Good verbs: THE List of Strong Verbs to Make Your Content Pop, Fizz & Sparkle

Posted onTHE List of Strong Verbs to Make Your Content Pop, Fizz & Sparkle

Strong verbs add action, vitality, color, and zest to your writing. But what are strong verbs? And how do you use them?

Do you ever read text and wonder …

Why do the words jump off this page?

Why does this writing feel energetic and strong?

Why is it so fast-paced?

And do you wonder why your draft text seems a tad limp in comparison?

It happens to all of us.

First drafts often require an injection of power and pizzazz. First drafts are full of weak verbs, and weak verbs make your writing limp, flabby, and listless.

In contrast, strong verbs add action, vitality, color, and zest. So, the “secret” to writing with gusto is to choose stronger verbs.

Want to write with more power?

Click here to get the 22-page ebook How to Choose Words With Power and Pizzazz (it’s free!)

What are strong verbs?

Strong verbs engage your senses, and help readers picture a scene (verbs in bold):

You feel the air reverberating when he slams his fist on the table. The teacups jiggle, his face reddens, and his voice thunders.

Strong verbs allow readers to visualize actions. Instead of only reading words, they’re drawn into your writing, experiencing your story.

But strong verbs don’t need to convey powerful action. Subtle action can evoke powerful feelings, too. For instance:

He cradles the baby, strokes her dark hair, tickles her chin, and hums a lullaby.

Strong verbs are precise and concrete. In contrast, weak verbs are abstract and generic—they don’t help you visualize a scene. Examples of weak verbs are “to be,” “to provide,” “to add,” and “to utilize.” You can’t picture these words.

For instance, if someone provides feedback, is he shouting his comments? Or lecturing you with a smug face? Or perhaps scribbling a few suggestions in the margin of your handout?

You can’t picture “provide feedback,” but you can visualize “shouting,” “lecturing,” and “scribbling.

Examples: How strong verbs breathe life into abstract ideas

Over the weekend, I read Ray Bradbury’s “Zen in the Art of Writing.” I enjoyed his word choice, and I loved how his verbs breathe life into abstract concepts, like storytelling and the Muse.

For instance, he describes how he started writing stories based on lists of nouns:

And the stories began to burst, to explode from those memories, hidden in the nouns, lost in the lists.

And he writes about the Muse:

The Muse, then, is the most terrified of all the virgins. She starts if she hears a sound, pales if you ask her questions, spins and vanishes if you disturb her dress.

And on eating books:

I tore out the pages, ate them with salt, doused them with relish, gnawed on the bindings, turned the chapters with my tongue!

Bradbury’s choice of strong verbs (like “gnaw” and “douse”) adds zest and power.

Strong verbs in business writing

You might think strong verbs are only for fiction writers.

But that’s untrue.

Here’s Nancy Duarte in her book “Resonate” (about engaging your audience with story-based presentations):

Throughout history, presenter-to-audience exchanges have rallied revolutions, spread innovation, and spawned movements.

And:

When a great story is told, we lean forward, and our hearts race as the story unfolds.

And:

Haven’t you often wished you could make customers, employees, investors, or students snap, crackle, pop, and move to the new place they need to be in order to create a new future?

Here’s an example of Apple’s copy:

So whether you’re listening to music, watching videos, or making speakerphone calls, iPhone 7 lets you crank it up. Way, way up.

And:

Apple Watch Series 2 counts more than just steps. It tracks all the ways you move throughout the day, whether you’re walking between meetings, doing cartwheels with your kids, or hitting the gym.

“To do” in the last sentence is, of course, a weak verb. Apple’s copywriters could have changed “doing cartwheels with your kids” into “cartwheeling with your kids” without disrupting the rhythm and making the sentence stronger.

It is nouns and verbs, not their assistants, that give good writing its toughness and color.

~ Strunk and White (in the Elements of Style)

How to choose strong verbs

No clear distinction exists between strong and weak verbs. It’s a gliding scale, and it’s up to you as a writer to decide how strong you’d like your verbs to be.

For instance, “to walk” is stronger than “to go” because it gives you an indication of how someone moved.

- to saunter: picture a girl walking rather leisurely, perhaps peeking into the shop windows

- to hike: picture a woman in walking boots with a backpack, walking at a good pace

- to shuffle: picture an elderly woman moving ahead gingerly, hardly lifting her feet

- to trudge: picture a girl in wellies making a big effort, perhaps walking through the snow or mud

- to stride: picture a lady walking as if on the catwalk, with long strides

- to plod: picture a tired woman with sagging shoulders, walking rather tiredly

Strong verbs can also be used for abstract language. For instance, you could say you generated ideas during your brainstorm session. But how did your ideas arrive? For instance:

- A few ideas popped into your mind

- Your mind exploded with ideas

- A stream of ideas burst forward

- Ideas first trickled, then gushed forth

- The brainstorm session spawned a stream of ideas

Strong verbs are more precise than weak verbs; they can paint clear pictures—even of abstract activities like thinking and generating ideas.

