saxons began to battle the Britons left behind by the Romans for land, farms and villages to live in. The Britons moved north and west into areas that are now Wales, Devon, Cornwall and Northern England.

An Anglo-Saxon house

Most people lived in houses made of wood, often built over a shallow cellar. They were rectangular in shape and were mainly just one or two rooms. They heated their homes with open fires in hearths, usually in the middle of the floor. There were no chimneys so smoke escaped gradually through the thatched roofs.

An Anglo-Saxon farmer

Most people earned their living on the land as farmers but there were craftsmen who worked with leather, wood, pottery, glass and other materials to make shoes, furniture, pots, pans, belts, jewellery and other objects. These were usually men. There were no large cities, no schools and no formal law system. There were no doctors yet either. Some people earned their living travelling from place to place as jugglers, jesters or musicians.

What did Anglo-Saxons eat?

Anglo-Saxons ate what they could grow, harvest, rear and catch. Cows, pigs, chickens and geese were raised and many other wild animals were caught to be eaten.

Anglo-Saxons drank beer and a fermented drink made from honey called mead. They didn’t drink water as the river water was usually very polluted. Weak beer was drunk by everyone, including children. Milk was available if the family kept cows. Stronger beer was saved for feasts and special occasions. Wine was only available for the very rich.

What did the Anglo-Saxons wear?

Anglo-Saxon clothes were often made from wool that could be taken from their sheep. Men wore trousers and long tunics and women usually wore long dresses known as ‘peplos’.

Anglo-Saxon clothing

What did the Anglo-Saxons do?

In their free time, many Anglo-Saxon villages would come together and tell stories. This was an important learning opportunity for younger members of the village and people enjoyed telling stories to each other. One famous story that we know of from this time period is the story of Beowulf: A powerful warrior who conquered the foul creature Grendel.

The original Beowulf manuscript

Looking for Beowulf resources for your class? Click here!

KS2 Anglo Saxons, Picts and Scots FREE Beowulf Story Freebee

When not telling stories, people would play music and sing together or they would play board games such as Merels or Tabula.

Who were the Anglo-Saxons?

There were strict ranks in Anglo-Saxon Britain.

Laws were harsh in Anglo-Saxon times. Liars had their tongues cut out and thieves had their hands chopped off. Sometimes, a criminal was given a trial by ordeal, such as holding a red-hot iron. If the wound was healed, they were declared innocent. ‘Weregild’ was paid as compensation if you injured someone or did wrong to someone. The amount of ‘weregild’ paid depended on how important the victim was. Jails had not yet been invented as a form of punishment and neither had guillotines, but hanging was introduced to Britain during the Anglo-Saxon era and became one of the most widely used punishments.

Anglo-Saxons did not understand what caused diseases but they tried their best to cure them.

What did Anglo-Saxons believe?

When the Anglo-Saxons first came to Britain, they brought their beliefs in gods, goddesses and religion with them. However, in AD 597, Pope Gregory, the leader of the Christian church, sent a missionary to England. After that, more and more people became Christians and the Anglo-Saxons started building churches. However, many people held on to their traditional beliefs and mixed them with Christianity. An example of this is the Christian celebration of Easter. This got its name from the pagan goddess of spring: Eostre. In springtime, pagans would feast and celebrate the new year. This became mixed with the Christian festivities to celebrate Jesus’ resurrection.

Eostre goddess of Spring

Despite the growing popularity of Christianity in England at this time, the Anglo-Saxons still practised some of their pagan festivities and rituals.

What happened to the Anglo-Saxons?

In the year 793 AD Vikings from Norway, Denmark and Sweden first raided a monastery in Lindisfarne on the northeast coast of England. At this time there were seven separate kingdoms across England.

Anglo-Saxon kingdom map 793 AD

Over the next 100 years, Viking raids became more and more common, with the Vikings eventually beginning to settle in England and create villages of their own. They were powerful warriors and in 865 AD a huge army arrived in England conquering massive areas of North and East England. It took them only thirteen years to occupy a third of England. This area became known as Danelaw.

Anglo-Saxon kingdom map 886 AD

After many violent battles the king of Wessex, King Alfred, brokered a peace treaty in 886 AD with the Viking king, Guthrum.

In 1016, the Anglo-Saxon king Edmund died. He left the kingdom to the Viking king Cnut. The kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia and Danelaw were now under the control of a single king. Cnut also ruled Denmark and much of Norway. He was a very powerful king.

When Cnut died in 1035, there was a disagreement about who should be his successor. This resulted in several years of war. Eventually Edward the Confessor became king in 1042. England became very powerful during his reign. He ordered that Westminster Abbey (a huge cathedral) be built in London, beginning in 1050. This magnificent piece of architecture still stands today!

Unfortunately, when King Edward died in 1066 there was another argument about who his successor should be.

Contenders for the English throne

There were many battles, most famously the Battle of Hastings in October 1066. Both Harolds were killed during these battles and William the Conqueror of Normandy and his Norman army were victorious. Thus ended the Anglo-Saxon and Viking era and Norman Britain began.

Find out more about the Battle of Hastings using these FREE Fact Cards for KS2.

More Interesting Anglo-Saxon Facts:

- The period of time after the Romans left Britain is sometimes known as the Dark Ages. This is because much of the advancements in technology the Romans brought with them was lost and Britain pretty much returned to how it was before the Romans invaded and settled there.

-

The names Essex, Sussex and Wessex are derived from the name Saxon and a compass direction.

South Saxons = Sussex, East Saxons = Essex and West Saxons = Wessex.

- Some of our modern English words, such as the days of the week, come from the Anglo-Saxon language (sometimes called Old English).

- Much of what we know about the Anglo-Saxons comes from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

- King Alfred was the first to call the people living in his kingdom Englishmen.

- There were tribes of people living in Scotland at the time called Picts and Scots.

- The Battle of Hastings is depicted in a famous tapestry called the Bayeux Tapestry.

Life in Anglo-Saxon England — Local Histories

By Tim Lambert

Society in Anglo-Saxon England

Everyday life in Anglo-Saxon England was hard and rough even for the rich. Society was divided into three classes. At the top were the thanes, the Saxon upper class. They enjoyed hunting and feasting and they were expected to give their followers gifts like weapons.

