Arctic habitat: Polar habitats | TheSchoolRun

Posted onThe Arctic | National Wildlife Federation

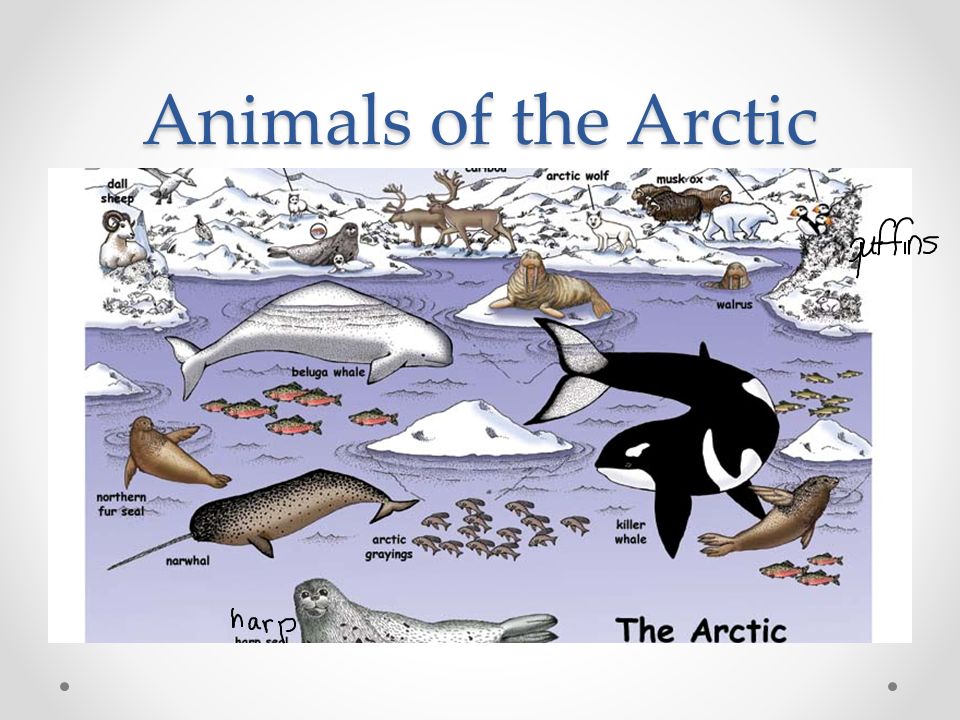

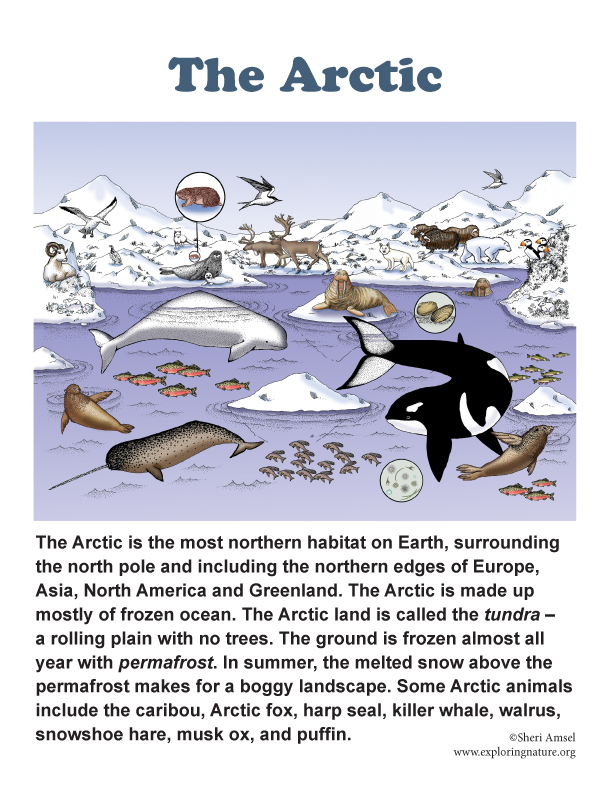

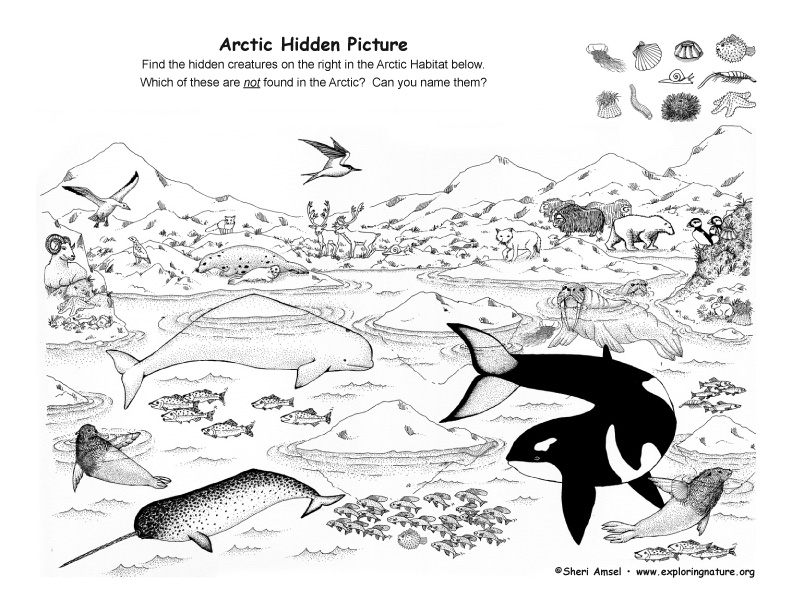

The Arctic is a region of extremes: extreme cold, extreme seasonal changes in daylight, and extreme winds. It sits at the top of world, covered in sea ice—a seemingly unwelcome place for life. Yet the Arctic is actually teeming with wildlife, from large mammals like walruses and polar bears to birds, fish, small plants, and even tiny ocean organisms called plankton.

The Arctic region covers much of Earth’s northern pole. The outer edge of the Arctic—which includes areas of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Russia—is made up of glaciers and tundra (treeless plains with frozen ground called permafrost). The central part of the Arctic (around the North Pole) is surrounded with large areas of sea ice.

Because of its polar location and the tilt of the Earth, the Arctic does not have the normal seasons that we are used to in the continental United States. An Arctic winter has days without sunlight, and the summer has days where the sun never sets (which is why it’s called the «land of the midnight sun»).

Throughout the year, temperatures can span a wide range. Average lows reach -40 degrees Fahrenheit in the winter and average highs reach 50 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer. A short growing season, permafrost, and long, dark winters of extreme cold and strong winds mean the Arctic is nearly treeless and only small plants can grow.

People

Although the Arctic is gaining popularity worldwide as a tourism and wildlife-watching destination, the region has always been vital to the identity, culture, and survival of its indigenous people. Tribes, such as the Gwich’in people of northeast Alaska and Canada’s northern Yukon and Northwest Territories, depend on the migratory caribou herds and the Arctic fisheries for food. The Yu’pik, Iñupiat, and Athabascan are also native groups to Alaska’s Arctic region. To adapt to the harsh climate, they developed warm dwellings and protective clothing. Many Arctic people now live with modern homes and appliances, however, there’s still a desire to pass on traditional knowledge and skills—such as hunting, fishing, herding, and native languages—to younger generations.

Wildlife

The Arctic is a unique ecosystem with a complex food web made up of organisms adapted to its extreme conditions. It is one of the most biologically productive ecosystems in the world, supporting many large fisheries and huge populations of migratory birds that come to the Arctic in the summer to breed.