How to improve your sentences with strong verbs

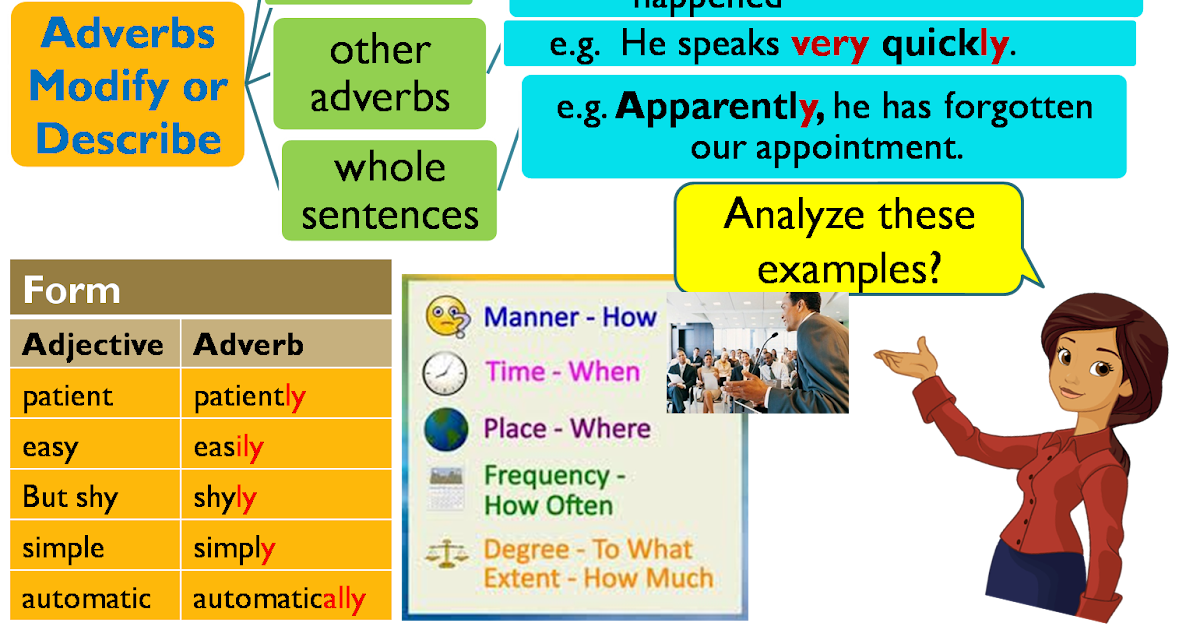

Imagine this: how would readers experience your voice if you used fewer adjectives and adverbs?

Here’s an example of text, sagging under adjectives and adverbs:

While quietly sitting at her wooden desk, she slowly formulated her thoughts and worked really hard to write her blog post. The next day she felt apprehensive and nervously hit publish. Would her audience be interested enough to read her content word-by-word?

To add energy to the text, the first step is to strip the content back to its bare bones:

While quietly sitting at her wooden desk, she slowly formulated her thoughts and worked really hard to write her blog post. The next day she felt apprehensive and nervously hit publish. Would her audience be interested enough to read her content word-by-word?

The stripped down version lacks nuance and color.

For hours, she sat at her desk. She wracked her brain, and slaved over her words to produce a blog post. And the next day? She hit publish with trepidation. Would her audience gobble up her words?

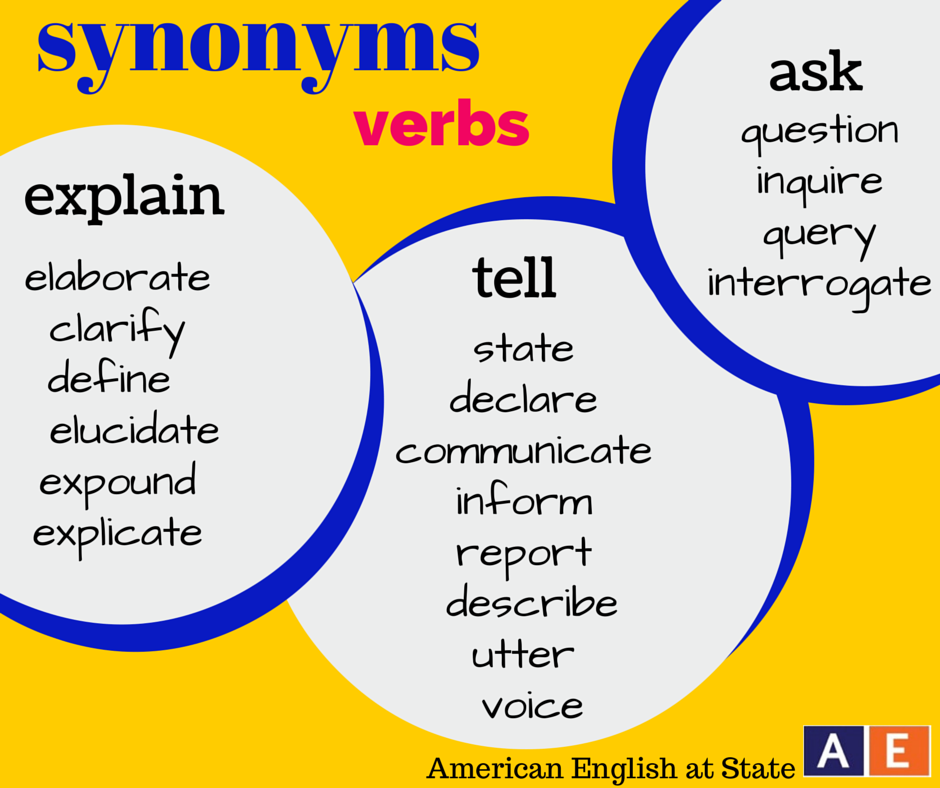

The thesaurus is your friend. Use a thesaurus to find more precise alternatives for weak verbs.

Your word choice shapes your voice

Finding your voice is about experimentation.

Write a first draft quickly using the words coming up into your mind.

Then, review your draft. In which sentences can you replace weak with strong verbs?

Which verbs can be more precise? Which verbs are sensory? Which verbs have a strong emotional connotation?

Play with your words. Have fun. And discover your voice.

How to Choose Words With Power and Pizzazz

- Discover 4 wordy rules for captivating your audience

- Learn how to fortify and energize your message

- Get examples that show you how to spice up your writing

A list of 351 strong verbs to inspire your writing

The list below is not exhaustive as many more strong verbs exist.

You can use a thesaurus to find other strong verbs, or keep an eye out for interesting verbs while reading.

To determine whether a verb is strong, ask yourself whether the verb has a sensory connotation. Does it make you hear, feel, smell, taste or see something? Does it paint a clear picture?