In early Anglo-Saxon Times England was a very different place from what it is today. It was covered by forest. Wolves prowled in them and they were a danger to domestic animals. The human population was very small. There were perhaps one million people in England at that time. Almost all of them lived in tiny villages – many had less than 100 inhabitants. Each village was mainly self-sufficient. The people needed only a few things from outside like salt and iron. They grew their own food and made their own clothes.

By the 11th century, things had changed somewhat. The great majority of people still lived in the countryside but a significant minority (about 10%) lived in towns.

The Anglo-Saxons also gave us most English place names. Anglo-Saxon place name endings include ham, a village or estate, tun (usually changed to ton), a farm or estate, hurst, a wooded hill, and bury, which is derived from the Anglo-Saxon word burh, meaning fortress or fortified settlement. The Anglo-Saxons called groups of Roman buildings a caester. In time that world evolved into the place name ending chester, caster or cester.

Kinship (family ties) were very important in Anglo-Saxon society. If you were killed your relatives would avenge you. If one of your relatives was killed you were expected to avenge them. However, the law did provide an alternative. If you killed or injured somebody you could pay them or their family compensation. The money paid was called wergild and it varied according to a person’s rank.

At first, Anglo-Saxon society was relatively free. There were some slaves but the basis of society was the free peasant. However, in time Anglo-Saxon churls began to lose their freedom. They became increasingly dependent on their Lords and under their control.

Farmers in Anglo Saxon England

The vast majority of Anglo-Saxons made their living from farming. Up to 8 oxen pulled plows and fields were divided into 2 or sometimes 3 huge strips. One strip was plowed and sown with crops while the other was left fallow. The Anglo-Saxons grew crops of wheat, barley, and rye. They also grew peas, cabbages, parsnips, carrots, and celery. They also ate fruit such as apples, blackberries, raspberries, and sloes. They raised herds of goats, cattle and pigs, and flocks of sheep.

However, farmers could not grow enough food to keep many of their animals through the winter so as winter approached most of them had to be slaughtered and the meat salted.

Some Anglo-Saxons were craftsmen. They were blacksmiths, bronze smiths, and potters. At first, Anglo-Saxon potters made vessels by hand but in the 7th century, the potter’s wheel was introduced. Other craftsmen made things like combs from bone and antler or horn. There were also many leather workers and Anglo-Saxon craftsmen also made elaborate jewelry for the rich.

Homes in Anglo-Saxon England

The Anglo-Saxons lived in wooden huts with thatched roofs. Usually, there was only one room shared by everybody. (Poor people shared their huts with animals divided from them by a screen. During the winter the animal’s body heat helped keep the hut warm). Thanes and their followers slept on beds but the poorest people slept on the floor.

There were no panes of glass in windows, even in a Thane’s hall and there were no chimneys. Floors were of earth or sometimes they were dug out and had wooden floorboards placed over them. There were no carpets. Rich people used candles but they were too expensive for the poor.

Food in Anglo-Saxon England

Anglo-Saxon women ground grain, baked bread, and brewed beer. Another Anglo-Saxon drink was mead, made from fermented honey. (Honey was very important to the Anglo-Saxons as there was no sugar for sweetening food. Bees were kept in every village). Upper-class Anglo-Saxons sometimes drank wine. The women cooked in iron cauldrons over open fires or in pottery vessels. They also made butter and cheese.

Anglo-Saxons ate from wooden bowls. There were no forks only knives and wooden spoons. Cups were made from cow horns. The Anglo-Saxons were fond of meat and fish. However, meat was a luxury and only the rich could eat it frequently. Ordinary people usually ate a dreary diet of bread, cheese, and eggs.

Clothes in Anglo-Saxon England

Saxon clothes were basic. Saxon men wore a shirt and tunic. They wore trousers like garments called breeches. Sometimes they extended to the ankle but sometimes they were shorts. Men might wear wool leggings held in place by leather garters. They wore cloaks held in place by brooches.

Saxon women wore a long linen garment with a long tunic over it. They also wore mantles. However Saxon women did not wear knickers.

Both men and women used combs made of bone or antler.

Rich Anglo Saxons

Rich people’s houses were rough, crowded, and uncomfortable. Even a Thane’s hall was really just a large wooden hut although it was usually hung with rich tapestries. Thanes also like to show off any gold they owned. Any furniture must have been simple and heavy such as wooden chests.

However, at least the rich Anglo-Saxons ate well.

Towns in Anglo-Saxon England

At first, the Anglo-Saxons were farming people and they had no need for towns. However in time trade slowly increased and some towns appeared. By the mid-7th century, the Anglo-Saxons were minting silver coins. In Anglo-Saxon times a new town of London emerged outside the walls of the old Roman town. Some towns were created deliberately. King Ine founded Southampton at the end of the 7th Century. Other towns grew up at Hereford, Ipswich, Norwich, and Bristol.

In the late 9th century and early 10th century, Saxon kings created fortified settlements called burhs. These were more than just forts. They were also flourishing little market towns.

King Alfred

Nevertheless, all these towns were very small by modern standards. In 1086 the population of London was only 16,000-18,000 and a large town like Lincoln only had 5,000 inhabitants. A medium-sized town like n had about 2,500 inhabitants. Many towns were smaller.

The old Roman towns fell into decay and Roman roads became overgrown. Travel was slow and dangerous in Anglo-Saxon times and most people only traveled if it was unavoidable. If possible people travelled by water along the coast or along rivers.

Last revised 2022

Anglo-Saxons Facts, Worksheets & Historical Background For Kids

Worksheets /Social Studies /World History /Anglo-Saxons Facts & Worksheets

Premium

Not ready to purchase a subscription? Click to download the free sample version Download sample

Table of Contents

Anglo-Saxons are people who reigned in Britain for approximately six centuries, from 410 AD to 1066 AD.

See the fact file below for more information on the Anglo-Saxons or alternatively, you can download our 25-page Anglo-Saxons worksheet pack to utilise within the classroom or home environment.

Key Facts & Information

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

- The Anglo-Saxons were no strangers to Britain, having served in the Roman army on the island.

- They began slowly colonizing Britain even before the Roman legions left. Despite this, historical evidence suggests that they were invited with the intention of defending the country from invasion.

