Name of figures: General Data Protection Regulation(GDPR) Guidelines BYJU’S

Posted onList of Figures

List of Figures

Campus Community Health • HEERF I, II & III

Figures in your document

- Use Times New Roman for text in the figures. Use size 12 where able, but 10 or 11

size may also be used to fit text within the figure. Line spacing within a figure should

be single-spaced. - All figures should be labeled and formatted in APA style with numbering, title, notes, etc.

- Figures should be placed after the paragraph where they are first mentioned unless

that splits the figure across two pages. Instead of splitting the figure, insert

the figure at the beginning of the next page after it is first mentioned.If your

figure is so large it must be split across multiple pages, type Figure 1 (Continued)

at the top of the next page. - References in your text to figures must reference a specific figure and number: «As

demonstrated in Figure 3…» Do not use, «As demonstrated in the following figure….» - If your figure needs to be rotated because it is too large, rotate just the figure

with the top of the figure at the 1.5″ margin side. - The title of the figure needs to be placed one double space from the figure number.

- It is important to use the same pattern and placement throughout your paper.

If your

figure title is on the top, keep it on the top throughout the paper.

List of Figures page

- Required if there are two or more figures in your document including the appendices.

- Type List of Figures on the top line. Be sure to label this title as a page title

heading to format it properly. See Content/Chapters for more information about headings. - Leave the next line blank.

- Type Page (#), tab once, type Figure 1: Title or caption of figure one.

- If your page number is a single digit, you will need to tab twice so that all figure

names are aligned. - List each figure on a new line.

- If your title/caption is so long it goes onto another line, indent that line to match

where all figure names start. If you have more than one page, do not split title/captions

across pages. - If your list is more than one page, put a page title on only the first page

- Remember all figures in the appendix must be listed on this page.

- Do not use bold or italics.

Figures and Charts – The Writing Center • University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

What this handout is about

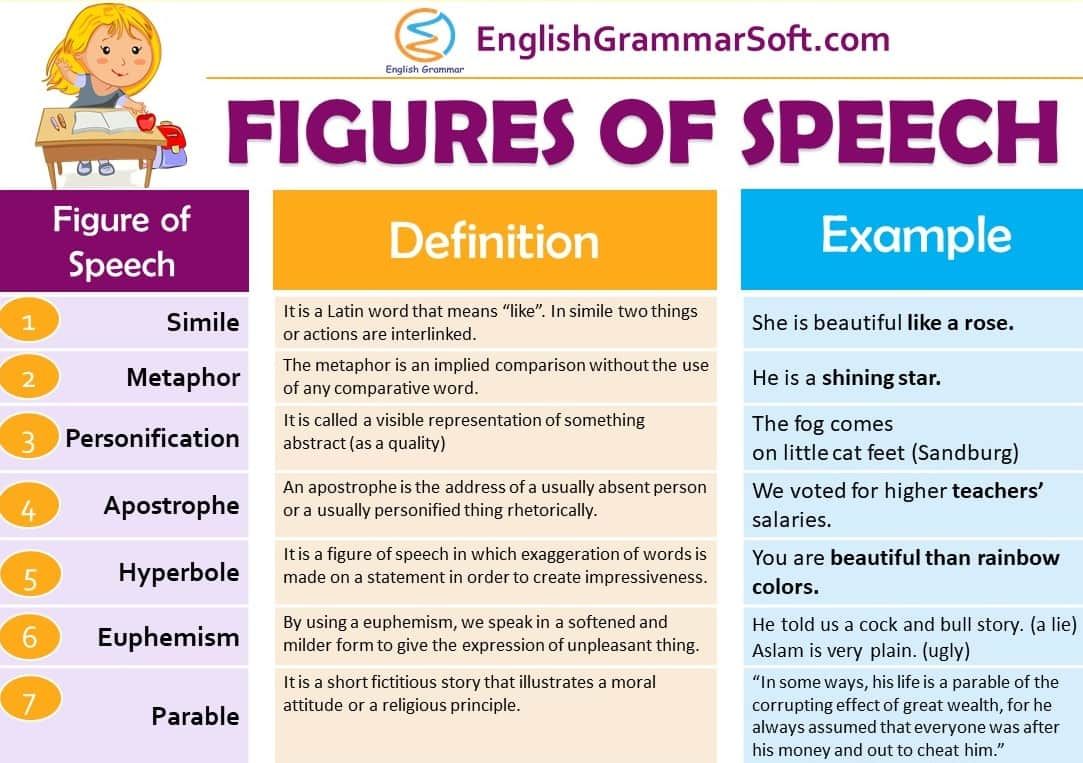

This handout will describe how to use figures and tables to present complicated information in a way that is accessible and understandable to your reader.

Do I need a figure/table?

When planning your writing, it is important to consider the best way to communicate information to your audience, especially if you plan to use data in the form of numbers, words, or images that will help you construct and support your argument. Generally speaking, data summaries may take the form of text, tables or figures. Most writers are familiar with textual data summaries and this is often the best way to communicate simple results. A good rule of thumb is to see if you can present your results clearly in a sentence or two.

So what’s the difference between a table and a figure anyway?