Onomatopoeic verbs

Onomatopoeic words express a sound, so they’re a sub segment of sensory verbs.

The word onomatopoeia comes from the Greek for making words—the sound has formed the word that represents it.

Examples:

To crack, to tap, to snap, to sputter, to knock, to boom, to clap, to bang, to drum, to squeal, to bump, to chatter, to twitter, to chirp, to clank, to click, to click-clack, to tip-tap, to jingle, to jangle, to rattle, to tinkle, to hush, to murmur, to plop, to pop, to fizz, to sizzle, to swoosh, to gargle, to sizzle, to hiss, to burp, to hiccup, to whack, to thumb, to crunch, to creak, to squeak, to flutter, to giggle, to tee-hee, to cackle, to honk, to hum, to meow, to woof, to munch, to shush, to screech, to slosh, to squish, to whirr, to gnaw

More examples of onomatopoeia on yourdictionary.

Sensory verbs

Sensory verbs are strong because they paint clear pictures in readers’ minds and make them feel something.

Examples:

To sparkle, to shine, to brighten, to wipe out, to muddle, to dazzle, to spark, to glow, to shimmer, to glimmer, to beam, to ripple, to tickle, to thrill, to explode, to burst, to guzzle, to gobble up, to breeze through, to drool, to spit, to roar, to thunder, to reverberate, to resonate, to rumble, to flavor, to smooth, to rub, to tremble, to whisper, to vibrate, to pulsate, to throb, to quiver, to buzz, to sip, to slurp, to slobber, to blemish, to applaud, to clash, to bounce, to blend, to shake, to savor, to tantalize, to tittilate, to pinch, to stroke, to brush, to bathe, to hose, to douse, to shower, to drench, to spray, to sprinkle, to trickle, to splash, to seep, to slide, to slump, to tumble, to nose-dive, to fly, to float, to clog, to swoop, to propel, to dig in, to dip, to surge, to wolf down, to shovel, to gulp down, to roll, to soar, to curl up, to unfold, to weave, to swipe, to tear, to polish, to pale, to vanish, to spin, to weave, to intertwine, to buckle down, to button up, to pierce, to stick to

More sensory words: How to Arouse the Magic of Sensory Words (Even in Business Writing!)