- Following the departure of the Roman legions, Germanic-speaking Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians spontaneously showed up in Britain.

- They started out as small groups of invaders, but their numbers quickly grew.

- Despite their defenselessness, the people of Britain responded immediately with firm resistance.

- However, the invaders were firmly rejected by the Romano-British around 500 AD.

- Even so, in the mid-sixth century, a British Christian leader named Ambrosius, now known as “Arthur,” mobilized the Romano-British against the invaders.

- The writings of the monk Gildas were held up as solid evidence for this, along with Ambrosius’ victory in twelve battles during the rally.

- After successfully invading Britain, the Anglo-Saxons were divided into groups that settled in various parts of the country.

- They formed several kingdoms, which frequently changed and were constantly at odds with one another. These kingdoms occasionally recognized one of their rulers, the Bretwalda, as a “High King.”

THE ANGLO-SAXON KINGDOMS

- By the year 650 AD, the groups of Anglo-Saxons agreed to the distinction under seven kingdoms.

- Kent was formed as a result of the Jutes’ settlement. St. Augustine converted the very first Anglo-Saxon king, Ethelbert of Kent, to Christianity around 595 AD.

- Mercia was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom that spanned the Midlands between Wales and England. This large kingdom was famous for the Offa’s Dyke, which was built by its most famous ruler, Offa.

- Northumbria is the kingdom where the Ecclesiastical History of Britain was written by its dweller, the monk Bede.

- The famous Sutton Hoo ship burial was found in East Anglia. The Angles ruled the kingdom.

- Essex or East Saxons is where the famous Battle of Maldon was fought against the Vikings in 991.

- The South Saxons established the kingdom of Sussex.

- Wessex or the West Saxons was later referred to as King Alfred’s kingdom. King Alfred was the only English king to be referred to as “The Great.” His outstanding grandson, Athelstan, was the first to claim the title “King of the English.”

KING ALFRED THE GREAT

- King Alfred, a king of the kingdom of Wessex, earned the title of being “the Great” due to various reasons.

- In 878, he led his troops to victory over the Vikings at the Battle of Edington.

As a result of this, he was able to retake London from the Vikings.

- He was successful in establishing boundaries between the Saxons and the Vikings. The Viking-dominated region was known as the Danelaw.

- His kingdom’s defenses were strengthened by the construction of a series of fortresses (burhs) and a strong army.

- He also pioneered the English navy as he constructed ships against the sea attacks from the Vikings.

- King Alfred recognized the importance of education. For this reason, he even translated some books into English.

- He commissioned the writing of a historical record of the Anglo-Saxons in Britain, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

- When the Vikings stormed Lindisfarne Monastery in 793, the Anglo-Saxons’ history became intertwined with the Vikings’. They were similar in many ways, including language, religious belief, and Northern European ancestry, but they were not the same. The fact that they infiltrated Britain at varying periods distinguishes them as two distinct groups of people in our history.

ANGLO-SAXONS IN POETRY

- Some English poems offered fascinating insights into the Anglo-Saxons.

- Beowulf is the story of a great hero who fought and killed the monster Grendel and his mother, rose to become a great king, and died in a battle with an outraged dragon.

- The Ruin is an untraceable poem about the decay and ruin of a Roman town.

- The Battle of Maldon is a poem about the Saxons’ valiant defense against a looting Viking force in Essex.

Anglo-Saxons Worksheets

This is a fantastic bundle which includes everything you need to know about the Anglo-Saxons across 25 in-depth pages. These are ready-to-use Anglo-Saxons worksheets that are perfect for teaching students about the Anglo-Saxons who are people who reigned in Britain for approximately six centuries, from 410 AD to 1066 AD. The period of their invasion is also recognized as the Dark Ages, owing to the scarcity of references for the initial periods of the Saxon uprising.

Complete List Of Included Worksheets

- United Kingdom Anglo-Saxons Facts

- Ang-Look Saxon

- Anglo-gy Test

- The Great Inspiration

- King-dom Map

- Venn Diagram

- Historical Treasure

- Draw the Helmet

- Fill in the Beo-lanks

- The Poet in You

- Brought-tain

Link/cite this page

If you reference any of the content on this page on your own website, please use the code below to cite this page as the original source.

<a href=»https://kidskonnect.com/history/anglo-saxons/»>Anglo-Saxons Facts & Worksheets: https://kidskonnect.com</a> — KidsKonnect, June 4, 2021

Link will appear as Anglo-Saxons Facts & Worksheets: https://kidskonnect.com — KidsKonnect, June 4, 2021

Use With Any Curriculum

These worksheets have been specifically designed for use with any international curriculum.

Games and Pastimes of the Anglo-Saxons

An early Boogie-Woogie

Bugle Boy from Company B

All cultures, regardless of how arduous the times they live in, have some kind of sport, games, and pastimes to engage in during leisure hours, and thankfully children have always played. In Anglo-Saxon times (roughly 450 CE to 1100 CE) life was largely lived outdoors for most people, for the continuance of life was predicated on agricultural labour. The interiors of most buildings were dark, smoky, and often cramped, and many tasks whether for livelihood or leisure required the clear strong light of daylight.

Children played with many more natural objects than they do today; a later medieval sermon, which still holds true for the Anglo-Saxon era, mentions children playing

“with flowers…with sticks, and with small bits of wood, to build a chamber, buttery, and hall, to make a white horse of a wand, a sailing ship of broken bread, a burly spear from a ragwork stalk, and of a sedge a sword of war, a comely lady from cloth, and be right busy to deck it elegantly with flowers.

” (G.R. Owst, Literature and Pulpit in Medieval England, Oxford, 1961)

Grave finds from early heathen burials contain carved wooden toys such as horses and small wooden boats, tenderly laid to rest with their little owner. But childhood was short for the Anglo-Saxon girl or boy, and girls of five or six were already spending part of their day learning to spin wool, to card fleece, or help with the younger children in the family. Boys tended animals or helped in the fields. Boys also played with small spears and knives carved of wood, learning the arts of hunting and defense at a young age.

Miniature tools sized for a child’s hand have been found, much like children’s sized gardening implements today, but since a child would be more useful at an activity such as egg gathering or sheep tending perhaps such tools were meant as playthings rather than actual implements of labour for young hands. (Although no one pulls weeds better than an industrious six year old.