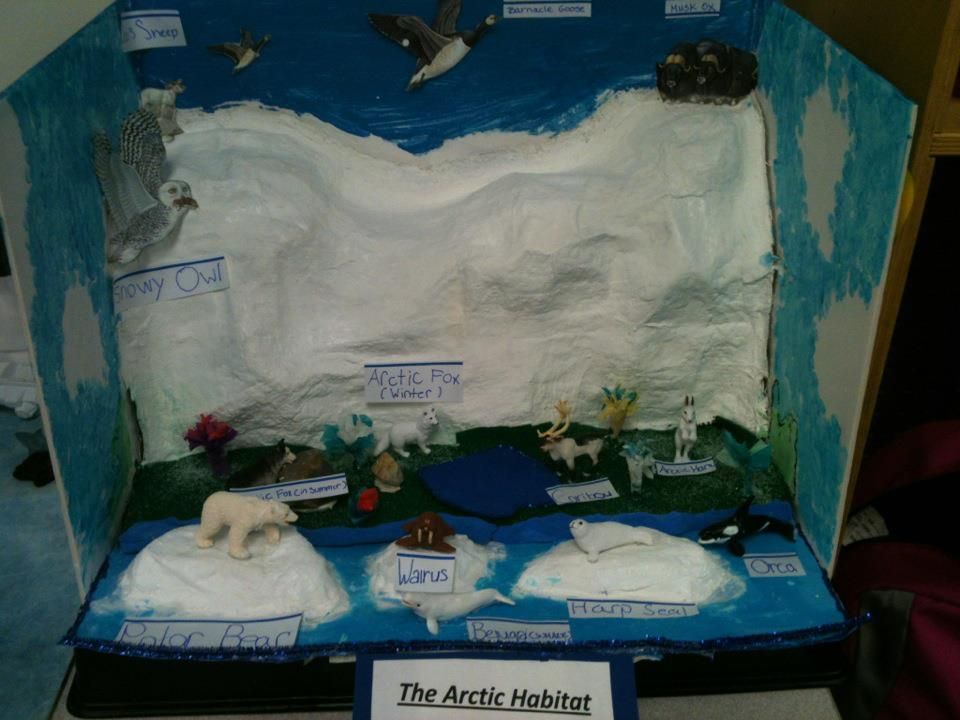

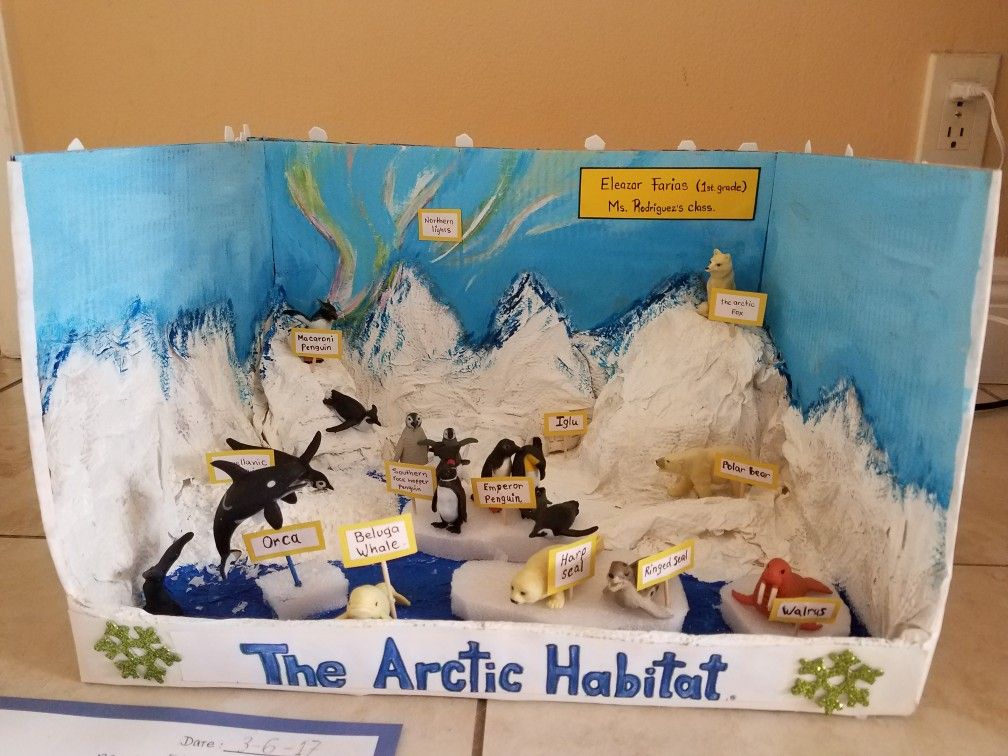

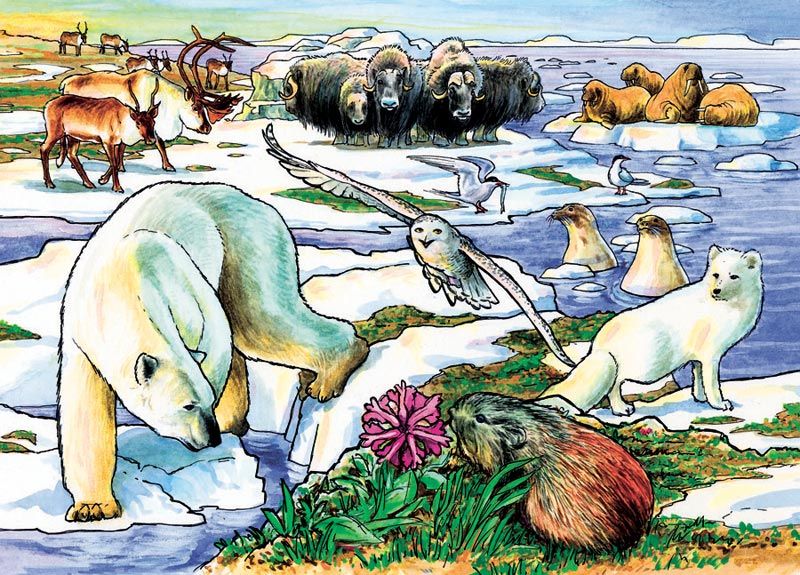

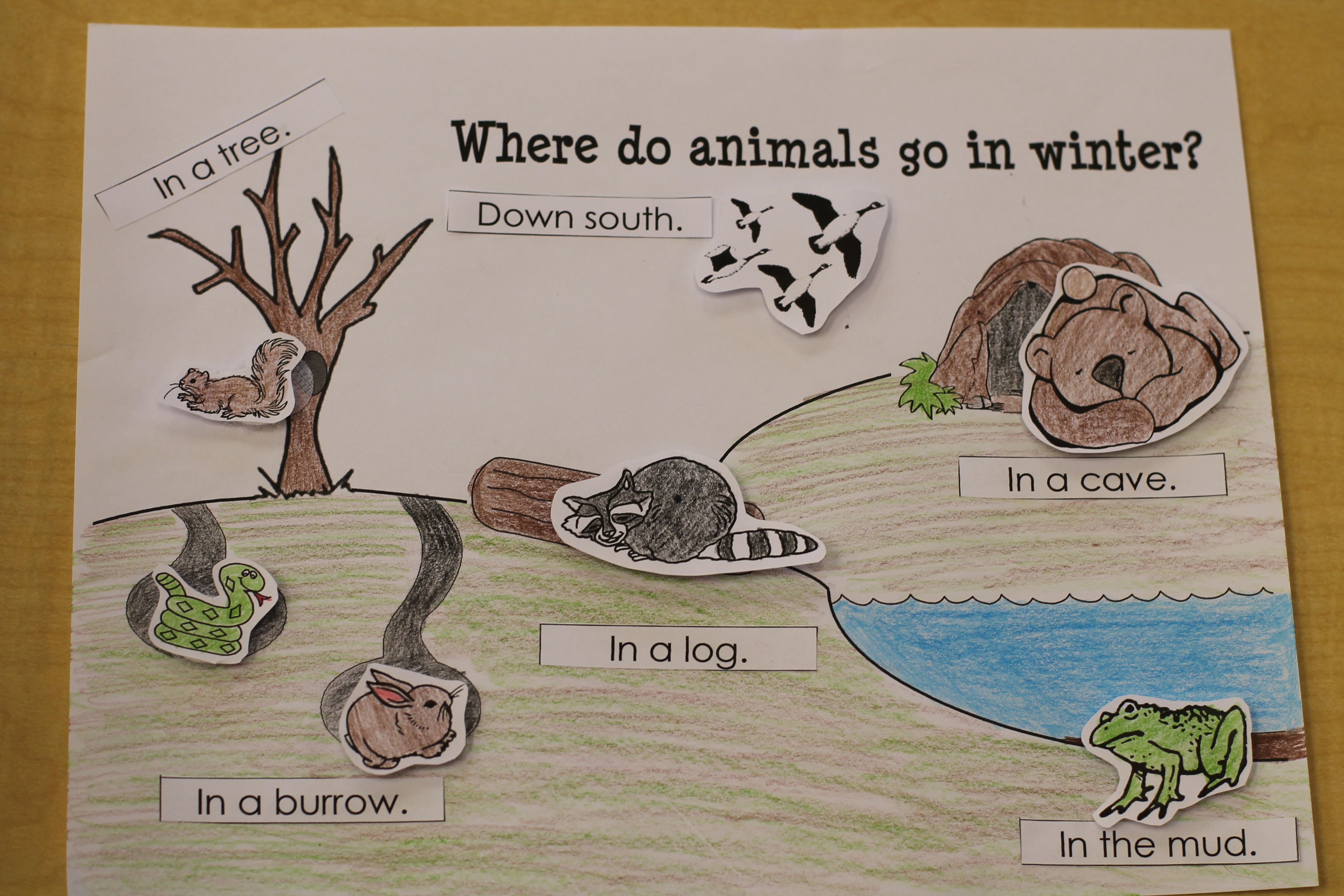

Arctic wildlife have special adaptations that enable them to survive in their icy and changeable environment. Arctic foxes, polar bears, and caribou have hollow hair that traps air, providing them with insulation. Polar bears also have black skin to soak up as much of the sun’s rays as possible. Their fur is almost transparent, but appears white due to the reflection of sunlight. Other animals change color with the seasons to blend in with the changing tundra ground cover, like arctic foxes and ptarmigans that go from brown in summer to white in winter. Some fish that live in or under the ice have antifreeze compounds in their blood, while seals, whales, and walruses have a thick layer of fat, called blubber, that helps insulate them from the cold.

A large portion of the Arctic region includes the Arctic Ocean, which is home to an amazing array of wildlife, including endangered bowhead whales, endangered polar bears, beluga whales, endangered ringed seals, and Pacific walruses.