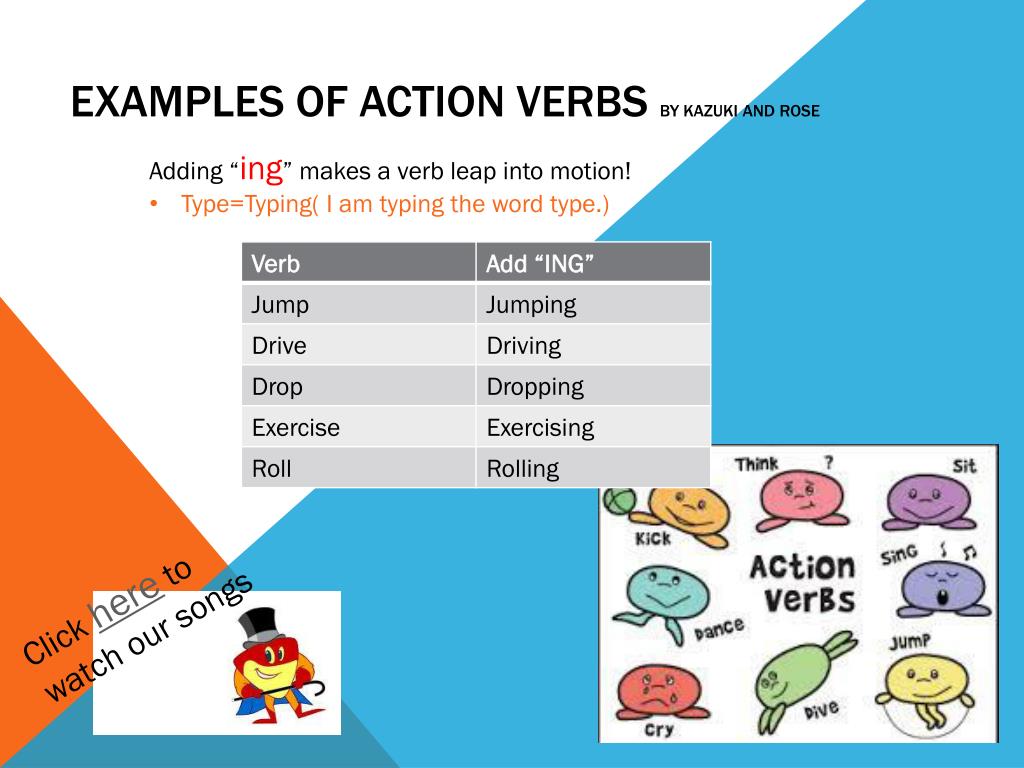

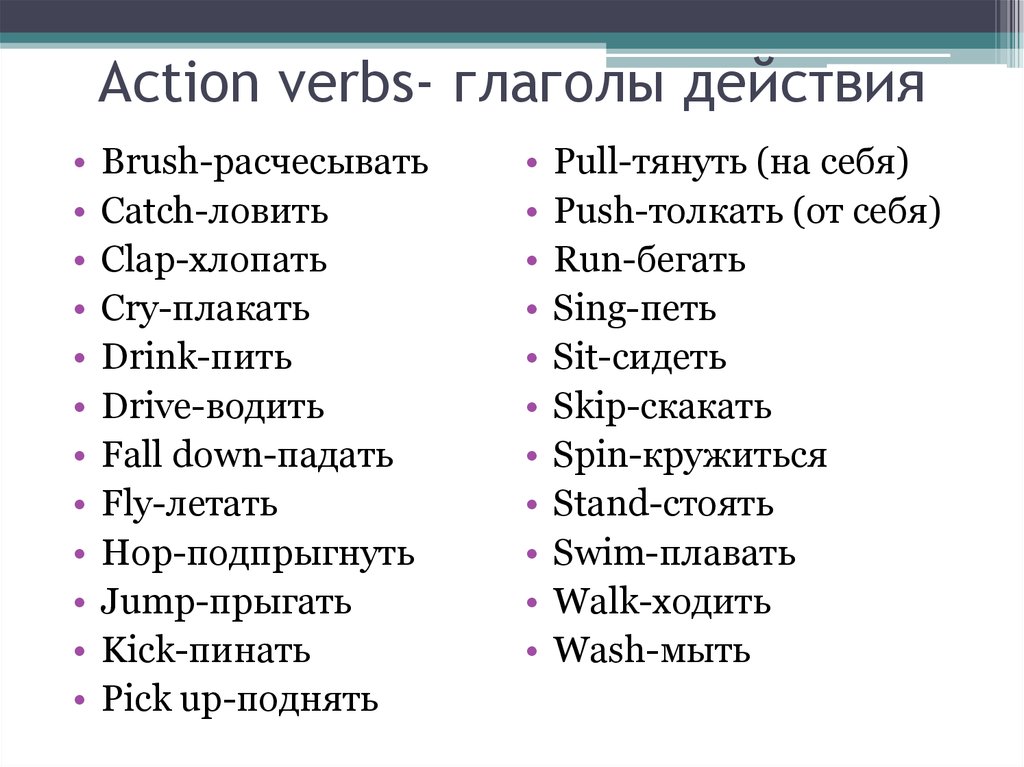

Strong action verbs—intransitive

Action verbs propel a sentence forward, keeping readers engaged.

Instead of using weaker words like walk or move, try to describe the movement more precisely so readers can imagine the movement.

Intransitive verbs can stand on their own, without an object. For instance, I walk is intransitive because there’s no object that is walked by me. I hit you is transitive—you are the object as you are hit by me.

Examples:

To stumble, to wobble, to swing, to lurch, to glide, to zip, to sail, to crash, to dive, to tiptoe, to pussyfoot, to duck, to flip-flop, to dilly-dally, to linger, to stall, to sway, to sink, to spurt, to hurry, to dash, to nip, to race, to whiz, to flit, to chew, to stroll, to sashay, to amble, to plod, to ramble, to loiter, to meander, to roam, to snake, to gallivant, to twist, to dance, to jig, to jive, to waltz, to tango, to swirl, to hop, to trip, to skip, to whirl, to gallop, to stride, to zoom, to trot, to dart, to sprint, to shoot, to leap

Strong action verbs—transitive

Below follow examples of words related to holding, pushing, or hitting something.

You can use these verbs for both concrete and abstract concepts. For instance, you can jump-start an engine or you can jump-start your career. You can squeeze a stress ball, or you can squeeze more to-do’s into your calendar. A cow regurgitates grass, and a blogger may regurgitate worn-out topics.

Examples:

To crank up, to flood, to snowball, to skyrocket, to catapult, to flick, to jump-start, to tackle, to grab, to grasp, to wrestle, to poke, to stir, to prod, to stab, to strike, to smash, to hit, to plunge, to drop, to dump, to drain, to squeeze, to topple, to ditch, to block, to muzzle, to electrify, to galvanize, to fire up, to ignite, to kindle, to whip up, to sharpen, to shock, to jolt, to beat, to regurgitate, to trigger, to pocket, to bat, to smack, to slap, to kick, to kick-start, to hammer, to nail, to club, to flog, to clutch, to hook, to cling, to grip

Negative emotional verbs

A verb like to fail has a strong negative connotation but doesn’t necessarily paint an unambiguous or vivid picture in a reader’s mind.

Below follow examples of more sensory verbs with negative connotations:

Examples:

To choke, to strangle, to smother, to gag, to suffocate, to throttle, to cry, to howl, to sob, to blubber, to scream, to groan, to moan, to fret, to fume, to bleed, to nag, to steal, to kidnap, to ransack, to loot, to pilfer, to plunder, to snitch, to puke, to vomit, to yelp, to bark, to growl, to grumble, to mutter, to spout, to suck, to scold, to plummet, to collapse, to skid, to agitate, to slave, to labor, to wreck, to ruin, to cripple, to devastate, to decimate, to trash, to shatter, to torpedo, to sabotage, to capsize, to maul, to crush, to slash, to bruise, to hijack

More emotional words: 172+ magical power words as proven by science

Positive emotional verbs

The verbs below paint strong positive imagery in your reader’s mind.

Your apple tree can blossom, and your blog can flourish. A magician might be spellbinding, but your blog posts can hypnotize readers, too.

Examples:

To flourish, to thrive, to bloom, to blossom, to mushroom, to smile, to grin, to cheer, to raise, to boost, to lift, to bolster, to invigorate, to energize, to excite, to enliven, to fortify, to hearten, to embolden, to animate, to arouse, to hypnotize, to spellbind, to sweep off one’s feet, to fall in love, to treasure, to unclog, to clarify, to disentangle, to liberate, to relieve, to release, to unshackle, to cuddle, to nestle, to huddle, to snuggle, to embrace, to hug, to kiss, to massage, to cradle, to enfold, to envelop, to sprout

Want to write with more power?

Click here to get the 22-page ebook How to Choose Words With Power and Pizzazz (it’s free!)

More Examples: 9+ Sentences With Strong Verbs

1. Strong verbs in Nora Seton’s kitchen

In her book The Kitchen Congregation, Nora Seton describes how she wanted her mother to spend more time with her when she was growing up:

I needed her there with me while I rolled, crawled, wobbled, ran, trampled, and grumbled on the red linoleum tiles of our kitchen floor.

It’s easy to picture the child rolling, crawling, wobbling etc on the kitchen floor? That’s how strong verbs help to paint strong imagery.

The following sentence is from the same book, describing the soaking of the grains:

All morning long the grains softened, gave in, soaked up, plumped, burst, spit their gluten and flavor into the dish.