Sometimes for adults work and play were mingled. In some villages plough races were held by the men on Plough Monday, the first Monday after Twelfth Night (Epiphany), the end of the Yuletide season.

Not your average little piggy

Physical fitness was obviously of paramount importance to people of all classes – life was hard and demanding, and being physically able to cope with the realities of farming, tree-felling, and of course, battle, could mean the literal difference between life and death. Young men in particular held foot-races, participated in wrestling matches, and practiced the martial arts such as spear throwing, archery, and mock sword play. Those who were rich enough to own horses would have raced them to see whose was the fastest; the Old English epic Beowulf mentions young men doing just that:

“The warriors let their bay horses go/a contest for the best horse/galloping through whatever path looked fair.” (David Breeden translation)

Hunting was not purely sport, as it was relied upon to bring food to the table, but it could be very exciting and therefore enjoyable.

Good hounds were cherished both as working animals and as companions, and the rich often times made gifts of such dogs. King Ælfred, greatest king of the Anglo-Saxon era and perhaps indeed of any other, sent a brace of fine hounds to the archbishop of Reims.

Nice doggie…nice doggie…down doggie!

Only the very richest lords kept falcons specially trained to bring down pigeons and starlings and the like. Riding out on horseback and releasing the falcon and watching it swoop down on its prey was a very aristocratic sport indeed.

Although most fish were captured in weirs set up in rivers, streams, and narrow ocean channels, line fishing was practiced, and was undoubtedly found to be as enjoyably frustrating as it is today.

The Anglo-Saxons had a great love of ornament on even everyday objects, and men and women spent long hours decorating the spines of wood, bone, and horn hair combs with drawings of animals, embellishing gowns and tunics with gaily coloured embroidery, and decorating leather goods by stamping them with metal dies and burning designs into the surface with heated pokers. The most utilitarian of items such as wooden buckets and dippers generally carried some decoration, even if only simple incised lines or dots around the perimeter.

Darn, broke the teeth again….

Many of these handcrafts would have been practiced out of doors to take advantage of the good light.

Indoor pastimes included a variety of board games that used little clay and carved markers, and games using dice. Just as today almost everybody enjoyed such pastimes, and our modern word “game” comes from the Old English “gamen”. Dice games were very popular (so popular that even clergy played them) and many die have been found. Betting played a large role in dice games, just as it does today.

The game of tæfl was played on a board using game pieces in opposition. The rules of early games probably varied quite a bit, but many of these games featured a piece which represented the “king” which needed to be protected by the other pieces.

Tæfl Board:Care to wager?

The stunning contents of a grave of an Anglo-Saxon prince or king (possibly of King Sabert who died in 616 CE) discovered near Southend in Essex in 2003 and known as the Prittlewell Find contained 57 gaming pieces carved of bone and two very large dice carved from antler. This shows us that games were important enough in the lives of the Anglo-Saxons that they accompanied their owners into the afterlife.

In the latter Anglo-Saxon period, from the 12th century onward, chess (a particular favourite of my own), originally created in India, was brought to Britain. With its war lords, warriors, and horsemen it echoed the battle-driven lives of the noblemen and women who played it. Two forms of chess were played, one quite similar to the challenging intellectual game we know today, and one simplified version which employed dice, and thus introduced an element of luck.

Sutton Hoo Harp: Meant for

an early Jimi Hendrix

Storytelling, singing and dancing were also part of the long indoor Winter evenings. Harps such as the beautiful one buried with the Sutton Hoo treasure (the burial goods of a great king from about 625 CE, now on display at the British Museum) were played by professional story tellers called scops, but small hide drums, wood pipes and whistles are easily made from everyday materials and were probably played by a wide variety of children and adults. Listening was an active art, and when the professional storyteller or scop began his tale, all turned attentively to him and listened raptly, picturing in their mind’s eye the great heroes, battles, hunts, and religious episodes he sang of.

The love of word-play extended to riddles, and close to one hundred riddles of the Anglo-Saxon period have been recorded in The Exeter Book, a manuscript written about 975, and still kept at Exeter Cathedral Library. Here is one:

“A creature came slinking where men were sitting, many of them in council, men shrewd in mind. It had one eye and two ears and two feet, twelve hundred heads, a back and a belly and two hands, arms and shoulders, one neck and two sides. Say what I am called.” (S.A.J. Bradley translation)

I wish I could Shimmy like my sister Kate…

Can you guess it? The answer is: A one eyed garlic seller.

There was also pleasure to be taken in the simple contemplation of unspoilt nature. A 14th century treatise on the duties and pleasures of a nobleman lists “Watching the snow fall” as an act worthy of his rank, and indeed during Winter when many agricultural duties were suspended and war rarely waged one can also imagine his earlier forbears doing the same.

Curious facts from the history of the English monarchy. (1): glebminskiy — LiveJournal

The myth of «Good Old England» that arose in the Middle Ages is still widely rooted. How old is England? If we take a conditionally traditional countdown from the Norman Conquest in 1066, then it is not very old. Even the traditions of the Russian monarchy are more ancient, conditionally traditional counting from 862. Well, if you delve into the previous Anglo-Saxon era, then perhaps it’s “old”, the date of the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon conquest of Britain is 449the year when the semi-legendary leaders of the Germanic Jutes Hengist and Horza landed in Kent at the invitation of the High British King Vortigern. There are other «intermediate» dates. But «good» England was hardly. Especially if you look at her attitude towards her monarchs. Let’s take the period from 1066 to 1714, that is, from the Norman Conquest to the establishment on the throne of the Kingdom, the German Hanoverian dynasty, a branch of the famous Second House of Welf, descended from the Italian margraves of Oberting.

Speaking of dynasties, or rather their origins. We have fierce disputes about the origin of the Ruriks. They descended from Obodrite (Slavic) princes from Rurik-Rarog Bodritsky, or from the king of the Norman-Vikings (Germans) Khrerik of Jutland. (There are, by the way, other versions, more exotic — Hunnic-Bulgarian, Turkic-Khazarian and Sarmatian-Alano-Bosporan, but about them later). And for some reason, the first is considered patriotic, and the second is not. As for me, so what’s the difference, in any case, they became Russified and became quite RUSSIAN! Like later the Holstein-Gottorps of Oldenburg, who became truly Russian tsars and emperors of the Romanovs! Moreover, at that time there was no such thing as an ethnos or a nation, and people thought more in generic categories. But the British do not bother with this, after 1066 they did not have a single purely «English» dynasty, and yet all monarchs are considered truly English.