America’s Arctic includes the 19.6-million-acre Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Located in the northeast corner of Alaska, this protected area is home to more than 200 bird species, which migrate to the refuge to breed in the summer. As many as 300,000 snow geese visit the coastal plain each fall to feed on the tundra. Other wildlife travelers on the Arctic Refuge include the 130,000-member porcupine caribou herd. Each spring, the herd migrates more than 1,400 miles (2,200 kilometers) across Canada and Alaska to calve in the refuge’s coastal plain. It’s estimated that an individual caribou may travel more than 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers) over the course of a single year.

Most of northwestern Alaska consists of the 23-million-acre National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPRA), the largest single tract of public land in the country. The Indiana-sized reserve provides critical habitat for an incredible array of migratory waterfowl that use the four major U.S. flyways to reach all 50 states in addition to many other countries. Canada geese, tundra swans, white-fronted geese, pintail ducks, and brant are among the hundreds of species of migratory birds that nest, feed, and molt in the NPRA each year. The reserve is also home to spectacular terrestrial and marine mammals, including grizzly bears, polar bears, caribou, wolves, and wolverines, as well as beluga whales, bowhead whales, walruses, and several species of seals. The 490,000-animal Western Arctic caribou herd is the state’s largest, and the Teshekpuk Lake caribou herd, numbering about 67,000 animals, is a primary source of subsistence for thousands of Alaska Native residents.

Threats & Conservation

Oil and Gas Development

The Arctic contains abundant oil and gas reserves underneath its icy exterior.

The National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPRA) is managed by the Bureau of Land Management for both the protection of high fish and wildlife values and development of oil and gas. The National Wildlife Federation is working to protect the key habitats that support the remarkable fish and wildlife that flourish in the reserve. Thanks to this work, the Bureau of Land Management finalized a management plan that takes a balanced approach to identify the most important wildlife habitat while providing for oil and gas development where it can be done responsibly.

However, government pressures to open more of the Arctic to oil and gas development threatens the wildlife and people who live there.

The stated mission of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is to «preserve unique wildlife, wilderness and recreational values; to conserve caribou herds, polar bears, grizzly bears, muskox, Dall sheep, wolves, wolverines, snow geese, peregrine falcons, other migratory birds, Dolly Varden, and grayling; to provide opportunities for subsistence uses; and to ensure necessary water quantity and quality.» Only Congress can designate an area as wilderness, so it is up to our elected officials in the Senate and House of Representatives to pass a bill to permanently protect this sensitive landscape for future generations.

Climate Change and the Loss of Sea Ice

Average temperatures in the Arctic are rising almost twice as fast as the rest of the world and are changing the Arctic ecosystem in profound ways—especially the rapid melting of sea ice.

The majority of the Arctic near the North Pole is covered in sea ice. The ice pack is in constant motion, drifting with ocean currents and prevailing winds. Ice is present year-round in the Arctic, expanding during the winter and retreating during the summer. Sea ice is a special feature of the Arctic, and most wildlife there depend on it in some way. Polar bears use the ice as platforms when feeding on seals. Walruses use the ice as a place to rest. There’s even algae that live in the ice.

Arctic sea ice is melting much faster than previously predicted. The region is on track to become an essentially ice-free environment in summer, with a much-reduced ice freeze-up occurring in winter. Already much of the «fast ice,» or ice shelves attached to land, have broken up, including the 300-mile (480-kilometer) Ellesmere Ice Shelf along Ellesmere Island in northern Canada.

There is concern that melting Arctic glaciers and sea ice may raise sea levels around the globe, and that, if enough freshwater is introduced to the North Atlantic, there could be a shift in ocean currents.

Arctic permafrost is also melting, changing tundra to wetlands and shrublands. All of these changes have profound effects on wildlife and the human communities that depend on wildlife for their survival. More oil drilling will only exacerbate the challenges brought on by climate change in this region.

The National Wildlife Federation is working to stop Arctic drilling and combat climate change to stop the loss of tundra and sea ice in the Arctic.

Sources

Arctic Centre, University of Lapland

National Snow and Ice Data Center

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

What’s Trending

Garden for Wildlife Month

Five ways to participate in the 50th anniversary celebration!

Read More

Come Clean for Earth

Take the Clean Earth Challenge and help make the planet a happier, healthier place.

Learn More

Creating Safe Spaces

Promoting more-inclusive outdoor experiences for all

Read More

7 Reasons to Support the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act

A groundbreaking bipartisan bill aims to address the looming wildlife crisis before it’s too late, while creating sorely needed jobs.

Read More

Where We Work

More than one-third of U.S. fish and wildlife species are at risk of extinction in the coming decades. We’re on the ground in seven regions across the country, collaborating with 52 state and territory affiliates to reverse the crisis and ensure wildlife thrive.