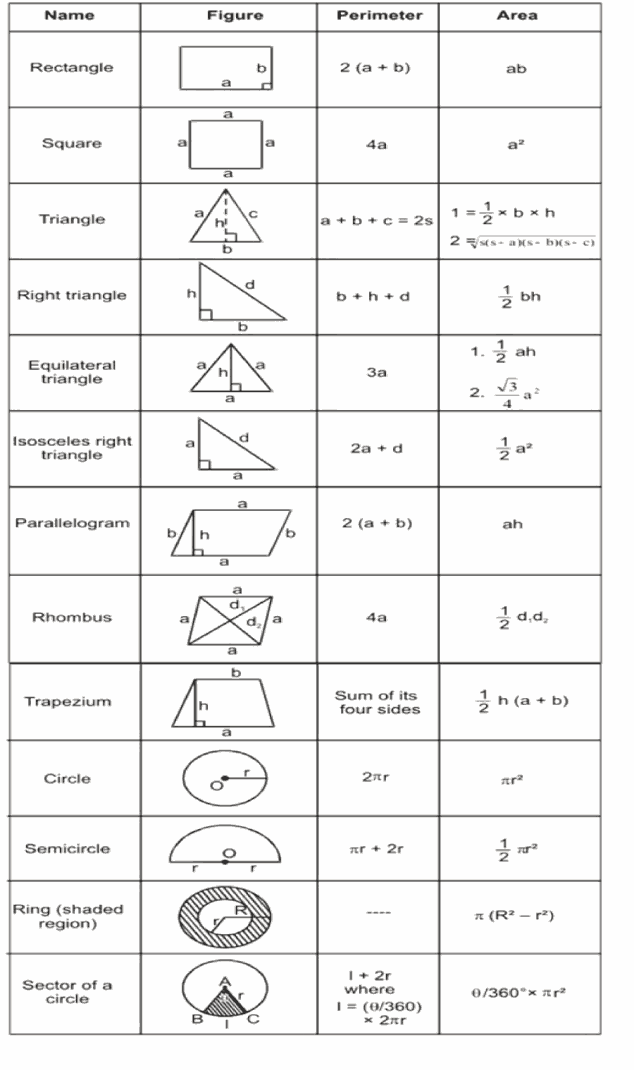

Tables present lists of numbers or text in columns and can be used to synthesize existing literature, to explain variables, or to present the wording of survey questions. They are also used to make a paper or article more readable by removing numeric or listed data from the text. Tables are typically used to present raw data, not when you want to show a relationship between variables.