However, let’s get back to our sheep, that is, directly to the kings. Well, with Willy the Bastard, sorry, William the Conqueror, everything is clear. Incredible bastard! A bastard who became a duke, and who first defeated the internal opposition in Normandy, and then external opponents in the person of King Henry I of France and the powerful and militant Count of Anjou, Geoffroy II Martel.

Death of Wilhelm II Rufus.

The son and heir of William I the Conqueror, King of England William II Rufus (Red, Red-faced), having corrected 13 years, died on a hunt.

The death of the White Ship.

Queen Matilda.

Stephen was only 6 years old, when during the Crusade to Palestine in 1102 his father, Etienne (Stefan), also died in the battle of Ramal, his mother Adela, the daughter of William the Conqueror, sent him to her brother Henry I. Stephen was raised in the Norman spirit at the court of his uncle, and when he died, he took the throne of England, with the support of part of the Anglo-Norman nobility and clergy. However, his cousin Matilda, the daughter of Henry, did not recognize this and put forward her claims to the throne. The entire reign of Stephen was filled with wars with his opponents, and received the name «Anarchy» in English historiography.

Stefan Bloissky and Heinrich Plantagenet discusses over the River Thamza issues of the throne of the throne in the English kingdom

Anglo -Saxon period

The Commonwealth of four nations

nations, which are the basis of the foundation the last millennium, which was largely facilitated by the historical division of the state into four provinces. The unification of four distinctive ethnic groups into a single nation of the British became possible due to a number of reasons.

During the period of great geographical discoveries (XIV-XV centuries), a powerful unifying factor for the population of the British Isles was the reliance on the national economy. It helped in many ways to overcome the fragmentation of the state, which, for example, was in the lands of modern Germany.

Britain, unlike European countries, due to geographic, economic and political isolation found itself in a situation that contributed to the consolidation of society.

An important factor for the unity of the inhabitants of the British Isles was religion and the formation of a universal English language associated with it.

One more peculiarity appeared during the period of British colonialism – it is an accentuated opposition between the population of the metropolis and the native peoples: “There are us, and there are they”.

Until the end of World War II, after which Britain ceased to exist as a colonial power, separatism in the Kingdom was not so clearly expressed. Everything changed when a stream of migrants poured into the British Isles from the former colonial possessions — Indians, Pakistanis, Chinese, residents of the African continent and the Caribbean.

It was at this time that the growth of national identity in the countries of the United Kingdom became more active. Its climax came in September 2014, when Scotland held its first independence referendum.

The trend towards national isolation is confirmed by the latest sociological surveys, in which only a third of the population of Foggy Albion identified themselves as British.

How did the Anglo-Saxons live?

Up until the 9th century, the majority was represented by communal peasants who owned large plots of land. Curls had full rights, could take part in public meetings, and carry weapons.

After the Danish pogrom of the 870s, Alfred the Great re-established the kingdom in much the same way as it had done for the Germanic tribes living on the Continent. The king is at the head of the state. The tribal nobility were the closest relatives. Queens also had good privileges. The king himself was surrounded by close associates and retinue. From the latter, the service and flax nobility were gradually formed.

In the literature, much attention is paid to the clothes in which people walked. Women wore long, loose dresses that fastened at the shoulders with large buckles. Characteristic in those days was jewelry in the form of brooches, necklaces, pins and bracelets. Men usually wore short tunics, tight-fitting trousers and warm raincoats.

The Anglo-Saxons used an alphabet consisting of 33 runes. With their help, they made all kinds of signatures on jewelry, dishes or bone elements. The Latin alphabet was adopted with the advent of Christianity, while some handwritten books from that time have survived to this day.

By nature, the Anglo-Saxons were fearless and cruel. Such traits formed a tendency to indiscriminate robbery. It was because of this that they were feared by other tribes. People despised danger. They launched their robber ships into the water and let the wind carry them to any overseas shore.

The reasons for the evolution of English law

The flexibility of the English legal system is demonstrated by its good adaptability to changing civilizational requirements:

- Until the 10th century, judicial practice was based mostly on the customs inherent in a particular locality, which is typical for the communal system.

- The emergence of the concept of precedent as a court decision in some case is evidence of the formation of feudal relations.

Democracy to the process was added by the participation of local jurors in royal visiting courts, which contributed to the establishment of common low. The introduction of statutes with broad powers of judges only strengthened the faith of society in the judicial system.

- At the stage of the birth of capitalist relations, there was a need to resolve disputes previously unknown to common law and without precedents (trade and financial). This is how the “right of justice” arose.

- With the further development of English society, it became possible to combine common low and Equity Low due to the accumulation of a sufficient base of precedents to successfully use them in judicial practice within one system.

- After the end of the colonial era, England changed the development paradigm, turning into a global financial player. The transfer of legislative powers to a number of ministries was required.

For hundreds of years, the features of the legal system have not changed radically.

« Money is being printed » now the Anglo-Saxons are in the USA. For this they have US Federal Reserve . The Fed masquerades as part of a government structure, but is in fact «private» and owned by individuals. Moreover, among these individuals there are probably guys of Jewish appearance. Symbiosis is not well understood and may be the subject of many studies. But it turns out that either the Jews were accepted into the ranks of the Anglo-Saxons, or the chosen people bought the Anglo-Saxons. I will not try to find out how they have it there specifically, not about that article.

In practice, everything looks like this — in theory, the Fed belongs to the United States, but in practice it is controlled by the Rockefeller clan.

The creation of money out of thin air and the functioning of the economies of the United States, Britain and a number of other Western countries are associated with constant debt and other financial bubbles , with constant lending and re-lending.

The appearance of the English

Having come to power, the new king brought his Norman elite to the island. French briefly became the language of the aristocracy and, in general, of all the upper classes. However, the old Anglo-Saxon dialect was preserved in a huge peasant environment. The gap between social strata did not last long.