Learn More

Damaging the Arctic Web of Life

IMPACTS AT THE ECOSYSTEM LEVEL: DAMAGING THE ARCTIC WEB OF LIFE

Climate change is having profound impacts not only on individual species but also on the ecosystems to which they belong—the interconnected assemblages of species and their physical environment.

VANISHING HABITATS. Climate change is triggering the rapid loss of entire Arctic habitats, most notably sea ice and glaciers, and is leading to the degradation of others. For example, ocean acidification is making Arctic waters unlivable for many calcifying creatures, melting permafrost threatens to drain tundra wetlands, and erosion is degrading coastal habitats.

MOVING EARLIER. As the onset of spring arrives earlier, some Arctic species are advancing the timing of important activities to try to keep pace. The flowering of plants, egg-laying of birds, and emergence of insects have shifted by up to 30 days earlier per decade in some Arctic regions.

MOVING NORTHWARD. Many Arctic species, from shrubs to insects to mammals, are moving northward to keep pace with rising temperatures. [2] However, as species enter new areas, communities are altered and disrupted. For example, the red fox has been moving northward into the tundra, following the expansion of shrubs, which has been linked to declines of the smaller, less dominant tundra-dwelling Arctic fox.

CHANGING SPECIES INTERACTIONS. Climate change is altering relationships among species in the Arctic by changing the availability of food resources and exposing them to new predators, competitors and pathogens as species shift their ranges.

DECLINES AND EXTINCTIONS. Climate change has already been linked to lower survival or population declines of Arctic species from the sea-ice dependent polar bear, to the glacier-affiliated Kittlitz’s murrelet, to the tundra-dwelling caribou, to the marine sea butterfly. Researchers have forecast that at least one species, the polar bear, will be faced with extinction within this century if sea-ice loss is not halted. The loss of species can have far-reaching effects on the functioning of entire ecosystems.

MULTIPLE LAYERS OF IMPACT. Climate change is having multilayered, synergistic impacts on Arctic ecosystems, including threats from increasing human use.

1. Hoye, T.T., E. Post, H. Meltofte, N.M. Schmidt, and M.C. Forchhammer. 2007. Rapid advancement of spring in the High Arctic. Current Biology 17: R449.

2. Post, E., M. C. Forchhammer, M. S. Bret-Harte, T. V. Callaghan, T. R. Christense, B. Elberling, A. D. Fox, O. Gilg, D. S. Hik, T. T. Hoye, R. A. Ims, E. Jeppesen, D. R. Klein, J. Madsen, A. D. McGuire, S. Rysgaard, D. E. Schindler, I. Stirling, M. P. Tamstorf, N. J. C. Tyler, R. van der Wal, J. Welker, P. A. Wookey, N. M. Schmidt, and P. Aastrup. 2009. Ecological dynamics across the Arctic associated with recent climate change. Science 325:1355-1358.

3. ACIA. 2005. Arctic Climate Impact Assessment.

4. Tynan, C. T., and D. P. DeMaster. 1997. Observations and predications of Arctic climate change: potential effects on marine mammals. Arctic 50:308-322.

Arctic ecosystem | PRO-ARCTIC

\\ Home \ Ecology

Conservation of biological diversity in the Arctic. Shell invests in research, development and technology to help reduce the negative impact that an oil and gas company’s operations can have on biodiversity. In addition, the concern is a participant in a number of joint industry projects, for example, to study the acoustic impact on fish, turtles and marine mammals.

Prevent damage

In focusing on biodiversity conservation, oil and gas companies must take into account not only public environmental concerns, but also legal and regulatory requirements, as well as their commercial interests. On the environmental aspects of work in the Arctic, including the problem of possible impact on biological diversity, the concern cooperates with various research and academic institutions, including the University of Alaska.

What makes the Arctic ecosystem unique is ice, which creates permafrost in the ground, and can be either fast ice or floating in the sea. As a result of evolution in the Arctic regions, biological species have emerged that are able to use local conditions. Some of these species are found only in arctic and subarctic regions. These include large marine mammals such as bowhead whales, narwhals and beluga whales, walruses, and some fish species such as capelin and polar cod.

Microscopic plants, the starting point of the Arctic marine food chain, provide food for benthic living organisms (benthos) as well as microscopic fauna, which in turn are food for larger marine animals. A particular abundance of these forms of life is characteristic of the zones, the ice cover of which varies depending on the season: it comes in winter and retreats

in summer.

Some animals, such as polar bears and seals, live mainly on ice or in the sea. Other animals such as caribou (reindeer), musk ox and arctic fox live on land.