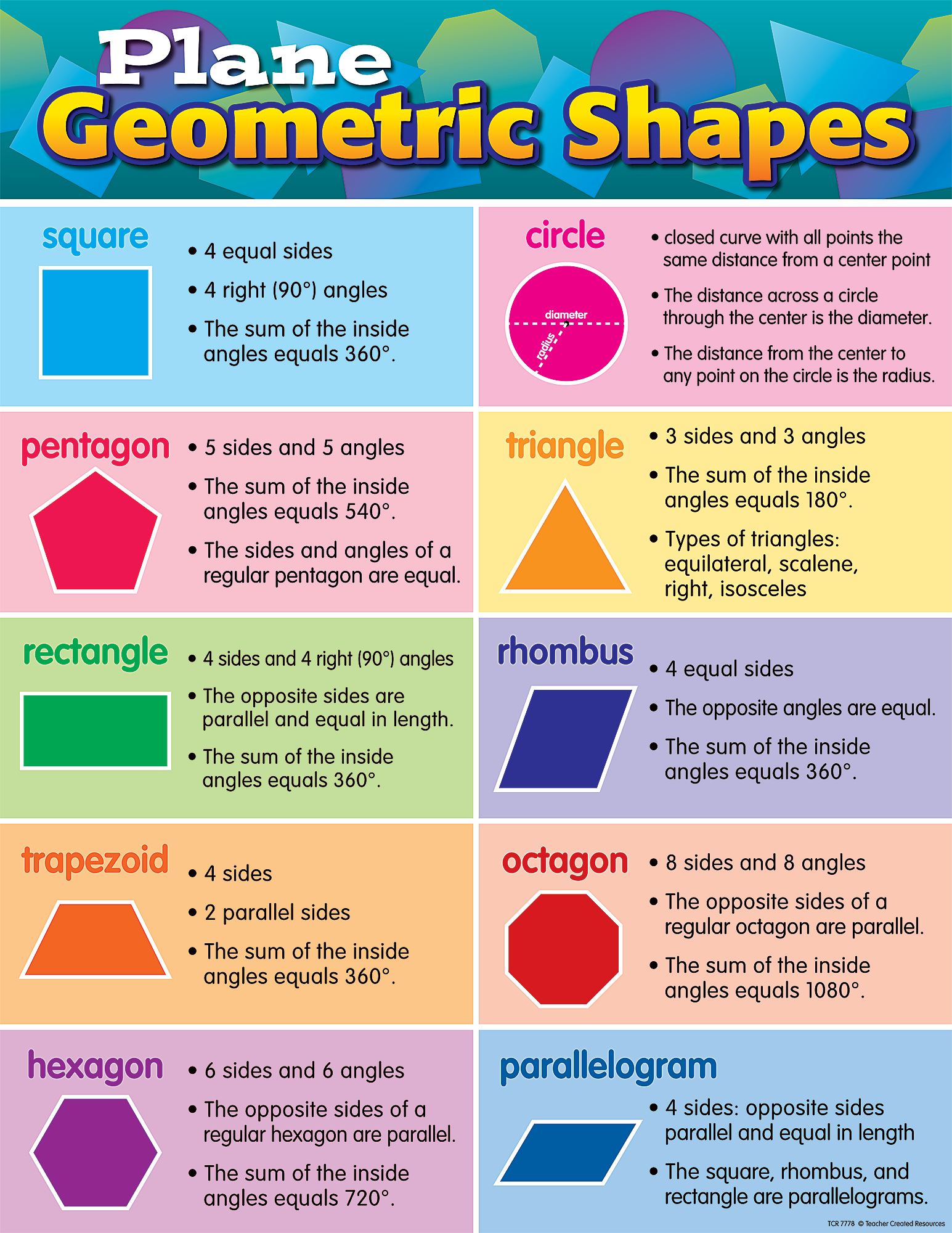

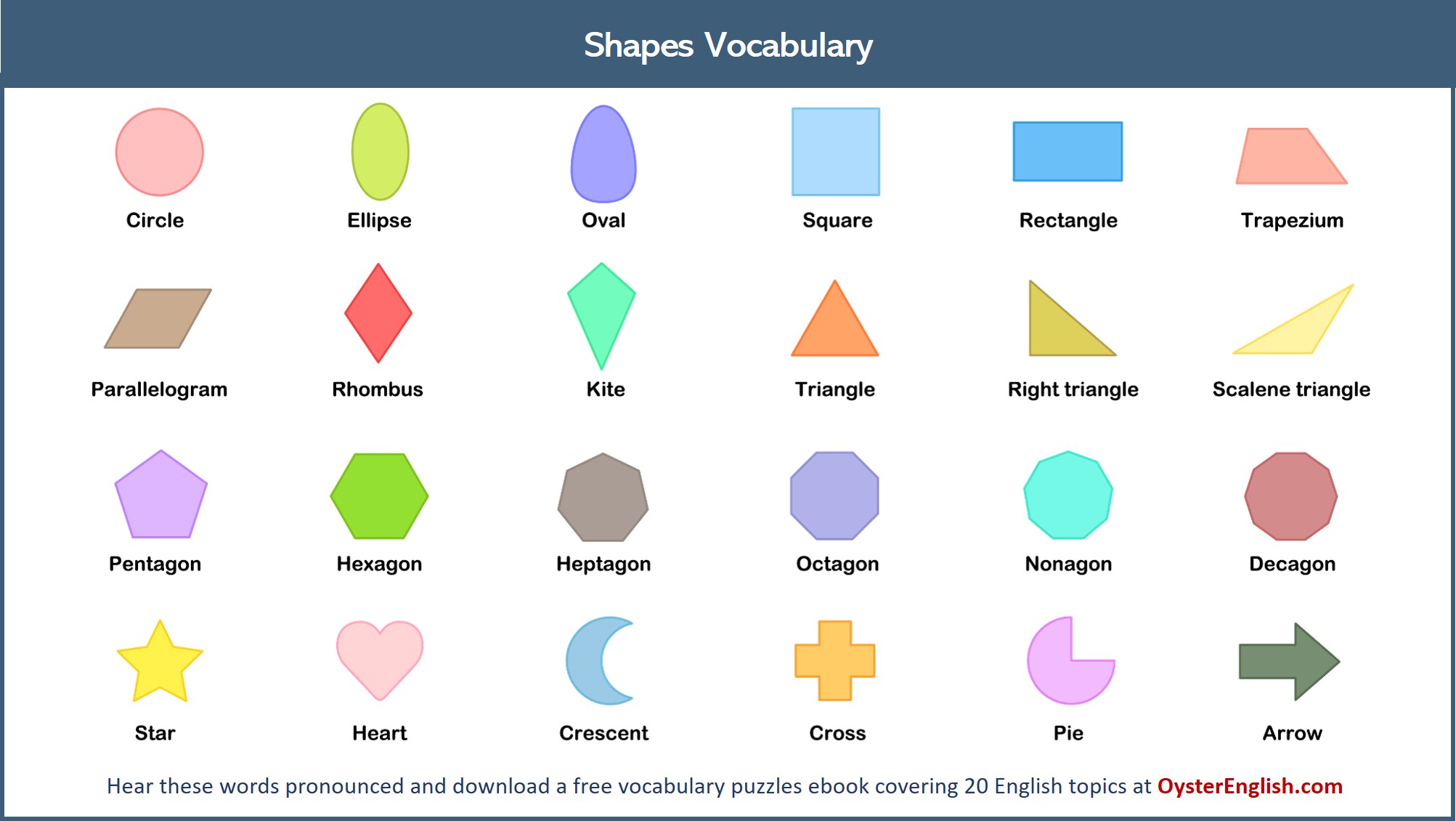

Figures are visual presentations of results. They come in the form of graphs, charts, drawings, photos, or maps. Figures provide visual impact and can effectively communicate your primary finding.

Using tables

Tables are easily constructed using your word processor’s table function or a spread sheet program such as Excel. Elements of a table include the Legend or Title, Column Titles, and the Table Body (quantitative or qualitative data). They may also include subheadings and footnotes. Remember that it is just as important to think about the organization of tables as it is to think about the organization of paragraphs. A well-organized table allows readers to grasp the meaning of the data presented with ease, while a disorganized one will leave the reader confused about the data itself, or the significance of the data.

Title: Tables are headed by a number followed by a clear, descriptive title or caption. Conventions regarding title length and content vary by discipline.

Column titles: The goal of column headings is to simplify and clarify the table, allowing the reader to understand the components of the table quickly. Therefore, column titles should be brief and descriptive and should include units of analysis.

Table body: This is where your data are located, whether they are numerical or textual. Again, organize your table in a way that helps the reader understand the significance of the data.

Other table elements

Tables should be labeled with a number preceding the table title; tables and figures are labeled independently of one another. Tables should also have lines demarcating different parts of the table (title, column headers, data, and footnotes if present). Gridlines or boxes should not be included in printed versions. Tables may or may not include other elements, such as subheadings or footnotes.

Quick reference for tables

Tables should be:

- Centered on the page.

- Numbered in the order they appear in the text.

- Referenced in the order they appear in the text.

- Labeled with the table number and descriptive title above the table.

- Labeled with column and/or row labels that describe the data, including units of measurement.

- Set apart from the text itself; text does not flow around the table.

Table 1. Physical characteristics of the Doctor in the new series of Doctor Who

|

Height |

Age (yrs.) |

|

|

Ninth Doctor |

6’0” |

41 |

|

Tenth Doctor |

6’1” |

35 |

|

Eleventh Doctor |

5’11” |

25 |

Table 2.

|

Personal Appearance |

Wardrobe |

|

|

Ninth Doctor |

Close-cropped hair

Blue eyes Slightly stockier build |

Black leather jacket

Dark colored, v-necked shirts Black combat boots |

|

Tenth Doctor |

Longer, mussed-up hair

Brown eyes Very thin build |

Beige trench coat

Pin-striped suit and tie Chuck Taylors |

|

Eleventh Doctor |

Longer, side-swept hair

Green eyes Slightly stockier build |

Brown tweed jacket

Bow tie and suspenders Black Boots |

Using figures

Figures can take many forms.