Already in the 12th century, the two languages merged into English (an early version of the modern one), and the inhabitants of the kingdom began to call themselves English. In addition, the Normans brought with them the classical feudal system and the military fief system. So a new nation was born, and the term «Anglo-Saxons» became a historical concept.

Attention, only TODAY!

Share on social networks:

Operation Blood Eagle

British sources claim that the Normans agreed with the inhabitants of Kent and landed unhindered on the Isle of Thanet south of the Thames Estuary.

Northern sources add that Ivar the Boneless took possession of York in advance by cunning as a vira for the death of his father and won the favor of Ella, after which he secretly lured his commanders to him and convinced the brothers to launch an invasion. In York, he stocked up food in advance so that he could easily ride out the siege.

According to the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, in 866 the Northumbrians, led by King Ella, besieged the Vikings who had settled in York. They even managed to break into the city, but then military fortune betrayed the British — also because some of the soldiers of the king of Northumbria suddenly turned their swords on their own.

To take revenge on the killer of their father, they used the most terrible northern execution — the bloody eagle. According to Ragnarssona þáttr, Strands about the sons of Ragnar, «Ivar ordered to cut an eagle on Ella’s back, and then cut it with a sword along the ridge and tear out the insides so that the lungs were outside. The skalds dedicated the lines to this event:

And Ivar king, the ruler of Jorvik, commanded to cut Ella’s back along the ridge.

Gesta Danorum and Ragnars saga loðbrókar ok sona hans describe a more moderate variant. According to them, a specially found wood carving master just «carved Elle on the back of a beautiful eagle, and for greater atrocity, they sprinkled all this on top with salt and left the king to die.

Over the corpse of an enemy ruler, King Ivar the Boneless declared that he wanted to rule all of England.

After wintering in captured Northumbria, whose under-plundered inhabitants chose to acknowledge the invaders’ authority and pay tribute, the Vikings embarked on the next step of conquest.

Attacks of the Danes and Normans

Since 793, the invasion of the Vikings, mainly Danes, began. They even established themselves in Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia. Alfred, having defeated the Danes, concluded the Treaty of Wedmore with them, stopping their advance. His son, Edward the Elder and grandson, Æthelstan, expanded their dominions by military and diplomatic means, and Æthelstan became the first real ruler of all of England.

The country enjoyed the outside world until King Æthelred II the Unwise (978-1016), when the Danes resumed their attacks with even greater force. The country fell into a sorry state. In the provinces, the counts turned their regions into hereditary lands. The king had to pay off the Danes for a lot of money (the so-called Danish money), which was levied in the form of a land tax. Nevertheless, despite the constant ransom, huge crowds of foreigners remained in the country and seized land in the provinces. In order to immediately get rid of uninvited guests, Ethelred decided on an act that cost him the throne.

When Æthelred died in the city, Canute the Great, son of Sweyn, took possession of England and married Æthelred’s widow, Emma. His sons Harold Hare’s Paw (1035-1040) and Hardeknut (1040-1042) died childless, and the English nobles put Ethelred and Emma’s son, Edward the Confessor (1042-1066) on the throne.

Heptarchy

Having conquered England, the aliens formed not one state, but seven or eight (see Heptarchy):

- Kent, with Canterbury as its capital, populated chiefly by the Jutes;

- Sussex, or country of the South Saxons;

- Wessex, or the country of the West Saxons, the principal city of Winchester;

- Essex, or the land of the East Saxons;

- Northumbria, or country north of the River Humber;

- East Anglia divided into Norfolk (northern people) and Suffolk (southern people) and

-

Mercia, in the marshlands of Lincolnshire, inhabited predominantly by the Angles.

In addition, in the southwest, several possessions of native princes, such as Dumnonia and Cumbria (in the area of \u200b\u200bnow Wales), have been preserved.

Prior to r. Roman-Christian learning made very little progress in Britain, being constantly supplanted by Germanic-pagan elements. The Christianization of England began in Kent after King Ethelbert, married to Bertha, daughter of the Frankish king Charibert, himself was baptized by St. Augustine (), who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury. The beginnings of Christian literature soon arose, reaching a high degree of prosperity in Bede the Venerable’s Ecclesiastical History of the Anglian People.

Guillaume the bastard

Among all the bastards of that time, Guillaume seemed to be the lucky one. He was the only son of Robert of Norman, nicknamed the Devil, so he had no competitors at first glance.

Robert succeeded to the ducal throne after the death of his brother Richard.

Was Robert I married? Reliable data has not been preserved, but some sources claim that yes, but he did not get along with his wife and drove his wife back to his father. Did he have children in a legal marriage? The data has not been preserved, but there is reason to believe that his son, the Bastard, was very actively cleaning historical sources in his favor. Well, or his supporters, who knew how to read and write, fussed. And among his supporters were those who could and were interested (we will not point fingers at the papacy).

Guillaume’s mother was… as they would say today, a lady of the demimonde, a certain Arleta (although in those years the demimonde looked somewhat different than during the Belle Epoque, but its essence was the same — to supply aristocrats with mistresses). Where Robert picked her up is unknown, but she gave birth to that same Guillaume and, according to some reports, Adelaide of Norman.

Oh well, let’s leave these small details to historians, back to our bastard. Generally speaking, modern historians argue that in those years every Norman aristocrat was essentially a bastard, because church marriage, de, was rarely entered into, due to its indissolubility, and therefore, de … But history retained the title Bastard only for Guillaume, that kaka be hints that in all these arguments there are some exaggerations and inaccuracies.

One way or another, but in 1034, when Guillaume was 6 years old, his dad, Robert the Devil, appointed little Guillaume as his heir, married Arleta to his vassal Gerluin, Viscount of Conteville and dumped him on a pilgrimage to the city of Jerusalem, in the course of who died of natural causes. Indeed, in those days, a cut throat was a completely natural way of death. And Guillaume would have been lost in a crowd of other rogues catching their luck along the high roads (and most likely, he would also die a death quite natural for that time), but none other than the king of France showed an unexpected participation in his fate.

We must pay tribute. Guillaume was a brave warrior and a clever diplomat, he knew perfectly well when to use the sword and when to negotiate.

So he lived until 1066, when the events in the British Isles allowed him to lay his paw on the English throne.