For many, the polar bear is a symbol of rich and vulnerable Arctic nature. Any possible impact on the polar bear’s natural habitat could have consequences. With regard to polar bears, Shell complies with regulatory requirements: it provides reports of their presence, trains its employees on how to behave when in close proximity to a polar bear, and how to avoid such an encounter. In cooperation with regulatory authorities and other organizations, the Group may decide that any additional measures are required in the future.

The polar bear is one of the largest predators. To prevent a person from meeting a polar bear, various techniques are used, for example, noise devices such as signal cartridges, firecrackers, horns and sirens to scare away polar bears. Sometimes, due to the appearance of these animals, the company’s specialists had to suspend work. An environmental impact study undertaken in Alaska by the US Mineral Resources Management Service indicated that offshore activities expected to take place in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas would not have a significant adverse impact on polar bears.

Research is currently under way on the polar bear’s response to changes in its habitat due to climate change. The concern is supporting some of this research by providing financial support to the US National Fish and Wildlife Fund and the Polar Bear Conservation Fund.

Shell partners with the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the International Organization for Wetlands in the sustainable management of ecosystems. “Biological diversity is as necessary to man as energy.

In 2008, Shell and Wetlands International initiated a collaborative project to study the impact of the oil and gas industry on Arctic tundra and permafrost, including habitat conservation and restoration in wetlands. This study will help to organize the production of surface and underground works in the conditions of easily vulnerable tundra and permafrost.

The Alaska Experience

Biodiversity is the abundance of forms and species of flora and fauna, from microscopic algae to the tallest trees, from tiny mites to the largest mammals. The well-being of plants and animals depends on the state of their habitat. The Group recognizes that oil and gas production can lead to the disturbance or loss of biological diversity or damage to habitats. Therefore, when evaluating environmental risks, Shell includes in them the impact on biodiversity, which may have a new or ongoing activity of the group. The company carefully monitors the work carried out in areas that international experts have recognized as environmentally vulnerable. Among other things, the group consults with key stakeholders, such as non-governmental organizations, and seeks to: collaborate with other parties to conserve ecosystems; comply with protected area regimes; to form collaborative relationships that enable Shell to contribute to the conservation of the world’s biodiversity.

In 2001, the group implemented its own biodiversity conservation standard, which is the best in the oil and gas industry. This standard is now an integral part of Shell’s health, safety, environmental and social responsibility reporting system. The established mandatory standards set out strict principles and requirements for managing environmental impacts. The corresponding more detailed requirements are specified in the Group Biodiversity Guidelines. For new projects or large-scale expansions of current operations, the company’s specialists conduct environmental impact assessments to identify risks to biodiversity and develop methods to avoid, reduce or control risks. If projects or expansion of activities are carried out in particularly vulnerable areas, the conservation of biodiversity of which is critical, then the group’s environmental impact assessments include action plans for the conservation of biological diversity.

Shell’s research in the seas around Alaska provides valuable scientific information that will remain relevant for future generations. Numerous projects are being implemented in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas, often without analogues, including:

- identification of migratory routes of whales and other mammals;

- walrus tagging with USGS;

- use of unmanned aerial vehicles to monitor marine mammals;

- analysis of the effect of ice masses on the seabed;

- analysis of erosion and alluvium processes in the coastal zone and their impact on the local population;

- water quality control and chemical sampling of sediments;

- identification of the types of living organisms that live on the seafloor and on which many other species depend.

An extensive network of microphones installed on the seafloor records the sounds of whales, seals and walruses, and picks up seismic activity. This helps to understand the distribution, abundance, migration routes of marine mammals, as well as changes in their behavior caused by the activities of oil companies.

Expert observers and specialists collect observational data by tracking mammals from aircraft and small craft. About a third of biologists are representatives of the local indigenous people — Inupiat.

In order to make this work more efficient, the concern is testing unmanned aerial vehicles. Shell helps finance these programs and uses their results for project planning and environmental impact assessment. Research is carried out by independent experts in collaboration with research and academic institutions, including the University of Alaska.

In Alaska, airborne monitors monitor the possible impact of oil company offshore activities on marine mammals such as whales, seals, walruses and polar bears.

Tweet

science is more important than resources — Russia in global politics of Economics at the National Research University Higher School of Economics Valery Kryukov, Doctor of Economics, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Professor at the Faculty of World Economy and World Politics at the National Research University Higher School of Economics, Director of the Institute of Economics and Organization of Industrial Production of the SO and Editor-in-Chief of the ECO magazine.

Most of the Arctic territory and 50% of the region’s GDP belong to Russia. The contribution of the Arctic to Russia’s GDP ranges from 15 to 20%. The development of the knowledge economy makes it necessary to search for new approaches to the development of the region: the old, stereotyped ones no longer work. The role of resources in the Arctic is great, but their importance decreases over time, and knowledge and intelligence come to the fore. As long as the Arctic remains the territory of resource megaprojects implemented by large companies, even their relative success will not lead to the development of the region as a whole.