Figure captions

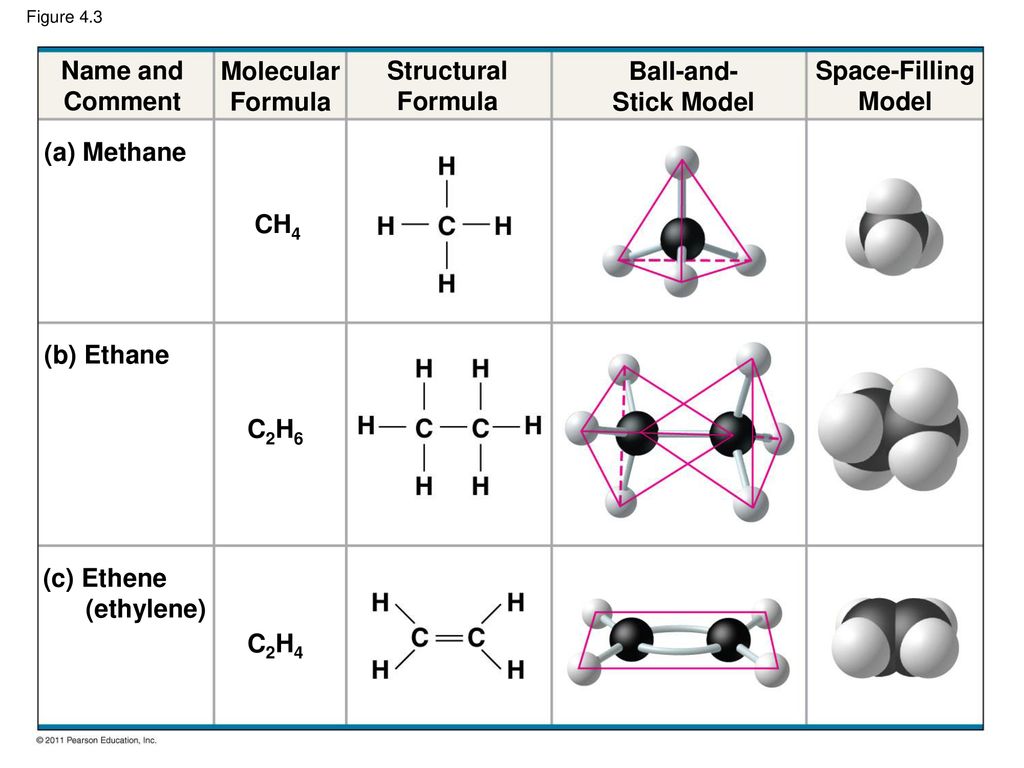

Figures should be labeled with a number followed by a descriptive caption or title. Captions should be concise but comprehensive. They should describe the data shown, draw attention to important features contained within the figure, and may sometimes also include interpretations of the data.

Image

The most important consideration for figures is simplicity. Choose images the viewer can grasp and interpret clearly and quickly. Consider size, resolution, color, and prominence of important features. Figures should be large enough and of sufficient resolution for the viewer to make out details without straining their eyes. Also consider the format your paper will ultimately take. Journals typically publish figures in black and white, so any information coded by color will be lost to the reader. On the other hand, color might be a good choice for papers published to the web or for PowerPoint presentations. In any case, use figure elements like color, line, and pattern for effect, not for flash.

Additional information

Figures should be labeled with a number preceding the table title; tables and figures are numbered independently of one another. Also be sure to include any additional contextual information your viewer needs to understand the figure.

Quick reference for figures

Figures should be:

- Centered on the page.

- Labeled (under the figure) with the figure number and appropriate descriptive title (“Figure” can be spelled out [“Figure 1.”] or abbreviated [“Fig. 1.”] as long as you are consistent).

- Numbered in the order they appear in the text.

- Referenced in the order they appear in the text (i.e. Figure 1 is referenced in the text before Figure 2 and so forth).

- Set apart from the text; text should not flow around figures.

Graphs

Every graph is a figure but not every figure is a graph. Graphs are a particular set of figures that display quantitative relationships between variables.

Pie charts

Pie charts are used to show relative proportions, specifically the relationship of a number of parts to the whole. Use pie charts only when the parts of the pie are mutually exclusive categories and the sum of parts adds up to a meaningful whole (100% of something). Pie charts are good at showing “big picture” relationships (i.

Examples of bad pie charts:

Figure 1. Elements in Martian soil

The chart shows the relative proportion of fifteen elements in Martian soil, listed in order from “most” to “least”: oxygen, silicon, iron, magnesium, calcium, sulfur, aluminum, sodium, potassium, chlorine, helium, nitrogen, phosphorus, beryllium, and other. Oxygen makes up about ⅓ of the composition, while silicon and iron together make up about ¼. The remaining slices make up smaller proportions, but the percentages aren’t listed in the key and are difficult to estimate.

Figure 2. Leisure activities of Venusian teenagers

The chart shows the relative proportion of five leisure activities of Venusian teenagers (tanning, trips to Mars, reading, messing with satellites, and stealing Earth cable). Although each of the five slices are about the same size (roughly 20% of the total), the percentage of Venusian teenagers engaging in each activity varies widely (tanning: 80%, trips to Mars: 40%, reading: 12%, messing with satellites: 30%, stealing Earth cable: 77%). Therefore, there is a mismatch between the labels and the actual proportion represented by each activity (in other words, if reading represents 12% of the total, its slice should take up 12% of the pie chart area), which makes the representation inaccurate. In addition, the labels for the five slices add up to 239% (rather than 100%), which makes it impossible to accurately represent this dataset using a pie chart.

Bar graphs

Bar graphs are also used to display proportions. In particular, they are useful for showing the relationship between independent and dependent variables, where the independent variables are discrete (often nominal) categories. Some examples are occupation, gender, and species. Bar graphs can be vertical or horizontal. In a vertical bar graph the independent variable is shown on the x axis (left to right) and the dependent variable on the y axis (up and down). In a horizontal one, the dependent variable will be shown on the horizontal (x) axis, the independent on the vertical (y) axis. The scale and origin of the graph should be meaningful. If the dependent (numeric) variable has a natural zero point, it is commonly used as a point of origin for the bar chart. However, zero is not always the best choice. You should experiment with both origin and scale to best show the relevant trends in your data without misleading the viewer in terms of the strength or extent of those trends.