However, after seeing how many things happened there and what was mixed up, I decided that enough was enough for today. So what about the Norman conquest of England, why it happened and how it happened, and most importantly — what effect it had (and still has) on the moral character of the British nobility and politics, well, to the heap — why the modern Anglo-Saxon nobility and the political elite has nothing to do with the Anglo-Saxons themselves, from the word in general, even genetically, we will talk in the next article.

British Genetic Code

Recent genetic research may provide new insights into both the ancestry of the British and the uniqueness of the four main nations of the Kingdom. Biologists from University College London examined a segment of the Y chromosome taken from ancient burials and concluded that more than 50% of English genes contain chromosomes found in northern Germany and Denmark.

According to other genetic examinations, approximately 75% of the ancestors of modern Britons arrived on the islands more than 6 thousand years ago.

So, according to Oxford DNA-genealogist Brian Sykes, in many respects modern Celts of the ancestry are connected not with the tribes of central Europe, but with more ancient settlers from the territory of Iberia, who came to Britain at the beginning of the Neolithic.

Other data of genetic studies carried out in Foggy Albion literally shocked its inhabitants. The results show that the English, Welsh, Scots and Irish are genetically identical in many respects, which deals a serious blow to the vanity of those who are proud of their national isolation.

Medical geneticist Stephen Oppenheimer puts forward a very bold hypothesis, believing that the common ancestors of the British about 16 thousand years ago arrived from Spain and originally spoke a language close to Basque.

The genes of the later «invaders» (Celts, Vikings, Romans, Anglo-Saxons and Normans), according to the researcher, were adopted only to a small extent.

The results of Oppenheimer’s research are as follows: the Irish genotype has only 12% uniqueness, the Welsh — 20%, and the Scots and the British — 30%.

The geneticist supports his theory with the works of the German archaeologist Heinrich Hörke, who wrote that the Anglo-Saxon expansion added about 250 thousand people to the two million population of the British Isles, and the Norman conquest even less — 10 thousand. So for all the difference in habits, customs and culture, the inhabitants of the countries of the United Kingdom have much more in common than it seems at first glance.

Normans

Generally speaking, in Europe of the early Middle Ages, all the Vikings were called so, so the Anglo-Saxons were also Normans. But it was precisely in French Normandy that a completely special, unhealthy situation developed. There, the Normans found themselves, on the one hand, in the minority among a rather motley and scattered population, and on the other hand, they turned out to be the most powerful and organized military force.

The Normans turned out to be occupiers in Normandy, albeit with a royal license, and therefore behaved like occupiers. In particular, it was they who were the first to build classical castles — small fortresses that could accommodate only the feudal lord’s family and his squad.

We also note an important point: if the Angles, Saxons and Jutes came from Denmark, then the French Normans were mostly from Norway, that is, they belonged to a completely different branch, as they liked to say in the III Reich, the Nordic race.

Literature

- Alexander Domanin. Mongol Empire of Genghisides. Genghis Khan and his successors

- Charles Patrick Fitzgerald. History of China

- Boris Alexandrovich Gilenson. History of ancient literature. Book 2. Ancient Rome

- Boris Alexandrovich Gilenson. History of ancient literature. Book 1. Ancient Greece

- Sergey Alekseev. Slavic Europe of the 5th–8th centuries

- Alexey Gudz-Markov. Indo-Europeans of Eurasia and Slavs

- A.N. Bokhanov, M.M. Gorinov.

History of Russia from the beginning of the 18th to the end of the 19th century

- A.N. Bokhanov, M.M. Gorinov. History of Russia from ancient times to the end of the 17th century

- Igor Kolomiytsev. Secrets of Great Scythia

- V.Ya. Petrukhin, D.S. Raevsky. Essays on the history of the peoples of Russia in antiquity and the early Middle Ages

- E. Bickerman. Seleucid State

- E. A. Menabde. Hittite Society

- A. Kravchuk. Sunset Ptolemies

- Vladimir Mironov. Ancient Civilizations

- Nikolay Nepomniachtchi, Andrey Nizovsky. 100 great treasures

- Konstantin Ryzhov. 100 Great Bible Characters

- Andrey Nizovsky. 100 great archaeological discoveries

- Valery Gulyaev. Sumer. Babylon. Assyria: 5000 years of history

- Michael Edwards. Ancient India. Life, religion, culture

- Jan Marek. In the footsteps of sultans and rajas

- Roman Svetlov. Great Battles of the East

- Malcolm Todd.

Barbarians. Ancient Germans. Life, religion, culture

- team of authors. Tamerlane. Epoch. Personality. Acts

- Georges Duby. The tripartite model, or the conception of medieval society about itself

- A. A. Svanidze. Medieval town and market in Sweden XIII-XV centuries

- M. A. Zaborov. An Introduction to the Historiography of the Crusades (Latin Historiography of the 11th-13th Centuries)

- T.D. Zlatkovskaya. The emergence of the state among the Thracians of the 7th-5th centuries. BC.

- Jan Burian, Bogumila Moukhova. Mysterious Etruscans

- Vadim Egorov. Historical geography of the Golden Horde in the XIII-XIV centuries.

- R.Yu. Pochekaev. Batu. Khan who was not Khan

- V. M. Zaporozhets. Seljuks

- M. V. Kryukov, M. V. Sofronov, N.N. Cheboksary. Ancient Chinese: problems of ethnogenesis

- M.A. Dandamaev. Political history of the Achaemenid state

- E. O. Berzin. Southeast Asia in the XIII-XVI centuries

- D.

Ch. Sadaev. History of ancient Assyria

- L.C. Vasiliev. Ancient China. Volume 3. Zhangguo period (V-III centuries BC)

- Alexey Gorbylev. Ninja: Martial Art

- James Wellard. Babylon. The Rise and Fall of Wonder City

- Carl Blegen. Troy and Trojans. Gods and Heroes of Ghost Town

- Gordon Child. Aryans. Founders of European Civilization

- Pierre-Roland Gio. Bretons. Sea Romance

- Emmanuel Anati. Palestine before the ancient Jews

- William Culican. Persians and Medes. Subjects of the Achaemenid Empire

- Malcolm College. Parthians. Followers of the Prophet Zarathustra

- Hilda Ellis Davidson. Ancient Scandinavians. Sons of the Northern Gods

- E.A. Thompson. Huns. Dread Warriors of the Steppes

- David Lang. Armenians. Creator People

- Isabelle Henderson. Picts. Mysterious Warriors of Ancient Scotland

- David M. Wilson. Anglo-Saxons. Conquerors of Celtic Britain

- Donald Harden.