Strong verbs don’t always come in long strings like that. Sometimes they pop up just here and there in a sentence. Here’s Seton musing in the kitchen:

I imagine a neutrino shower bombarding me, subatomic gunfire, zinging against the stainless steel in my hands and rocketing through the kitchen without trace.

2. Strong verbs on storytelling

Jane Alison uses 3 strong verbs in the title of her book about storytelling: Meander, Spiral Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative.

Alison suggests patterns are natural and uses strong verbs to describe such patterns:

We follow natural patterns without a thought: coiling a garden hose, stacking boxes, creating a wavering path when walking along the shore.

We invoke these patterns to describe motions in our minds, too: someone spirals into despair or compartmentalizes emotions, thoughts meander, heartbreak can be so great we feel we’ll explode.

3. Strong verbs on writing, a cat, and a praying mantis

In her book The Writing Life, Annie Dillard describes what writing is like:

This writing that you do, that so thrills you, that so rocks and exhilarates you, as if you were dancing next to the band, is barely audible to anyone else.

And in her book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Dillard uses strong verbs to describes how her cat wakes her up in the middle of the night:

He’d stick his skull under my nose and purr, stinking of urine and blood. Some nights he kneaded my bare chest with his front paws, powerfully, arching his back, as if sharpening his claws, or pummeling a mother for milk.

And she describes a praying mantis laying eggs:

It puffed like a concertina, it throbbed like a bellows; it roved, pumping, over the glistening, clabbered surface of the egg case testing and patting, thrusting and smoothing.

Can you picture all the movements?

4. Strong verbs in the desert

In his book The Secret Knowledge of Water, Craig Childs describes a thunderstorm in the desert:

It sounded like a block of marble cleaved open with a sledgehammer. The sky broke in two with thunder. Echoes pounded back, thrumming against my spine. Lightning shot to the southeast. The air exploded again. Lightning then fell all around, snagging on the higher terrain. Scraps of lightning showed from behind rock towers. I counted the canyons by how many echoes of thunder were returned. Four pulses of thunder: four canyons. Then I heard the tapping. Rain began to fall. Another bolt of lightning. The rain increased, dabbing my face, making the sound of bean-filled rattles. I could hear it up on the cliffs, rain sheeting against rock.

In the above paragraph, the strong verbs describe a multi-sensory experience. There’s movement (cleave open, break in two, explode), sound (pound, thrum, shoot, tap), sight (sheet), and touch (dab).

5. Strong verbs describing an escape on horseback

In his book All the Pretty Horses, Cormac McCarthy describes Rawlins, Blevins, and John Grady escaping on horseback:

The horse skittered past Rawlins sideways, Blevins clinging to the animal’s mane and snatching at his hat. The dogs swarmed wildly over the road and Rawlins’ horse stood and twisted and shook its head and the big bay turned a complete circle and there were three pistol shots from somewhere in the dark all evenly spaced that went pop pop pop. John Grady put the heels of his boots to his horse and leaned low in the saddle and he and Rawlins went pounding up the road. Blevins passed them both, his pale knees clutching the horse and his shirttail flying.

Thanks to the strong verbs, you can see the boys escaping, almost feel the motion, and hear the noise of the hooves pounding up the road. The strong verbs include: skitter, cling, swarm, twist, shake, pound, clutch, and fly.

Note: This post was originally published on 14 February 2016; an expanded version was published on 12 June 2019; last update on 17 June 2022.

Strong Verbs List (your ultimate guide for more captivating writing)

Why should it matter so much whether your verbs are strong or weak?

And how do you even know if you’re using weak verbs?

If you know the answer to the question, “What is a verb?” and if you enjoy reading, it won’t take long to answer the bigger question of how to replace weak verbs with strong ones.

Because you know the purpose of the verb isn’t just to give you a pencil tracing of what’s going on.

It’s supposed to show you as much as possible with an economy of words.

This is why adverbs get so little love from writers nowadays.

They try to compensate for the inadequacies of weak verbs, but all they end up doing is making the sentence harder to read (without cringing).

Who knew there were two types of verbs, anyway, though?

Don’t all verbs basically do the same thing?

Well, yes and no.

Weak verbs can tell your reader what’s happening, but only strong verbs can catapult them right into the action.

Want to know how? Of course, you do!

What writer doesn’t want to master the art of captivating their readers with strong, evocative language?

And to help you do this, we’ve included a strong verbs list, which you can draw from to turn a basic narration into a full-color IMAX in-house movie.

But how do you tell a weak verb from a strong one?

What’s In This Article?

[show]

What Are Strong Verbs

Strong verbs are the best verbs for a specific context because they do the following:

They stand out as both unusual (or unexpected) and appropriate.

They paint a specific picture of what’s going on — creating a stronger visual.

They evoke an emotional response in the reader.

The strongest verb is the one that communicates exactly what someone is doing and how they are doing it — without any need for an adverb.

By contrast, the weakest verb is the easiest one to use, and it communicates as little as possible while giving you the basic idea of what’s going on.

Sometimes, a weak verb is the one to use, but if all or most of your verbs are weak, your writing will be dull and lifeless. It won’t paint a clear picture, and it won’t evoke an emotional response.

And it’s way too easy to put down.

Strong Verbs Vs. Weak Verbs

While strong verbs are specific, weak verbs are general.

For example, you can say someone ran down the hallway, and that gives you the basic idea of what’s happening, but it’s also bland.

But if you say he bolted down the hallway, you communicate more of the urgency or even panic behind it.

You show the reader some of the emotion behind the action. Weak or “basic” verbs don’t do that.

When you use weak verbs like “ran” or “walked” or “smiled,” it’s tempting to use an adverb or a clichéd adverbial phrase to make the verb sound more interesting by telling the reader how the subject is doing something.

Strong verbs SHOW. Weak verbs — and their supporting adverbs — TELL.