Example of a bar graph:

Figure 3. Genders of spaceship crew members in popular television series

The graph shows the number of male and female spaceship crew members for five different popular television series: Star Trek (1965), Battlestar (1978), Star Trek: TNG (1987), Stargate SG-1 (1997), and Firefly (2002). Because the television series are arranged chronologically on the x-axis, the graph can also be used to look for trends in these numbers over time.

Although the number of crew members for each show is similar (ranging from 9 to 11), the proportion of female and male crew members varies. Star Trek has half as many female crew members as male crew members (3 and 6, respectively), Battlestar has fewer than one-fourth as many female crew members as male crew members (2 and 9, respectively), Star Trek: TNG has four female crew members and six male crew members, Stargate SG-1 has less than one-half as many female crew members as male crew members (3 and 7, respectively), and Firefly has four female and five male crew members.

Frequency histograms/distributions

Frequency histograms are a special type of bar graph that show the relationship between independent and dependent variables, where the independent variable is continuous, rather than discrete. This means that each bar represents a range of values, rather than a single observation. The dependent variables in a histogram are always numeric, but may be absolute (counts) or relative (percentages). Frequency histograms are good for describing populations—examples include the distribution of exam scores for students in a class or the age distribution of the people living in Chapel Hill. You can experiment with bar ranges (also known as “bins”) to achieve the best level of detail, but each range or bin should be of uniform width and clearly labeled.

XY scatter plots

Scatter plots are another way to illustrate the relationship between two variables. In this case, data are displayed as points in an x,y coordinate system, where each point represents one observation along two axes of variation.

Example of a scatter plot:

Figure 4. The effect of weather on UFO sightings

The scatter plot shows the relationship between temperature (x-axis, independent variable) and the number of UFO sightings (y-axis, dependent variable) for 53 separate data points.

XY line graphs

Line graphs are similar to scatter plots in that they display data along two axes of variation. Line graphs, however, plot a series of related values that depict a change in one variable as a function of another, for example, world population (dependent) over time (independent). Individual data points are joined by a line, drawing the viewer’s attention to local change between adjacent points, as well as to larger trends in the data. Line graphs are similar to bar graphs, but are better at showing the rate of change between two points.

Example of an XY line graph:

Figure 5. Age of the actor of each Doctor Who regeneration (1-11)

The line graph shows the age (in years) of the actor of each Doctor Who regeneration for the first through the eleventh regeneration. The ages range from a maximum of about 55 in the first regeneration to a minimum of about 25 in the eleventh regeneration. There is a downward trend in the age of the actors over the course of the eleven regenerations.

General tips for graphs

Strive for simplicity. Your data will be complex. Don’t be tempted to convey the complexity of your data in graphical form. Your job (and the job of your graph) is to communicate the most important thing about the data. Think of graphs like you think of paragraphs—if you have several important things to say about your data, make several graphs, each of which highlights one important point you want to make.

Strive for clarity. Make sure that your data are portrayed in a way that is visually clear. Make sure that you have explained the elements of the graph clearly. Consider your audience. Will your reader be familiar with the type of figure you are using (such as a boxplot)? If not, or if you’re not sure, you may need to explain boxplot conventions in the text. Avoid “chartjunk.” Superfluous elements just make graphs visually confusing. Your reader does not want to spend 15 minutes figuring out the point of your graph.

Strive for accuracy. Carefully check your graph for errors. Even a simple graphical error can change the meaning and interpretation of the data. Use graphs responsibly. Don’t manipulate the data so that it looks like it’s saying something it’s not—savvy viewers will see through this ruse, and you will come off as incompetent at best and dishonest at worst.

How should tables and figures interact with text?

Placement of figures and tables within the text is discipline-specific.

You can use text to guide the reader in interpreting the information included in a figure, table, or graph—tell the reader what the figure or table conveys and why it was important to include it.

When referring to tables and graphs from within the text, you can use:

- Clauses beginning with “as”: “As shown in Table 1, …”

- Passive voice: “Results are shown in Table 1.”

- Active voice (if appropriate for your discipline): “Table 1 shows that …”

- Parentheses: “Each sample tested positive for three nutrients (Table 1).

”

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial. We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

American Psychological Association. 2010. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association. 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bates College. 2012. “Almost everything you wanted to know about making tables and figures.” How to Write a Paper in Scientific Journal Style and Format, January 11, 2012. http://abacus.bates.edu/~ganderso/biology/resources/writing/HTWtablefigs.html.

Cleveland, William S.

Council of Science Editors. 2014. Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers, 8th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

University of Chicago Press. 2017. The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