Phoenicians. Founders of Carthage

- Terence Powell. Celts. Warriors and magicians

- N.N. Nepomniachtchi. 100 Great Mysteries of India

- Eric Schroeder. People of Muhammad. Anthology of Spiritual Treasures of Islamic Civilization

- Lev Gumilyov. End and start again. Popular lectures on ethnology

- Alexander Alexandrovich Khannikov. Technique: from antiquity to the present day

Notes

- Intermediate between the Gesites and the Curls in Wessex was a small group of descendants of the British nobility, whose wergeld was 600 shillings.

- The presence of a city court in the Anglo-Saxon period has not yet become one of the main features of an urban settlement.

-

The number of mints gives a rough idea of the population and economic role of each city. So, in London there were more than 20 mints, in York — 12, in Lincoln and Winchester — 8-9, in Chester — 8, in Oxford and Cambridge — 7, in Thetford, Gloucester and Worcester — 6, etc.

- Tait, J. The Medieval English Borough.

- When transferred to the boxland, the king retained the right to recruit soldiers for the fird and the right to demand that the peasants repair bridges and royal castles in the area.

- The main burden of paying «Danish money» fell on the lands of the bokland, exempted from paying food rent to the king.

- The practice of withholding court fines in favor of members of the nobility has been known since the time of King Offa.

- In reality, the number of hydes in a hundred in Southern England varied from 20 to 150. In Middle England, the sizes of a hundred were more uniform and actually corresponded to 100 hydes, which is explained by the fact that the hundred in Middle England was introduced from above as part of a policy of unification in the 10th century after the accession Mercia to Wessex.

-

Unlike in Wessex, in Mercia the county boundaries did not correspond to historical tribal areas.

- Stanton, F. Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford, 1973.

Alfred the Great

Gradually, the ethnic and linguistic boundaries between the Germanic tribes were completely erased. Many factors contributed to this: long life side by side, trade, dynastic marriages between ruling dynasties, etc. The Anglo-Saxons are a people that appeared in the 9th century on the territory of the seven kingdoms

An important part of the rallying of the population was its Christianization. Before moving to the island, the Angles and Saxons, like all Germans, were pagans and worshiped their own pantheon of deities.

King Ethelbert of Kent was the first to be baptized in 597. The ceremony was conducted by Saint Augustine of the Catholic Church. Over time, the new teaching spread throughout the Germanic population of Britain. Christians — that’s who the Anglo-Saxons are, starting from the 7th — 8th centuries. To the ruler of Wessex, Egbert, who ruled in 802 — 839years, managed to unite under his rule all seven kingdoms.

Litigation

The English court chooses the cases it will deal with. The consideration of the dispute may be refused, of which the plaintiff is notified.

If the claim is finally accepted, a preliminary hearing is scheduled with the obligatory presence of the prosecution.

Jurors are especially carefully selected, which can be challenged by both the plaintiff and the defendant.

The court itself takes place in an environment that can convey the essence of the dispute as fully as possible. You can use all sources of evidence — plans, graphs, tables, films, audio recordings, other visual explanations of the position being defended.

Several stages are considered in any process:

- Representation of the parties and disclosure of the essence of the case.

- Claimant’s statement.

- Respondent’s speech.

- Argument of the parties.

- Closing speeches of lawyers.

- Jury verdict.

- Announcement of the decision by the court.

The system of law in the Anglo-Saxon legal field attaches great importance to the procedure for examining the details of a case. Therefore, the trial can take years.

- Author: Vladimir

Rate this article:

(0 votes, average: 0 out of 5)

Share with friends!

United Kingdom ● History and some interesting facts

U nited Kingdom — a country hidden from civilization on an island.

Capital — Landan … is the capital of great brit. They say they shit exclusively on Russia, and this explains a lot for us. Great Britain is not England and vice versa. Although for a Russian person it is one and the same. The United Kingdom is England, Scotland, Wales, then they annexed Ireland, which is still in an incomprehensible limbo, literally and figuratively.

Flag and coat of arms of Great Britain.

The population of England is 84% of the total population of the UK. Flag and coat of arms of England. For some reason, the Russians think for three, although God himself ordered the British to do this.

Probably a shame when the name of your country was given by the Germans. England is so called in honor of the Angles — a Germanic tribe that, along with the Saxons and Jutes, migrated to the island of Great Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries AD. e. English is nothing more than a mixture of German, Dutch, Danish, French, Latin and Celtic.

The first mention of the Angles is in a work called «Germany», written in 98 AD. e. ancient Roman historian Tacitus.

Even in England there is Stonehenge in Wiltshire, allegedly built in about 2500 BC. e. Perhaps then something was, but what is worth now is a fake. It was built on a flat meadow in 1954.

I can’t edit the post about the construction of Stonehenge. The «Conflict Commission» does not allow me this, which claims that all the photos of this post are spam. How Stonehenge was built

The territory of modern England at the time of the invasion of Julius Caesar in 55 BC, like a century later, by the time of the capture by the emperor Claudius, was inhabited by Celtic tribes called the Britons. As a result of the capture, the entire southern part of the island (modern England and Wales) became part of the Roman Empire until its collapse in the 5th century AD. e.

Without the help of the Roman legions, Roman Britain could not resist the barbarian Germans for a long time.

Alfred the Great became the first king of England. At the end of the 8th century, the Vikings (the tribe of the Danes) began to attack England. They took over part of the territory. Alfred failed to defend his country and went into exile. But then he returned and concluded an agreement with the Vikings.

In 1066 England was conquered by the Normans under the leadership of William the Conqueror. The Anglo-Saxon population was completely ousted from the upper strata of society and survived only among the peasants, while the English language was almost ousted by French and miraculously survived. The English aristocracy fled to Scotland, which remained independent. South Wales was conquered by the Normans.

Tower of London — the historic center of London, one of the oldest buildings in England.

The Tower of London is one of the main symbols of Great Britain