He ran like a cheetah.

He ran frantically.

She smiled

She smiled from ear to ear.

The adverbs don’t really make the verb more compelling. They add detail but without making the action feel more real.

The character running frantically down the hallway is as much a stick figure as the one running like a cheetah. But the character bolting down the hallway makes the reader wonder what might be pursuing him or what’s at stake.

Or if the reader already knows the why, the word “bolted” is more satisfying than simply “ran.”

As the more appropriate verb, it feels more like the appropriate response to the danger at hand, and it leads the reader deeper into the story.

Strong verbs paint clearer and more vivid images in the reader’s mind, making them care more about what will happen next. They add an extra dimension to the character taking action.

How easy is it, though, to replace your weak verbs with strong ones?

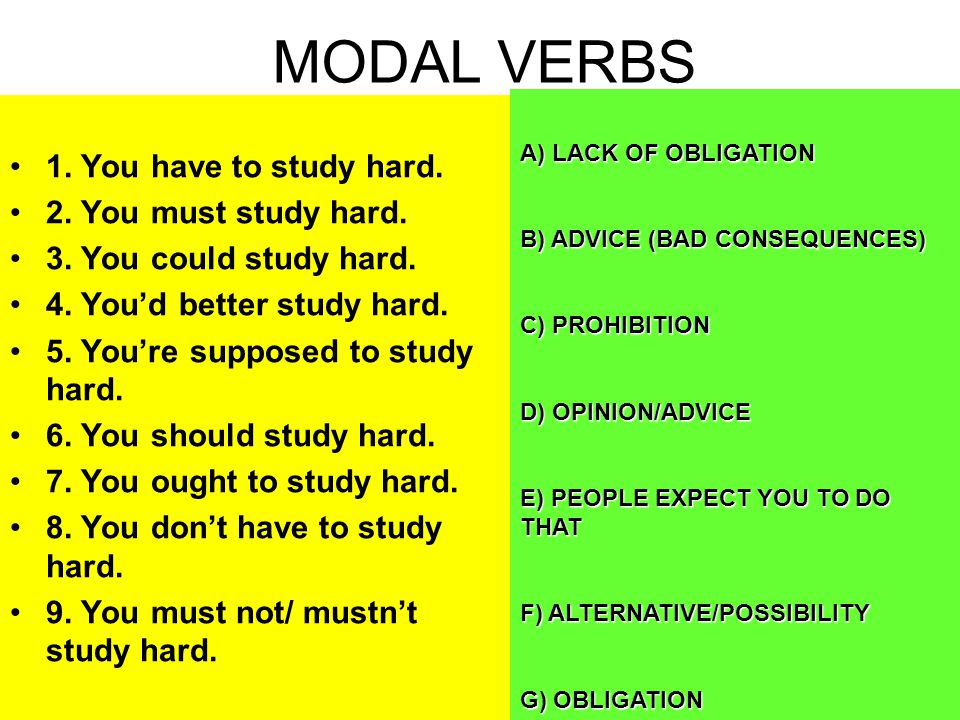

Replacing To Be Verbs

Weak verbs are everywhere because they’re easy to use.

If there was a supermarket for verbs, the weak ones would be at eye-level and right across from the ice cream freezer. We’re only human.

The weakest of the weak verbs are “to be” verbs (also called simply “be verbs”). They’re not evil incarnate, though. and there are times when they’re the best words to use.

If you can say the same thing with a strong verb — in a way that doesn’t sound like you’re forcing it in there — go with it. But don’t try to make every verb a strong one.

No one wants to read something that sounds like the writer swallowed a thesaurus and chased it with some ipecac, but try to mix it up as much as you can.

When your reader’s attention is at stake, it’s worth it to find verbs that will get the response you want.

It’s also worth changing combinations like the following to eliminate the extra “to be” verb:

From “I was wanting“ to “I wanted”

From “He’s already been waiting” to “He’s already waited.

From “She was being sad“ to “She was sad.”

To Be Verbs List

These verbs are used alone and as part of compound verbs like “are used” and “has been scared.”

If you’re yawning right now, you’re not alone. While there’s definitely a place for “to be verbs,” don’t let them do all the work.

Don’t beat yourself up, though, if you look through something you’ve written and you find that most of your verbs (or even all of them) are weak verbs. As I mentioned earlier, they’re low-hanging fruit. We all use them.

But when you’re more conscious of the verbs you choose, chances are your readers will be more conscious, too.

If you’re not already familiar with the “to be” verbs, here’s a list:

Should

The Ultimate Strong Verbs List

We’ve broken the following list of strong verbs into subsets to help you more quickly find the strong verb with the exact quality you want — from vivid to forceful to fun.

Verbs do have a tone, and even verbs that mean generally the same thing won’t work equally well in the same context.

If your character is having a nighttime phone conversation within earshot of her sleeping captors, you’ll want to avoid dialogue tags with verbs like “broadcasted,” “blabbered,” or “announced.”

The thesaurus does open the door to a whole new universe of more evocative verbs, though, and the lists below give you a taste.

Part of what makes the verb appropriate, though, is the sound it makes and how it affects the rhythm of your sentence.

So, read the word aloud in the context of your sentence and make sure it reads easily, sounds like it belongs there, and creates the right visual effect.

The same verb can belong to multiple categories, based on the impact you want to make and on the mood you’re in as you read this.

Take a slow read through the lists that follow and take note of the ones that stand out for you.

Power Verbs

If you’re rereading one of your sentences and feeling the need for a more powerful verb — one that grabs the reader’s attention and leaves them in no doubt as to your meaning — see if one of the following verbs are a better fit.

Maybe they’ll at least get your mind so in tune with powerful verbs that you have an easier time thinking of just the right one.