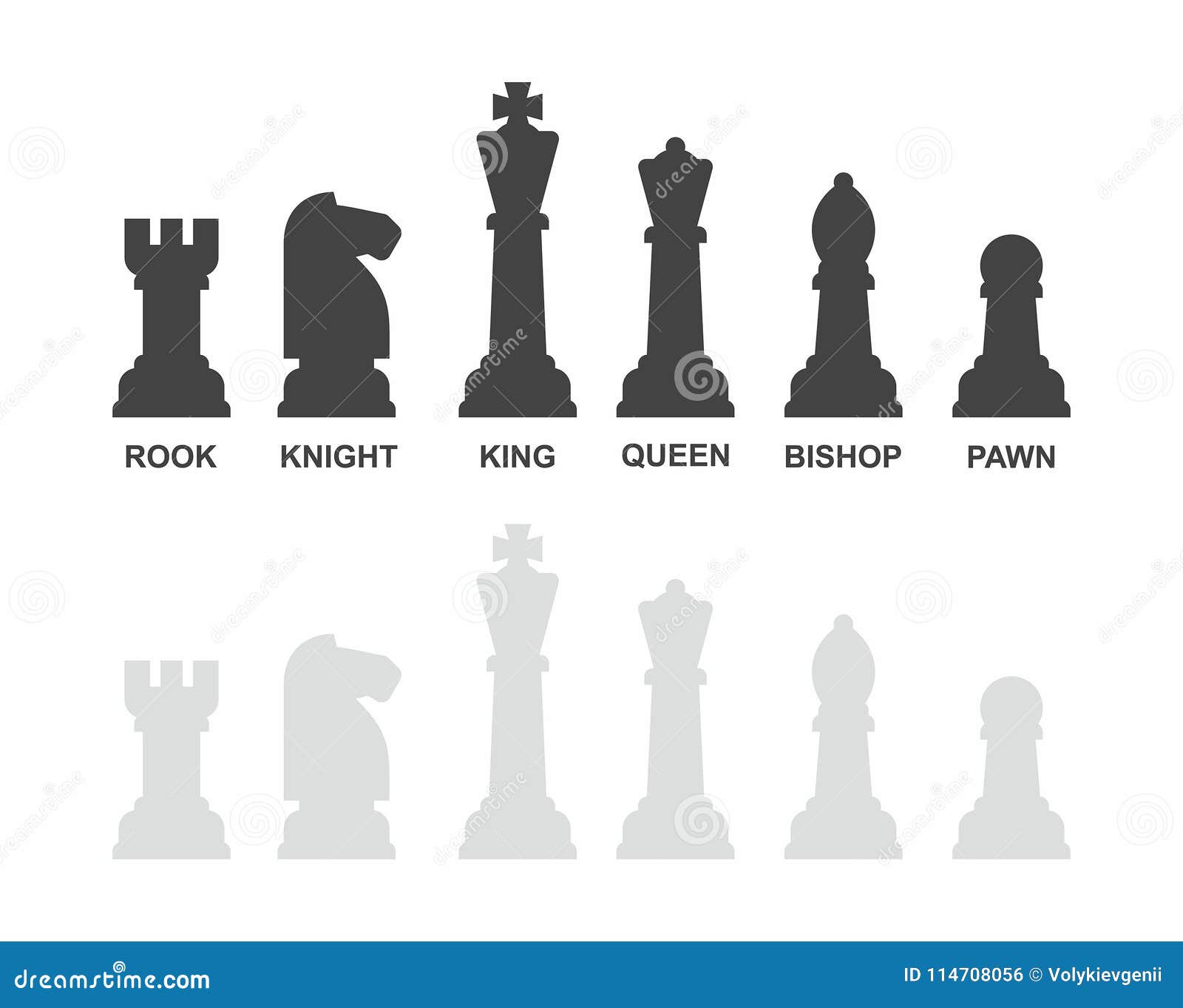

Chess and chess pieces (names, execution, history) / Sudo Null IT News

Once in India there was a very wise ruler. During his reign, the country prospered and he had two twin sons who differed from each other only in that they liked to wear different clothes. One liked to walk in white clothes, and the other in black.

Not the myth you expected, right? But there are many myths. An incomplete list of how chess «appeared» can be found here . I won’t list them all in the article — it’s too big. But besides legends, chess has other interesting historical features. That’s what I want to talk about. Just cramming how the pieces move is not so interesting. And to tell children fairy tales or just about the names of figures — for this, one lesson is usually not enough.

The idea to write this article, stepping back from the course of chess, was born on the basis of comments and a dispute — is a pawn a piece or not. An unequivocal answer was given in the comments from my point of view, but all the same, controversial names like «queen», «officer», «tour» and others remain outside the brackets. That’s what I want to write in more detail in this article.

Before starting the excursion into history, let me remind you about the course articles published on Habré:

-

A dozen tips on how to teach a child chess.

And not only (introduction)

-

Studying the rook (part 1)

-

Studying the bishop (part 2)

-

Studying the queen (part 3)

900 16

-

Learning about the horse (part 4)

-

Learning the pawn (part 5)

History

It is believed that chess is a game that developed from the game of Chaturanga. I think everyone knows about the classic legend when the sage asked for the invention of chess to fill the chessboard with grains of wheat, so that on each next cell there were 2 times more grains than on the previous one (if suddenly someone does not know it, then it is on the link to the list myths which is given at the very beginning of the article). In this case, the mass of all grains of wheat would be equal to 1 199 038 364 791 120 kg. By the way, children perceive such figures poorly, because they need to be compared with something, and there is still little experience. Therefore, it is better to explain the mass by comparison, for example by comparing it with the annual harvest on the entire planet.

The first evidence of the game «Chess» is around 600 AD. It was at this time that the figures imitating reality took shape. The very mention is found in the legend of the 6th century in the Persian poem Shahnameh (Book of Kings). The legend was about how an Indian raja, who paid tribute to the powerful Persian Shah Khosrov, sent a messenger to him with a message written on silk and precious gifts. Among them was a magnificent board for the game and figures. The message was a challenge to the Shah’s courtiers: they had to explain the meaning of this Indian game. If successful, the Raja promised to increase the amount of tribute; if the wise men could not solve the riddle, then it was proposed to pay tribute to the shah. The challenge was accepted. The shah’s wisest vizier, Buzurgmihr, thought day and night, then announced the decision: «The board is a battlefield, on one side is the shah with his army, his vizier is next to him, soldiers line up in front, ready to attack, then war horses, on either side of them — chariots.

The earliest figures found in 1977 during excavations in Afrasiab (Samarkand) date back to the 7th century AD. 7 figures carved from ivory were found — an image of a vizier, a chariot, an elephant, two armed horsemen and a foot soldier.

Figures found in 1977 during excavations in Afrasiab (Samarkand)

When the Arabs captured Iran in the 7th century, they adopted many of the laws and customs of the more civilized people subordinate to them. Including shatranj (as chess is called in Arabic). The game quickly spread throughout the Arab world and by 950 firmly rooted in the Arab territories.

In the 10th century, Arab chess reached Spain, where it spread thanks to the Moors. By the 12th century, chess had become a favorite pastime in feudal Europe. The pieces retained the Arabic names: king — check, queen — firzan, bishop — fil, horse — faras, rook — roc and pawn — canoe.

Although there are no specific prohibitions in the Qur’an regarding carved chess pieces, these prohibitions existed within Islamic culture. Therefore, under these conditions, «pictorial» chess could not be preserved, and simple geometric figures replaced three-dimensional carvings.

On the left is a Lebanese glass figure, possibly a king or queen, on the right is a figure of a king or queen of the 14th century found in England

In Christian Europe, the situation was different: the work of stone carvers was in demand in Gothic and Baroque architecture, where carved sculptural decoration was widely used. And during the Early Middle Ages, the masters who made chess pieces had to give them new names that would be easy to remember. Arabic names did not make sense for the inhabitants of Christian Europe. We will return to these names later when we consider each figure separately.