A new program for the development of the Arctic is on the agenda today. The main priorities are ensuring the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Russia; preservation of the Arctic as a territory of peace, stable and mutually beneficial partnership; ensuring a high quality of life and well-being of the population of the Arctic zone; development of the Arctic zone as a strategic resource base and its rational use in order to accelerate the country’s economic growth; development of the Northern Sea Route as a competitive national transport communication in the world market; environmental protection in the Arctic, protection of the original habitat and traditional way of life of indigenous peoples.

The peculiarities of the Arctic region and its economy include a significant remoteness from sales markets, lengthening of the turnover of financial resources, the absence of local markets, a unique environmental situation, the influence of geopolitical factors and circumstances. As a result, development has a focal character, the level of urbanization is extremely high, unique production and technological complexes and systems are being created that are focused on a high level of decision-making centralization.

There are three main components of the Arctic economy. This is a resource economy associated with the development and use of minerals. At the same time, the non-commodity economy is widely represented in the region — economic activity and the lifestyles associated with it of the small indigenous peoples of the North. Finally, the region is permeated by a public transfer economy — economic activity related to the fulfillment of national obligations and responses to geopolitical challenges.

This combination cannot be sustainable. In large projects for the extraction of hydrocarbons, there is a steady complication of the conditions for development and development, which leads to an increase in all types of risks. Oil and gas fields that were the first to be put into operation (as, for example, in the north of the Tyumen region) are super-large, providing returns on the principles of economies of scale (production at huge capacities with low marginal costs). However, the costs of many of these projects are underestimated.

The costs of extracting resources are taken into account, but they often forget about the costs of transporting them over gigantic distances, and most importantly, that projects are implemented in debt to future generations, who will then face environmental consequences.

The resource base is rapidly changing. There are many resources, but reserves (resources, the extraction of which can be profitable) are getting smaller — the organizational environment does not keep up with the ongoing changes.

The most important task is to ensure the science-intensive nature of activities and increase the role of science-intensive service. What is happening now in the oil and gas north of the Tyumen region? The role of knowledge-intensive service companies, which are based outside the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, is growing. The role of intra-regional services related to drilling and logistics is noticeably decreasing. There is a switch of key functions to those players who are located far outside those areas. This means that it is necessary to build spatial relationships. The Arctic should be connected with centers of competence within the country, especially in its eastern part.

Similarly, the Northern Sea Route does not make sense for Russia without meridional transport routes connecting it with the centers of scientific development and industrial production in Central and Southern Siberia. Otherwise, it will be used only to export natural resources and import equipment for their extraction from abroad without creating any multiplier effect for the country’s economy as a whole.

Unfortunately, there is still no understanding of the project multiplier — how it should be built and how it contributes to the connectedness of the territory. At the moment, this is entirely given over to the corporations implementing the projects, which determine the equipment suppliers. However, this approach leads to paradoxes. So, at the initial stage of the Sabetta project (construction of an LNG plant in Yamal), gravel was supplied from the port of Kirkenes, although Labytnangi is located 150 km away, where the corresponding reserves were specially developed for these purposes in the Soviet years.

On the other hand, it is important to increase the role and importance of local skills — knowledge of specific practices in specific regions. The knowledge economy involves measuring and quantifying the production of knowledge (obtaining patents, other forms of accounting for innovation) and human capital (analysis of the level of education, skills of the workforce). At the moment, almost all registered oil and gas patents are located in megacities (Moscow and St. Petersburg), local knowledge has not yet become the norm in Russia.

In the «Greater», that is, the global Arctic, modern technologies and communication capabilities are emerging and spreading today, which allow us to successfully overcome traditional limitations and challenges and integrate into global chains. A new economic reality is being formed, in which “non-resource” types of economic activity play an increasingly important role, involving the use of creative skills and abilities of the local population.

With new technologies comes new possibilities. The Arctic regions are very attractive for data centers and cloud technology centers. Today one of the Norwegian data centers is located on Svalbard. In addition, electronic services and remote control have every opportunity to improve the safety and comfort of living in remote places, especially in those where the population is decreasing and the proportion of elderly people is growing, and electronic medicine can significantly improve living conditions in these regions.

How can we connect world experience with the realities of Russian life? Three stages are fundamentally important: strengthening the role and place of knowledge-intensive service companies, whose offices are based in key base cities; further, the development of the knowledge-intensive sector can become an impulse for the formation of a broader diversified structure of the economy of resource regions; solving the problems of reconstructing previously created infrastructure and including local contractors and communities of indigenous peoples of the North in the processes of formation and development of the service sector.