Advance

Amplify

Attack

Broadcast

Charge

Clutch

Command

Devour

Engulf

Explode

Ignite

Plunge

Scorch

Shatter

Wrestle

d

More Related Articles

15 Common Grammar Mistakes That Kill Your Writing Credibility

31 Ridiculously Simple Tips For Writing Your Next Book

Grammarly Review: Is This the Best Grammar Checker?

Vivid Verbs

Some verbs just don’t create a vivid enough picture for your reader. You want a verb with visuals that pop in your reader’s mind.

The following should give you some ideas.

Batter

Catapult

Collide

Dismantle

Expose

Glitter

Hobble

Intertwine

Jostle

Launch

Pinpoint

Poison

Retreat

Scratch

Scrawl

Sizzle

Starve

Struggle

Forceful Verbs

If you’re looking for a verb with a strong and undeniable presence — one that gets the message across with a one-two punch and without apologies — consider the verbs in this list.

Capture

Decimate

Deviate

Demolish

Devastate

Dominate

Extract

Oppress

Revitalize

Terrorize

Wrench

Interesting Verbs

Maybe you just want a verb that sounds more interesting than your original choice — but without sounding forced or flowery.

You don’t want purple prose, but you do want to keep your reader interested. So, mix it up with one of the dazzling verbs below.

Discover

Ensnare

Envelop

Glisten

Illuminate

Intuit

Journey

Mystify

Perceive

Position

Realize

Refashion

Reveal

Reverberate

Transfigure

Transform

Travel

Uncover

Unearth

Withdraw

Fun Verbs

Some verbs are just more fun than others. It’s not a competition; it’s just how it is.

Some verbs get all the oohs and ahhs but none of the laughs. They’re cool with it. They know their place.

The following should give you some ideas.

Eyeball

Garble

Gobble

Prickle

Tattle

Tussle

Trudge

Wrangle

Descriptive Verbs

Some verbs just do a better job of describing how a character is doing something.

It paints a clearer picture, so the reader is better able to visualize what’s going on.

These might not be the most vivid verbs, but they do show you more detail than your average “basic” verb.

Balloon

Clutch

Downlaod

Eavesdrop

Escort

Expand

Explore

Extract

Hobble

Recite

Saunter

Scamper

Scrape

Shepherd

Snowball

Sparkle

Sprinkle

Stroll

Stummble

Survey

Toddle

Untangle

Unveil

Cooler Ways to Say “Said”

You’ll find some of these in the other lists, but it makes sense to gather up other ways to say “said” into a list of their own.

Sometimes, “said” is just fine. But if you’re using a lot of dialogue tags, and you’d like to show a little more of how your character is saying something (with making things awkward), a list of strong “said” verbs will come in mighty handy.

Don’t overdo them, though. And if you can indicate who’s speaking without using a dialogue tag at all, so much the better.

The following verbs are also helpful in other contexts where you might use the word “said.”

Side Note: I’m omitting the word “exclaimed” on purpose; the word is overused and pure torture to read.

Advertised

Affirmed

Alleged

Announced

Articulated

Asserted

Avowed

Bellowed

Blabbered

Blurted (out)

Broadcasted

Breathed

Chanted

Chirped

Commented

Crooned

Declared

Drawled

Enunciated

Gasped

Growled

Gushed

Hinted

Imparted

Implied

Instructed

Lisped

Mumbled

Murmured

Paraphrased

Piped up (with)

Pontificated

Postulated

Proclaimed

Purred

Put into words

Rattled off

Recited

Reeled off

Remarked

Repeated

Rephrased

Reported

Restated

Roared

Shared

Shouted

Snarled

Spluttered

Spouted

Stated

Stuttered

Suggested

Summarized

Vented

Voiced

Wailed

Whimpered

Whined

Whispered

Strong Action Verbs

With strong action verbs, you can almost physically feel their impact.

- Annihilate

- Bound

- Bulldoze

- Cream

- Eviscerate

- Gallop

- Hammer

- Hurl

- Jog

- Lob

- Mope

- Nail

- Pound

- Pummel

- Ram

- Scrabble

- Shred

- Slice

- Smack

- Spark

- Sprint

- Stomp

- Trot

- Whack

- Zip

Was this list of strong verbs helpful?

Now that you have a fair sampling of strong verbs to choose from, we hope you keep this post handy, and that it serves you well.

Remember that it’s not so much a question of good verbs vs. bad verbs.

The weakness of a “to be” verb or a general verb doesn’t make it bad; it just makes it less communicative. It has less of an impact than a strong verb.

But as we mentioned before, sometimes a weak verb is honestly the best fit.

I don’t know any. And that’s okay. Sometimes, phrases using weak verbs — like “Need more coffee” — say everything you need to say. So, no verb shaming allowed.

May your ingenuity and compassion influence everything you do today.

14 pairs of verbs in which you make mistakes

June 19, 2019 Education

Share

0

Due to homonymous roots (similar in sound), even those who know about the difference between two words can automatically make a mistake. Therefore, even if most of the lexemes do not cause you any difficulties, it will not be superfluous to check yourself and remember something.

1. Illuminate and consecrate

Every year during the Easter period, an error in the use of these words occurs at every turn. By ear, there is not much difference, but in terms of meaning, the verbs do not mean the same thing.

2. Develop and flutter

Verbs whose meaning changes depending on the vowel used in them. You can check it by finding a single-root test word with a suitable stress. “To develop” means the same as to improve, and is easily verified by the lexeme “development”. «Fluff» means «flutter in the wind, sway in the air.» You can check with the word «veyat».

3. Sit and go gray

Another stumbling block among verbs, although in reality everything is simple. You can sit on something: on a chair, sofa, stool, and so on. And graying will turn out only from old age or nervous strain.

4. Hangs and weighs

Roots in these words are often the cause of error.

5. Discharge and Discharge

These verbs sound the same, which only adds to the confusion. In order not to make a mistake, you need to know the context in which they are used. You can thin out something, such as seedlings or bushes. That is, make them less frequent.