Carvings of the 12th century found on the island of Lewis (Norway)

It is also worth noting that already in the early European «pictorial» chess, the image of the queen replaces the Arab vizier.

At the end of the 15th century, chess players in Spain and Italy began to experiment with rules of chess that had hardly changed since they appeared in Europe in the 10th century. According to the new rules, a pawn, making its first move, could move two squares at once. The elephant acquired such freedom of movement that it could walk along the entire length of its diagonal. The queen, who until then could only move one square diagonally, gained the right to move around the entire perimeter of the board.

The Spaniards and the French called the new game «Queen’s Chess». The Italians were less courteous and called it «the game of the mad queen.» The new chess rules demanded more ingenuity from the players.

In Europe in the XIV-XV centuries, lathes became widespread, which could not but affect chess as well — their usual appearance underwent changes. Carved chess gave way to chess made on a lathe.

Florentine chess set by Fabiano Embriaci around 1450 English chess around the 14th-15th centuries

Not only chess itself has changed, but also chess terminology.

|

♔ ♚ |

♕ ♛ |

♗ ♝ 9 0073 |

♘ ♞ |

♖ ♜ |

♙ ♟ |

|||||||

| 9000 2 Indian |

shah |

wazir |

fil |

asp |

rukh 8 |

Arabic |

shah |

firzan |

fil |

faras |

rkhkh |

baidaq |

|

Spanish |

rey |

re ina |

alfil |

caballo |

torre |

peon |

||||||

| 900 02 Italian |

re |

regina |

alfiere |

cavaliere 90 073 |

torre |

pedina |

||||||

|

French 73 |

fou |

cavalier |

tour |

pion German |

konig |

konigin |

laufer |

springer |

turm |

bauer |

||

|

Dutch |

koning |

koningen |

raadsheer |

ridder |

kasteel |

pion 0002 English |

king |

queen 6 rook |

pawn |

|||

|

Russian 3 |

bishop |

knight |

rook |

pawn |

||||||||

|

Serbian |

edge |

edge |

lovac |

jumper 90 073 |

top |

pawn |

We will return to this plate later.

In fact, in a very, very concise way, I retold the key points from Gareth Williams’ book «Chess. History. Pieces. Players», 2004, ART-RODNIK publishing house. The entire text that is written above in the book takes about 55 pages with 1-2 illustrations on each sheet. I recommend reading this book if you are interested.

Modern chess sets

Currently, the Staunton chess set is considered the standard of chess pieces. Howard Staunton (1810-1874) was a renowned Shakespeare scholar and chess champion. Staunton chess got its name in honor of this outstanding person. They were made according to sketches by Nathaniel Cook, who registered them with a special act on March 1, 1849. At his request, Staunton entered his name on the document.

Staunton chess pieces

In 1924, the World Chess Federation, choosing pieces for international tournaments, opted for Staunton chess, providing them with a special stigma.

But let’s get back to the chess sets. Currently, there are many sets of chess pieces. I tell the children about this in the 2nd lesson, when I show them all. I have a couple of souvenir chess sets that the kids really like. All modern sets have the following trends:

-

The pawn is always the smallest piece

-

The king is always the largest piece

-

The knight in all sets looks like a knight, or its silhouette is visible

- 900 02 Rook usually looks like a tower.

When I explain to children how to determine which piece is which, I recommend doing the following

-

Find 8 pawns.

-

Find the king (he is the tallest, but I saw the option that the fattest for example)

-

Find a queen (this is a piece that has no pair)

-

Find a rook (usually a turret)

-

Find a knight

- 9000 2 The remaining piece is the bishop.

This is the simplest algorithm for finding shapes in any set. In advance of objections, I will say that the bishop is often more difficult to identify than other pieces. It seems that this figure is simply recouped. I have a set in which elephants are camels … And how to determine that a camel is an elephant? Only as I described above — by elimination.

And now about the names of the figures in more detail.

King

In almost all languages, a king is either a king or a shah, and in Bulgarian a king. It so happened historically that it was he who was the supreme power in the country. Therefore, the options are quite limited — king / shah / padishah / king. So the name of this particular figure is almost unchanged, which cannot be said about the rest.

Queen

Queen fully reflects history and culture. And this is one of the pieces that, after getting to Europe, returned back to Asia with a different move. But the name in Asia did not change.

It is very interesting to learn history through chess. For example, I always cite children’s fairy tales and ask the children a question — who is the leader in the country in fairy tales (you can consider other fairy tales — it will be similar there) Snow White and Aladdin. The correct answer is king/queen in the first and check/vizier in the second.

Perhaps the only exception to this is the name Queen in Estonia. I don’t know why, but there the Queen is called lipp, which means Flag in translation. The fact that the Flag Bearer is next to the King during the battle is normal, but nevertheless the name is strongly knocked out of the generally accepted canon. Perhaps someone knows the reason, I could not find it.

Therefore, the correct name for a queen in Europe is Queen . And in Russia — Queen . In this regard, it was interesting to observe how they got out in the translation of the series « Queen’s Gambit «, half losing its meaning … In the original, the title itself indicates the sacrifice of a woman because of her favorite hobby and means that it is also the name of a chess opening, but the name » Queen’s Move «loses its charm without explaining what it is and completely flips the title of the series into a different rut.

Rook

My favorite topic in chess pieces is the Rook. Here history made the squiggle even cooler than with the Queen.

Let me remind you — initially the Rukhh bird stood in the place of the boat. Visually, this figure was similar to Rook. Further, it is worth considering the historical expansion of chess together with wars, because chess is a military operation on a chessboard. So, in Rus’, Ladya is one of the key military units for quickly moving from one place to another (according to Boris Akunin, the word Russ comes from the word water (rose) due to the presence of many waterways). Additionally, the figurine of the Rukhh bird looked like a boat. And here we do not forget that each nationality stylized chess pieces for themselves, which in Rus’ led to the fact that Rukhh became a Rook.

And what about in Europe? If you remember historically, then in the Arab world, chess pieces gradually switched to geometric primitives (there was no such thing in Rus’). Together with the name Rukhkh, when processing and making «Fine» chess, it is not surprising that some of the authors took the path of depicting a tower (torre in Spain and Italy). If you look at Europe, it is noticeable that the style of the figure is mainly traced in this name. Even the name of the tour that some people use is mobile siege tower . But in England, the name of the boat is different — rook, which, when pronounced, is similar to the name of the Rukh bird.

Another point is connected with a move called castling — castling (in English), which literally means — to hide the king in the castle behind the tower. And the tower (in some translations, the castle) in this case is just Rook.

Therefore, I always emphasize to children that in Russia, Ladya is exactly BOAT .

Elephant

Another interesting figure. To be honest, I did not expect that upon closer examination, you can tell more about him than about the rook. But it turned out that it was.

Initially, the Elephant was just an elephant — a combat unit that fought on the battlefield and was quite strong. As already written earlier, in the 15th century, the elephant figure acquired the ability to walk along the entire diagonal. But even more interesting was the transformation of its name.

In Rus’, the elephant, as it was an elephant (exotic animal), so it remained an elephant. True, for some time the figure was called an officer, but then the old name was returned — an elephant.

In Europe, the name of the elephant was transformed differently. The names of the figures in Europe were redefined in the religious XV century, and here it is quite clear that after the king and queen, the clergy are next, they also stand next to the royal couple.

Upd . Here I dare to make a correction. A dictionary search yielded a translation that, in my understanding, is closer to the elephant story. And it is this word that is consonant with the Arabic al fil

In Italy, the name of the elephant is translated as standard-bearer , which is also determined by its approach to the king on the battlefield.

Interestingly, in France, the elephant has the name (le) fou which translates as jester or crazy.

In other languages, the elephant is called catcher (Serbo-Harvatian), archer (Slovak), officer (Bulgarian). I think that the name is determined precisely by approaching the king and queen (precisely to them, because this name of the elephant is found only in European countries).

And only in Estonia the elephant is called oda , which means « spear «. Well, somewhere the elephant should have a name in its course.

Here is such an interesting elephant 🙂 And he is not an officer in Russia at all.

Horse

Everything is easier with a horse. The horse is the animal that allowed humanity to spread throughout the world, gave freedom of movement and power. Horses are loved by both adults and children. In fact, the horse is present in the mythology, I think, of all countries where this domesticated animal is found.

Knights on horseback gave a prototype to a chess piece. In English, the figure is called — Knight — Knight. And other languages \u200b\u200bdo not lag behind him — a jumper, a kovalier, a springer (jumper).

Pawn

That piece, because of which the whole dispute began in the last article. Yes — a pawn is a piece, although sometimes it is not used in this sense and in some cases it is not considered. In fact, if we consider the modern world, then someone who is especially offended can exclaim «What! Calling a pawn NOT a piece is NOT tolerant! This is discrimination!» And it’s true. The pawn is a full-fledged chess piece, with its own rules and features. It is the smallest and cheapest by the standards of chess. But if there are no pawns, then the game can be lost.

Again, if you look at chess historically, the initial formation of pawns forms a phalanx — a formation used in combat.

True, there were some funny names here too. I do not know how true this is, but nevertheless in the text of this article the following words were encountered (I quote the text in full) — «the inhabitants of the Faroe Islands went the farthest, deciding that little women must certainly be at the forefront of the chess army.». And what? Fine! And now try to say that a woman is not a figure.

Conclusion

I must say right away — it is possible that some of the information from what I wrote has objections, but I am not a historian. I did the analysis based on the information that was found on the Internet, plus a consideration of the historical development of chess in Europe.

Initially, the article was conceived as an explanation of why the pawn is a piece and why the Queen is not the Queen everywhere. But I had to go further and deal not only with the Rook, but also with the Bishop. Honestly, it was interesting to delve into the heap of information that is. It is a pity that most Internet writers consider this issue very narrowly and do not go further in their reasoning about the names of figures. Most often this applies to Rook and Bishop.

In fact, in the classroom I try to give children this information in a more interesting way than I have described here, after all, children perceive information differently. My goal is to get children interested in chess.

Let me remind you that you can sign up for classes on the website. All the terms and conditions of the classes are written on the site. If you have questions — ask — I will answer.

Area

The Area command is used to determine the area of an arbitrary figure.

| How to call a command |

Procedure

1. Pick a point inside the enclosed area. The figure, the area of which will be measured, will be highlighted in color. The name of the resulting figure will appear in the Objects field of the Options Bar. The indication of the figures is described in detail below.

2. Set the measurement parameters. Read more…

|

Only those objects that are located in the current view can be used to calculate the area (for information about changing the state of views, see Changing the state of a view). |

You can quickly view the measurement results, or you can enter them in the Information window.

When quickly viewing measurement results, the value of the area of the specified figure is displayed next to the cursor. You can view the area values of other shapes by hovering over them. To enter measurement results into the Information Window, successively click inside these shapes with the mouse.

You can save or print the measurement results. To do this, use the menu commands of the Information window.

3. To end the command, click the Finish button on the Options Bar or close the Information Window.

|

To measure the area and calculate the coordinates of the geometric center of a complex figure, consisting of several parts and / or with holes, use the command of the MDC of planar figures. |

Pick shapes

To measure the area of a closed area, pick a point inside it.

Similarly, you can specify several enclosed areas. The names of the resulting shapes will appear in the Objects field. The Information window will display a list of measured areas. At the end of the list is the sum of all measured values.

To exclude a shape from the list, specify it again or delete the name of the shape from the Objects field. In this case, the list in the field will be renumbered, and the selection of this figure will be canceled. The entry about the area of the figure will be removed from the Info Window, and the sum of the areas will be recalculated.

Using the Options Bar, you can calculate the area of the following figures.

•A figure formed by a set of geometric objects. To do this, click the Collect Path button on the Options Bar, and then specify the path segments.

If your

If your

”

” And not only (introduction)

And not only (introduction)