Unloading the situation or some kind of weapon. The single-root word «discharge» will help to check the spelling. In principle, you can also discharge someone, for example, a doll. It is a colloquial synonym for the word «dress up».

6. Reconcile and try on

You won’t make a mistake if you know the sense in which the word is used. You can reconcile enemies, because the root: -peace-. And they try on clothes, from the words «measure», «measure».

7. To sing and drink down

If we are talking about starting to sing, then we will write “to sing”. If you need to take a pill, then the word must be written through “and” — from the lexeme “drink”.

8. To belittle and beg

A fairly complex pair of verbs, errors in them are not uncommon. To belittle means to belittle, diminish, humiliate. We have the root -small- and the same-root words «little» and «small». Usage example: «Detract from one’s self-respect.» And to beg has the meaning «to ask», the root — they say — and the same root «to pray».

9. Live and chew

This couple is easy enough to deal with. You can live somewhere: in a cottage, in a house, in a country house, and so on. One root word is «live». And you can chew food. You will not make an annoying mistake if you start from the context.

10. Open and boil

It seems that it is difficult to make a mistake here, but this happens. Because we are dealing with homophone words.

11. Lick and climb

It also depends on the context: to climb somewhere, that is, to climb, but you can lick something, for example, a wound.

12. Glow and stick

The word «glow» is often misspelled, and some people write the non-existent «prick». The lexeme comes from the word «incandescence» and means to heat something up to a certain temperature. And you can chop wood or use this word in the meaning of “string an object on something”.

13. Write and write

They sound different, and you are unlikely to make a mistake in a conversation. But in a letter, it can appear. Let’s understand with examples. The “write” form is an appeal that encourages action. In other words, imperative. For example: «Write on this topic more often, it is interesting.» And “write” is a plural and second person verb.

14. Equate and equalize

Most do not even see the difference between these paronymic verbs, but there is one. The lexeme «to equalize» means «to make something equal, to equalize». For example: «I want to equalize our chances of success.» There is also a second meaning — «to compare, compare». But in this context, this word is outdated and will only be found in literature or dictionaries. But to equalize means to make even, level. Example: «I want to raze this place to the ground.» By the way, “raze to the ground” is a set expression that means to destroy something to the ground.

Read also 😞✍️🧐

- 20 expressions in which everyone around makes mistakes

- 26 words whose plural form is difficult

- 20 words that even literate people spell incorrectly

Good and bad dictionaries: the verbs “Soviet” and “non-Soviet”

In Soviet times, Russian language dictionaries were both simpler and more complicated than they are now.

Now the major bookstores offer so many dictionaries that it’s dizzying! There are even highly specialized ones dedicated to profanity. But which of these books can be trusted? Suffice it to say that the stress in the same word in different editions can be different. So what kind of dictionaries should be in the house of a person who cares about the culture of his speech?

Yulia Safonova, a member of the editorial board of the GRAMOTA.RU portal, recommends following the following rules when choosing a dictionary: “A person who cares about the culture of his speech must necessarily have a little-known, but in my opinion the best dictionary, the author of which is Natalya Alexandrovna Yeskova. It is called «Concise Dictionary of Grammar Difficulties». Let the name not confuse you, because there are not only grammatical difficulties, although they exist, but, in fact, this is an orthoepic dictionary, and in the orthoepic dictionary, as a rule, all the norms of stress and pronunciation are indicated.

“The dictionary was first published back then by the Soviet publishing house Russkiy Yazyk. It has now been reprinted several times. I don’t know what this publishing house is called now, but you can just remember the name and the author — Natalya Aleksandrovna Eskova. A rather rare surname, ”explains Yulia Safonova and continues the story:“ This dictionary has not had time to become outdated, because Natalya Alexandrovna has been working on a large orthoepic dictionary for a long time, edited by Ruben Ivanovich Avanesov. This dictionary is traditionally used by philologists and everyone associated with public speech — announcers, artists. I don’t know a better dictionary than her today. He is very small. Because when you have a thick dictionary, it scares you: sometimes people cannot interpret the dictionary entry correctly. And that’s great art.»

Yulia Safonova believes that the art of interpreting a dictionary entry — the art of using a dictionary — is little taught at school and almost never taught at higher educational institutions: “The dictionary of Natalia Alexandrovna Yeskova successfully combines such things as indicating the correct grammar, gender, correct administration — and some other tasks.

You say the dictionary is small. This has its advantages, of course, but there are also disadvantages. So, many words can not be found in it. Do you need more publications then?

And you don’t need all the words. You only need those words where there are difficulties. In the word «mother» you will not have any questions about how to pronounce it. Therefore, the first thing you need to determine is why you need a dictionary. If you want to know how all words are spelled, then today you can also recommend only one dictionary — this is a dictionary edited by Professor Vladimir Vladimirovich Lopatin. It is called «Russian Spelling Dictionary».

Yes, people, even those who are far from linguistics, know that these are big names.

These are big names, of course.

And the censors thought that “owls.” is it short for the word «Soviet»?

Anyway, such questions were asked, or some examples were asked to be corrected. According to the rules in the dictionary entry, if in your example the so-called “black word” is repeated, that is, the word that heads the dictionary entry, say, “capless cap”, if in your example in the same form, that is, in the usual form of the nominative or accusative case, it is reduced to the first letter. The censor’s question was: «We need to replace the example of «sailor b.», what might people think? What might people think? This is a dictionary.

According to Yulia Safonova, there are dictionaries that should be blacklisted: “I regularly see a spelling dictionary for sale, the author of which is Sergei Ivanovich Ozhegov.

We invoke these patterns to describe motions in our minds, too: someone spirals into despair or compartmentalizes emotions, thoughts meander, heartbreak can be so great we feel we’ll explode.

We invoke these patterns to describe motions in our minds, too: someone spirals into despair or compartmentalizes emotions, thoughts meander, heartbreak can be so great we feel we’ll explode.